You have no items in your cart. Want to get some nice things?

Go shopping

Psychoanalyst Adams Phillips writes, “Our lives are defined by loss”. For when we lose things they disappear, yet we remember, recall, and, in turn, we become inhabited by that which is no longer there. Lost things live on in us, vacillating between absence and presence.

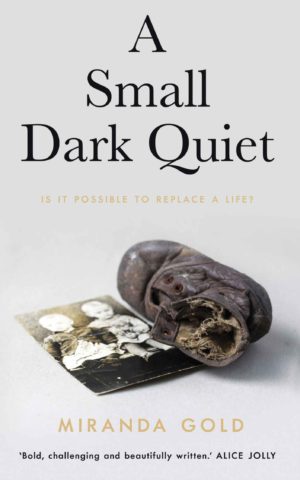

Set in a crumbling post-WW2 London, A Small Dark Quiet by Miranda Gold is a book about loss, a delicate, haunting meditation on a generation both engulfed and shattered by war. The Allies have been victorious, and everyone should be celebrating, but inside the tiny house in Llanvanor Road, Sylvie has lost one of her twin sons at birth; she seems to be losing her mind. Two years later, Sylvie and her husband Gerald adopt little Arthur, a concentration-camp survivor, as a replacement for their dead baby. The child has been dispossessed of his own identity, is given the name of the deceased twin. He is “someone else’s little someone”. The father, Gerald, has also lost, or is trying to lose, his family’s Jewish identity. The book translates intelligently the unshakable fear Gerald still feels of being Jewish in Europe. His hands shake relentlessly and he is suffering from what we would now diagnose as PTSD. The war is over, yet things for the family will never be the same again. It is, Gerald believes, “tabulae rasae … records had been scattered, blanks left pending…”

A Small Dark Quiet is also the story of how we fill these blanks, how we live with the real and metaphysical horrifying gaps, described by Edna St Vincent Millay as the “hole in the world, which I find myself constantly walking around in the daytime, and falling in at night.” “Let’s find her smile. Let’s find her smile,” Gerald repeats cruelly to Sylvie in their kitchen, trying to recover, resuscitate, the Sylvie he once knew. “My Sylvie had a nice smile,” he says.

Interweaving scenes from 1950s and 1960s, darting between Freud’s mourning and melancholia, as the book advances, author Miranda Gold reveals the stories the characters have told themselves to make sense of their trauma. Each of them tries to deal with their past selves, those which they have relentlessly tried to get rid of, as Roxanne Gay describes, “I buried the girl I had been because she ran into all kinds of trouble. I tried to erase every memory of her, but she is still there, somewhere.” We follow Arthur through his own attempt to build an adult life, to understand where he belongs. We meet other characters living with “small dark quiets”: a Polish caretaker with a number tattooed on his arm. Lydia, Arthur’s lover, who is repairing her own past by playacting the role of her previous employer, Mrs Simons. Lydia was the Simons’ nanny, and has stolen the family’s two dolls, and now, grotesquely, pretends they are her children.

In the novel, the strongest, most haunting image of loss and its replacement is the infant Sylvie fabricates from twigs and minuscule buds of white flowers to replace (or make living) her dead baby. This “twig baby” encapsulates “the story of the other little Arthur that Arthur never was…” In the novel, Sylvie believes her baby is buried in the park and visits the grave every Thursday, trying to find “a grave that would keep him.” In one exquisitely painful scene, she takes Arthur to the park; they dig in the soil and grass, hands muddy, trying to find the baby. Gold’s visceral image is macabre and tender, frightening and soft. Sylvie clutches a bundle of twigs, placing her hope, her longing in withered ivory petals.

In A Small Dark Quiet, Miranda Gold’s force is her concentration on ordinary darkness, the banal, yet ruthless effects of war and trauma on the everyday. In keeping with this focus on the intimate life of a family, the book takes place in restricted locations: Llanvanor Road, the park, Arthur’s workplace, the squalid room he rents when he seeks independence and meets the unstable Sylvie. Yet, while the cast and places of the book are clearly identified, the writing darts endlessly back and forth in time. Whilst this is in keeping with the effects of trauma, which exists outside of time, the latter part of the book can be confusing to follow.

Overall, however, A Small Dark Quiet is a highly perceptive, beautifully crafted, lyrical book, highlighting aspects of the trauma of WW2 often ignored. Books like this must be written and read, for as the Nobel laureate Elie Wiesel warned years ago, “to forget a holocaust is to kill twice.” This is a loss we cannot neglect.

A Small Dark Quiet is published by Unbound.

About Susanna Crossman

Susanna Crossman is an Anglo-French writer, winner of the 2019 LoveReading Very Short Story Award. Nominated for Best of The Net (2018) for her non-fiction, her fiction has also been short-listed for the Bristol Prize and Glimmertrain. She has recent/upcoming work in Neue Rundschau, S. Fischer (translated into German), Repeater Books, ZenoPress, The Creative Review, 3:AM Journal, The Arsonista, Litro and elsewhere. Co-author of the French roman, Hôpital Le Dessous des Cartes, she regularly collaborates on international hybrid arts projects, currently the multi-lingual prose film, 360° of Morning. She is represented by Craig Literary, NY.

- Web |

- More Posts(2)

Great review!