You have no items in your cart. Want to get some nice things?

Go shopping-

-

-

-

-

-

-

-

-

-

-

-

-

-

-

-

-

-

-

-

-

-

-

-

-

-

-

-

-

-

-

-

-

-

-

-

-

-

-

-

-

-

-

-

-

-

-

-

-

-

-

-

-

-

-

-

-

-

-

-

-

-

-

-

-

-

-

-

-

-

-

-

-

-

-

-

-

-

-

-

-

-

-

-

-

-

-

-

-

-

-

-

-

-

-

-

-

-

-

-

-

-

-

-

-

-

-

-

-

-

-

-

-

-

-

-

-

-

-

-

-

-

-

-

-

-

-

-

-

-

-

-

-

-

-

-

-

-

-

-

-

-

-

-

-

-

-

-

-

-

-

-

-

-

-

-

-

-

-

-

-

-

-

-

-

-

-

-

-

-

-

-

-

-

-

-

-

-

-

-

-

-

-

-

-

-

-

-

-

-

-

-

-

-

-

-

-

-

-

-

-

-

-

-

-

-

-

-

-

-

-

-

-

-

-

-

-

-

-

-

-

-

-

-

-

-

-

-

-

-

-

-

-

-

-

-

-

-

-

-

-

-

-

-

-

-

-

-

-

-

-

-

-

-

-

-

-

-

-

-

-

-

-

-

-

-

-

-

-

-

-

-

-

-

-

-

-

-

-

-

-

-

-

-

-

-

-

-

-

-

-

-

-

-

-

-

-

-

-

-

-

-

-

-

-

-

-

-

-

-

-

-

-

-

-

-

-

-

-

-

-

-

-

-

-

-

-

-

-

-

-

-

-

-

-

-

-

-

-

-

-

-

-

-

-

-

Uncategorized

Cinnamon rolls and racists

-

-

-

-

-

-

-

-

-

-

-

-

-

-

-

In a world where AI is reshaping industries left and right, it’s no surprise that the literary world is grappling with its own AI dilemmas. NaNoWriMo, the nonprofit that runs the famed month-long novel-writing challenge, has found itself in hot water over its stance on AI. Rather than outright condemning the use of AI-generated content in their challenge, they took a neutral stance, sparking a heated debate among writers who view this as a slippery slope for the craft of writing.

As someone who thrives on innovation and pushing boundaries, I believe AI has its place in the creative process—but let’s be clear, it needs to be tagged. If AI is used to assist with writing, it should be labeled as AI-generated, allowing transparency and clarity. Creators have every right to experiment with tools that help them, but the work still needs to be distinguished from purely human-crafted stories. It’s about protecting both the craft and the creative process.

NaNoWriMo’s position—that condemning AI would be “classist and ableist”—brings up valid concerns about accessibility, but I think the issue here isn’t whether AI should be allowed, but rather how it’s used and how clearly it’s defined. Labeling AI-generated work gives readers a choice and preserves the integrity of the human creative experience.

Prominent writers like Daniel José Older, who stepped down from the organization, see this as a fundamental threat to writing. The response has been swift, with both writers and sponsors pulling out in protest. But here’s where I stand: AI can be part of the equation, but not without transparency. Tagging AI-generated content ensures that the playing field stays level and that the essence of writing—human creativity—isn’t quietly sidelined.

Let’s embrace innovation, sure. But let’s also respect the craft and keep the lines clear.

These books, once banned or challenged for their bold themes, remind us of the power of literature to inspire thought, challenge norms, and spark important conversations. From dystopian classics like “1984” to the emotional depths of “Beloved”, each of these works has been targeted for censorship, yet they continue to shape our understanding of the world around us.

As we enter the autumn season, there’s no better time to explore these thought-provoking stories. Whether you’re revisiting a familiar favorite or diving into one for the first time, these books invite you to reflect on the importance of free expression and the ongoing fight against censorship. Let them challenge and comfort you as the days grow shorter.

I’m sure many of you have at least one of these titles sitting on your bookshelf, waiting to be read. This autumn, why not pick it up and explore the ideas that have made these works both controversial and essential? Whether it’s revisiting a classic like “Fahrenheit 451” or finally getting around to “The Handmaid’s Tale,” these books remind us of the power of literature to challenge the status quo.

Which book will you pick up this autumn?

” The Handmaid’s Tale” by Margaret Atwood

- Reason for Ban: Challenged for depictions of sexuality, religious criticism, and its portrayal of a totalitarian regime.

“1984” by George Orwell

- Reason for Ban: Often challenged for its political themes, particularly its criticism of totalitarianism, which has led to it being banned in various countries at different times.

“Fahrenheit 451” by Ray Bradbury

- Reason for Ban: Ironically, a book about censorship has been banned for its portrayal of book burning and the discussion of controversial ideas, including language considered inappropriate.

“Beloved” by Toni Morrison

- Reason for Ban: Frequently challenged for its depiction of violence, sexual content, and themes surrounding slavery and racism.

“The Bluest Eye” by Toni Morrison

- Reason for Ban: Often banned for its explicit descriptions of rape, incest, and racism, which some argue make it inappropriate for certain audiences.

“The Giver” by Lois Lowry

- Reason for Ban: Challenged for its depiction of euthanasia, emotional depth, and themes of control and individuality, which some consider disturbing for young readers.

“Slaughterhouse-Five” by Kurt Vonnegut

- Reason for Ban: Often banned due to its depictions of war, violence, and the use of profanity, as well as its exploration of existential themes.

“Brave New World” by Aldous Huxley

- Reason for Ban: Challenged for its portrayal of a dystopian society obsessed with pleasure and control, with criticisms over sexual content, drug use, and its critique of religion.

As the 2024 U.S. elections approach, the issue of book banning has evolved from a cultural flashpoint into a battleground for democracy. With censorship at an all-time high, particularly targeting books that explore race, gender, and identity, those fighting for intellectual freedom face mounting challenges. Across the country, far-right political movements, often backed by conservative leaders, have sought to remove books from schools and public libraries under the guise of protecting children from “inappropriate” content. Yet, this censorship is being met with strong opposition. Polls consistently show that a majority of Americans—across party lines—reject these bans, recognizing them as an authoritarian attempt to control public discourse and limit access to knowledge.

Recent elections have further emphasized this shift, as voters rejected candidates running on pro-book-ban platforms, particularly in states like Florida where such policies were heavily promoted. Still, the battle is far from over. As book bans become a key issue in the 2024 elections, it’s crucial to highlight those on the frontlines. I recently spoke with Jennie Pu, Director of the Hoboken Public Library, a staunch advocate against censorship. Our conversation explored the rise of the Book Sanctuary movement and how communities can resist these threats to free expression. Now, more than ever, we must stand up for the right to read, especially in a political climate where censorship is used as a tool of control.

EA: “With book banning at the highest levels in U.S. history, what factors do you think are driving this unprecedented wave of censorship?”

We are living in an unprecedented time of division in our country. This divisiveness has spurred this wave of censorship, a rise in vitriolic attacks, and suppression of diversity of thought. According to the American Library Association (ALA), last year alone saw a record-breaking 1,269 efforts to censor books nationwide, compared to 300-400 reports a year of efforts to ban books in previous years. These are definitely challenging times for our communities, readers, and specifically librarians. But I’m hopeful, because what we’re seeing is most Americans actually oppose censorship, and they love their libraries. Here in New Jersey, more and more libraries are becoming book sanctuaries, because book sanctuaries reflect what most Americans value and believe: free, open access to information and knowledge.

EA: “How has the rise in book banning changed the role of libraries in communities across America?”

The rise of book banning has certainly put libraries in the spotlight. Some aspects of work that we’ve done for decades, such as collection development, have come under new scrutiny. Our role hasn’t changed: libraries are community anchors, and we serve everyone. What has changed is our work has taken on new urgency, and we are doing more ongoing and proactive work to protect and safeguard the freedom to read. At Hoboken Public Library, we have done this by being the first in New Jersey to make the library a book sanctuary – a place that welcomes, embraces, and celebrates all stories and people.

Book Banning and the U.S. Election

EA:“As we approach the upcoming election, what role do you foresee book banning playing in the political landscape?”

Libraries are, and always have been, non-partisan. Book banning is used as a tool to advance an extreme, partisan political agenda, but it’s manufactured outrage and does not reflect the sentiments of most Americans. Polls after polls show that 70% of Americans oppose book bans. The freedom to read and the right of free speech is our constitutional right, as stated in the First Amendment, and most people will fight to preserve that.

EA: “Do you think book banning will become a key issue for voters, and how should communities prepare for potential political pressure on their libraries?”

We’re already hearing it mentioned in certain campaigns, so it’s already politicized. But we know from national surveys that the vast majority of Americans do not support book bans. So it’s up to each of us to show support for local libraries and that starts with our own communities. Visit your library, use your library and tell the folks who are in elected office how much the library means to you. Your voice is your superpower.

Community Involvement and Activism

EA: “For those who want to get involved, what are some practical steps they can take to support intellectual freedom in their own communities?”

There are definitely ways to get involved locally. First: go visit your local library. Talk to the library staff: many of them live in the community. Ask them about any challenges they’ve experienced, and ask them to tell or show you all the creative ways they’re doing to support and defend intellectual freedom. Second: read a banned book, and talk about it with friends and family. Many still aren’t aware that censorship is a real issue and take their civil liberties for granted. Read local news, attend board of ed meetings, drop in at a local community meeting, there’s lots of ways to get involved.

EA: “You’ve mentioned something as simple as reading a banned book and discussing it with others. How can small actions like this make a difference in the larger movement?”

The book sanctuary movement here in New Jersey is truly grassroots and started with small actions. I knew that the Chicago Public Library and the City of Chicago originated the book sanctuary idea back in 2022, but it took over a year for us to bring that here and figure out how to make it work for our community.

In August 2023 Hoboken Public Library became the first book sanctuary in the state; the City of Hoboken joined us 2 weeks later to become the first book sanctuary city in the state. The next day after the news broke, a library trustee of another library read about what we did and reached out, asking how they could do the same thing. From there it’s grown library by library, mostly word of mouth, always initiated by the small action by one person.

The Book Sanctuary Movement

EA: “Hoboken Public Library became the first book sanctuary in New Jersey, and now over 33 libraries in the state have followed. What impact has this had on communities and library systems across the state?”

It’s been overwhelmingly positive, and that’s because the book sanctuary statement affirms the values held by members in their community. I call them ‘the silent majority.’ People are so proud when they learn their local public library has taken a public stance in defense of the freedom to read. The book sanctuary resolution itself is very flexible and can be adapted and customized to each community, and I’ve shared examples of how those look like on our FAQ.

EA: “How do you envision the book sanctuary movement growing, and what needs to happen for this model to be adopted on a national scale?”

It’s continuing to grow both here in New Jersey and nationally. We’ve helped states like Georgia and Kentucky with their first book book sanctuaries. We’ve been a resource for many libraries who may be thinking about becoming a book sanctuary. I’ve spoken and presented on this at state and national conferences and I freely give my contact information to anyone who is considering becoming a book sanctuary. The network of libraries around the country is big, but we’re also separated by less than six degrees so word gets around. I really like the organic growth of the movement, which to me is more natural and sustainable.

Legislation to Protect Intellectual Freedom

EA: “Several states now have legislation either in place or pending to protect libraries as book sanctuaries. What is the significance of this legislation, and how might it influence the future of libraries in America?”

Americans love their libraries; moreover they trust their librarians. So I see the spate of pro-library legislation as an assurance that libraries will continue to curate collections that reflect the diversity of our communities, provide free and open access to those collections, and that library staff will be able to safely serve all members of our community. We believe the legislation that we have proposed, the Freedom to Read Act (bill S2421), is a model bill that will do just that.

EA: “Do you think national legislation could emerge that mandates all libraries be free from book banning pressures, and what would that look like in practice?”

We’re already seeing action taken at a national level. Last year the Biden-Harris administration appointed a coordinator in the Department of Education’s Office for Civil Rights to specifically address book bans. And as you stated above, we’re seeing more states introduce legislation that would enshrine the right to read and provide protections for librarians.

Challenges and Pushback

EA: “With book banning becoming a politically charged issue, have you experienced any pushback or resistance, and how do you handle those challenges?”

We’re fortunate to live in a very accepting community here in Hoboken, a “fair and welcoming city” as Mayor Bhalla declared when he was sworn into office. Whatever resistance we have received has largely been from outside our community – and yes sometimes out of state.

EA: “What advice would you give to library directors in states where legislation or community pressures are making it difficult to provide access to certain materials?”

Our sister library in rural Kentucky, Paris-Bourbon County Library, became a book sanctuary after they were swamped with over 100 book challenges from a family who wanted to remove any and all books that were about or by LGBTQIA+. The local community came out in force for months in staunch support of the library, to ensure that these materials were accessible for everyone because they so fiercely believed in the First Amendment. This is the story I tell library directors in more conservative communities, but also because it’s my favorite one to tell.

The Future of Libraries as Intellectual Hubs

EA: “Given the rise in censorship, how do you see the role of libraries evolving as spaces for intellectual freedom and diverse perspectives?”

It’s absolutely essential. The public library in America was created as a space for free and open access to information and knowledge, a leveling field for learners and explorers. It’s democracy in action. Libraries have always adapted our spaces, programs and resources to serve the evolving needs of our communities, but what hasn’t changed and will remain core to our existence is our commitment to intellectual freedom and access to information.

EA: “What do you hope the legacy of this book sanctuary movement will be for future generations of readers and librarians?”

Sometimes the quieter actions make the widest ripples. The book sanctuary is one of those quiet but powerful acts.

Expanding the Book Sanctuary Model

EA: “How might the book sanctuary model be expanded beyond public libraries—perhaps into schools or universities?”

We’ve received inquiries from schools and universities who are interested in adopting the ethos of the book sanctuary. Academic freedom is paramount in academic libraries so the issue of censorship isn’t nearly as active as it is in school and public libraries but nevertheless it’s been heartening to get inquiries. For school libraries, one possibility that may be most effective is a student-led book sanctuary, even if it’s just one bookshelf in the library.

EA: “Have you collaborated with other organizations, authors, or activists who are also advocating for intellectual freedom and fighting against censorship?”

Absolutely. This work is only possible through collaboration and partnership. We work with civic organizations, faith-based organizations, authors, publishers, educators, elected officials, etc. because libraries serve everyone.

Personal Reflections

EA: “What book, in your life, has had a profound impact on you, and why would it have been a loss if it were banned?”

This is almost impossible to answer! So many books have helped to shape the way I think and perceive the world. I didn’t read “The Handmaid’s Tale” until I was an adult, and it’s still one of the most frequently banned and challenged titles. I’ve always loved apocalyptic fiction but this story in particular struck a nerve with me as it felt so much closer to becoming a reality. But any book banned is a loss to the world, because for every book, there is a reader.

EA: “Looking back, what do you hope your legacy will be with the work you’ve done to protect intellectual freedom and promote the idea of book sanctuaries?”

We as librarians are stewards of the buildings and the resources entrusted to us: what will endure is the legacy of the public library, and all that it represents.

Experience the evocative poetry of Natalia Toledo, presented in Zapotec, Spanish, and English. These poems explore themes of boundaries, migration, and sacred places.

Translated by Diego Gómez Pickering, they offer a deep dive into cultural and personal landscapes.

Ra biziaa ca lindaa

Ridide’ ca dxi nexhe’ lu xhaga ne ná’ ca gue’tu xtnine’.

Rarí’, ndaani’ yoodi’, ma gaxti’ xhaga ne ná’.

Bixhozedu biasaca’ ne zineca’, ladxido’do’.

La herida de los linderos

Paso mis días sobre las mejillas y los brazos de los muertos.

Aquí, en esta casa, ya no quedan mejillas ni brazos.

Nuestros padres migraron y con ellos, nuestros corazones.

Boundaries’ wounds

I spent my days between the dead’s cheeks and arms

Here, at home, there are no cheeks nor arms left

Our parents migrated, and our hearts with them.

*

Beelayoo

Xoopa’ gayuaa gueere’ bi

ridxaa ti binni huala’dxi’,

beelayoo naca guie

gundaa laanu ne nisadó’ nayaase’.

Lu ti ndani guie guirá iza risaananu guie’,

ne lade ca guichiyaa, riuunda’ xtinu ma ziyaca nayati.

Ca lindaa nandxó’ guca’ xtinu

nisi ti neza bandaga guie’ naguiichi riaana.

Carne de casa

Seiscientas varas de viento

por un indio,

linderos de piedras

nos separaron del mar mulato.

Acantilado en donde todos los años dejamos flores

y entre huizaches, nuestras voces cada vez más débiles.

De nuestras mojoneras sagradas

solo queda un camino de pétalos espinados.

House game

Six hundred sticks of wind

by an Indian,

stone boundaries that

kept us away from the mulatto sea.

A cliff where every year we leave flowers

and amongst huizaches[1], our voices increasingly weak.

Of our sacred markers,

there is only a path of thorny petals left.

*

Guichigeeze’

Sica lidxi bizu

lade za zeeda ca ridxi yati xti’ ca xiiñu’

bireecabe guiidxicabe sica za bidó’ ladxidó’cabe

gui’di’ ñeecabe ca guiichi nuu guidxilayú.

Ma bixiá xtuba’ ca’ binnigula’sa’

ma bixiá ra bizee necabe ne rinni xticabe.

Ma bisabacabe laya bigose

guxhacabe laa guixhe ni bisabane biní

Ra ga’chi’ ca bidó’ xtiu’

guiiba’bi xti’ dxu’ guxha’ laa.

Espina de pinole

Como enjambre de abejas

de las nubes baja el zumbido de tus hijos,

exiliados abrazan su corazón de cera

con la que pegarán sus pies a las espinas de la tierra.

Ya no existen las huellas de los antiguos

ya borraron donde dibujó su sangre.

Al zanate lo han desdentado

le quitaron la red con que sembraba semillas.

A tus lugares sagrados:

ventiladores extranjeros los han exhumado.

Pinole[2] thorn

Like a swarm of bees

your children’s humming descends from the clouds,

exiled, they embrace their wax heart

with which they will glue their feet to the earth’s thorns.

The ancestors’ footprints no longer exist

where their blood was drawn has been erased.

The rook has been left toothless,

the net used to sow seeds taken away.

Your sacred places:

have been exhumed by foreign fans.

[1] A type of acacia abundant in Mexico.

[2] Roasted corn flour, sometimes sweetened and mixed with cocoa, cinnamon or anise.

Here are eight highly anticipated titles set for release this summer that are guaranteed to keep you captivated and on the edge of your seat.

“I Was a Teenage Slasher” by Stephen Graham Jones

Set in 1989 Texas, this novel tells the story of a teenager cursed to kill for revenge, blending slasher horror with personal reflection. Released July 16, 2024, by Saga Press.

“The God of the Woods” by Liz Moore

This novel intertwines the stories of a wealthy family and their working-class neighbors, all connected by the mysterious disappearance of a young girl at a summer camp. Released July 2, 2024, by Riverhead Books.

“The Haunting of Hecate Cavendish” by Paula Brackston

Set in 1881 England, Hecate Cavendish can see ghosts and starts her new life as an assistant librarian in a cathedral with a magical collection of books. Released July 2, 2024, by St. Martin’s Press.

“What Have You Done?” by Shari Lapena

This domestic suspense novel follows teenagers in a small Vermont town who tell ghost stories, only to find their own lives becoming intertwined with dark and mysterious events. Released July 30, 2024, by Penguin Random House.

“Cuckoo” by Gretchen Felker-Martin

A gripping tale of five queer kids sent to a conversion camp in the Utah desert, where they confront an otherworldly evil. Released June 11, 2024, by Tor Nightfire.

“Youthjuice” by E.K. Sathue

In this chilling novel, a sociopath becomes involved with a wellness company that has a suspicious number of missing interns, revealing dark secrets about its operations. Released June 4, 2024, by Hell’s Hundred.

“The Eyes Are the Best Part” by Monika Kim

This psychological horror follows a college student who must protect her family from her mother’s sinister boyfriend, leading her through a dark journey of rage and revenge. Released June 25, 2024, by Erewhon Books.

“The Handyman Method” by Andrew F. Sullivan & Nick Cutter

A new take on the haunted house genre, this novel explores the horrors of DIY repairs gone wrong, compounded by technological nightmares and graphic violence. Released August 8, 2024, by Gallery/Saga Press.

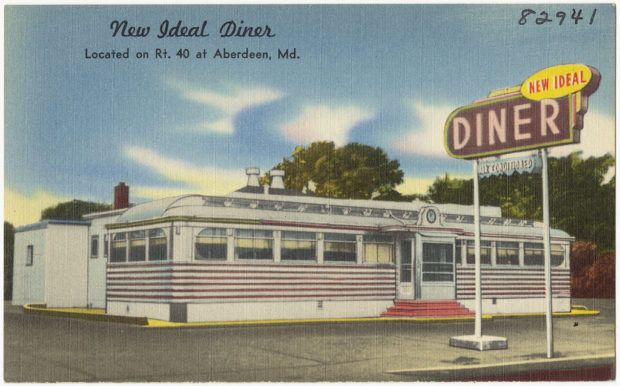

Ode to the Motel

If, as John Cheever once noted, America’s train stations and air terminals are its true cathedrals, motels may be it’s shrines. And if not part of America’s soul, they are certainly part of its circulatory system. Or they were—but I’ll get to that later. The motel was one consequence of the mass-produced automobile, beginning with Henry Ford’s Model T, which gave average citizens the means to chuck—however temporarily—a mundane, shackled life and, as expressed by one of the most resonant phrases in American English, “hit the road.” By the nineteen-teens, many could use their vacations to motor into America’s tradition of nomadic independence, traveling well off the crowded and beaten tracks of mass transportation. Theoretically at least, they could go anywhere in their vast country, at any hour they pleased, for a week or so. Pile the family into the flivver, and it was Goodbye Grundy Center, hello St. Louie. They were pioneers, voyageurs, desperadoes. Escape from the humdrum—the true American Dream.

At first, people needed outdoor gear, for what came to be called “auto camping,” which involved simply pitching a tent by the roadside at night or, later , stopping at a public camp ground. The romantic term for this kind of travel was “gypsying” or “hoboing” (putting aside the fact that real hoboes preferred to take the train). But then, one fine day, at the end of 200 or so sweltering, noise polluted, kidney-tilting miles, behold: backlighted by a Horse Cave, Kentucky, sunset, there it was—Wigwam Village, a set of nine identical cabin-sized cones made of steel, wood, and canvas, arranged to look like a Native American campground, including rest rooms for “squaws” and “braves.” It was one of the earlier motels, built in 1933, when they were often known by such terms as “tourist cabins,” “auto courts,” or “motor hotels.” Scholars disagree on when the first motel appeared, but by 1935 America boasted nearly 10,000, and that was just for starters.

But what distinguished a motel from a hotel, besides the device known as “Magic Fingers,” which, as I recall from my childhood, would make the bed vibrate noisily for about 10 minutes, when it worked? So what if nothing even close to magic or even fingers was involved: it smacked of Scheherazade, and it only cost a quarter. In their heyday, over 250,000 Magic Fingers pulsated bedsprings along America’s highways. But motels involved more than a vibrating bed. Originally, a motel was a place where you could drive right off the highway and up to your room, without having to deal with snooty bellhops and valets. Add to those features the regular sound of trucks blasting by, headlight beams sweeping back and forth behind oilcloth drapes that would never quite close, and, after someone got the bright idea of joining all the cabins into one unit, walls that seemed thin enough to function as giant speaker diaphragms. If your lodging included all or most the above, you knew you were in a motel. The writer Denis Johnson has pinpointed the essence of motel room décor as that which makes the room still seem vacant when you’re inside. But if the décor was often stark and the architecture an afterthought (with some exceptions like those motels built in a style called “Streamline Modern”), most motels had their own identities, thanks to some little touches here and there—if only a weird paint job or a stuffed bird collection. And though many were named after their owners or fancy hotels—the Ritz, the Plaza—there evolved the uniquely motel name. Ever run across a hotel called The No-Tell? The Covert? The Air-O-Tel ? the Bo-Peep? The Lame Duck? Or, my favorite, The Purple Heart, with its dual suggestion of romantic passion and combat wounds? Not a chance. There was also the distinctive bouquet de motel of stale cigarette smoke, carpet mold, toilet sanitizer—and beneath that, a soupcon of diesel fumes and feet.

One other important distinction: The motel was usually near or outside the city limits and was constructed and operated to offer greater freedom and privacy than the busier, more supervised hotel. Consequently, it wasn’t long till the family-oriented ambience of the motel became mixed with something darker. “What better place to take my girl for some heavy petting?” some horny 1920’s college kid must have realized. “What better place to have an affair?” someone else thought. Then those others must have joined the brainstorming, the ones who asked, “What better place to take a break while fleeing an interstate police dragnet?” or to go where no one else has ever gone with rubber, leather, and handcuffs? Or to saw that cumbersome dead body into something suitcase-size?” And so, motels became, at least in the words of a young J. Edgar Hoover, “camps of crime,” or, more popularly and colorfully “hot pillow joints.” Add to the pot the traveling salesman’s discovery of this cheaper, more convenient place to stay and the motel’s distinctive profile is complete.

And wouldn’t you know the arts would stick their noses into the motel’s shadier aspects. Where did Gable and Colbert go in the film It Happened One Night to pull down what they called the “Walls of Jericho”? Where was Norman Bates inspired to make Mom proud and easy to store? Don’t forget that scene in Bonnie and Clyde, where Warren Beatty and Fay Dunaway reenact the real Barrow family’s tourist cabin shootout with the cops. And what do you recall goes on in the famous motel scene in Orson Wells’ Touch of Evil or in the cult classic Motel Hell? But it wasn’t just the movies. Humbert took Lolita to a motel (there were also two movies of that book). As for musical influences, just punch up “motel” on the All Music Guide web site, and you’ll find songs like “Motel Sex,” “Motel Party Baby,” “Motel Street Meltdown.” There’ve been enough similarly-titled poems about motels written in this country to make a genre. And don’t you get the feeling there’s something creepy going on just out side the frame in Edward Hopper’s painting of that woman sitting in a motel room with a Buick Road master staring in the window?

But despite, or perhaps partly because of the real and imagined dark sides, motels remained popular outposts for middle-class America’s escape onto the open road. If the people in the next room looked a little feral, so much heartier the adventure.

In 1954, my family and I experienced what turned into a total-motel vacation. We were going to drive to the Grand Canyon from our home in Omaha. However, being shut up 10 hours a day in a small compartment with his whole family became too much for my father. A mere one hundred miles from our destination, following through on a threat he’d uttered earlier, he turned back, completing the first half of a connect-the-dots, motel to motel foray, from The Big Chief to The Rio Siesta and on and on, including one my father described as being “as close to hell as I ever want to be.” And he’d been in the War. What vacation could be more American?

But for children, motel stops were often the highlight of vacation traveling. Grim as it might have been, the Cactus Motel-Camp could seem like an oasis after spending the day in the back seat rereading comic books and being told, alternately, to stop shoving little sister and stop kicking the back of Daddy’s seat. What former kid can’t recall the amusingly empty threat that “If you keep that up, I’m going to turn this car around right here, and we’ll go home!” Well, empty most of the time. But lets face it : to most kids, a dip in a brackish swimming pool after two bottles of orange Neha from a rusty, top-opening soda machine bested any number of so-called natural wonders. Add to that a snowy, flickering Lucy rerun on a rabbit-eared TV in a room rich in what was termed “refrigerated air,” then top it all off with a bedtime ride on the Magic Fingers magic carpet, and could Munchkins be far behind?

Of course if you’ve stayed in a motel lately, all of this must sound a little unfamiliar. That’s because of two developments, both of which began escalating in the early 1960’s: the interstate highway system and the Holiday Inn corporation. Remember the problem Norman Bates had at the beginning of Psycho? The Bates Motel was usually vacant.

Because almost all the traffic took the “new highway,” no doubt an interstate. Norman and the other independent moteliers were not only bypassed by the interstates but, due to limited-access regulations and, later, Lady Bird Johnson’s campaign against highway clutter, they were often prohibited from putting up signs to tell motorists where to find them. No problem, of course, for the wealthy and influential Holiday Inn and copy-cat mega-franchises, who have tamed the motel into something safe, clean, efficient, and, of course, standardized. Signs aplenty for them. Motels have been made part of what’s called “the hospitality industry,” and most of the ones common folk can afford to stay in are as boring and interchangeable as industrially carpeted cinder blocks, the last places you would associate with “gypsying.” And the line between hotels and motels has gone wobbly at best. You can now find a 10-or-more-story Holiday Inn in the middle of practically any American city. Most of the incorporated motels, which now cater mainly to corporate customers, don’t even use the m-word, preferring that substitute which offers an absolutely false implication of comfy intimacy among traveling strangers. Would Chaucer’s pilgrims have been so relaxed and chatty starting out from the Airport Comfort Inn?

So, though you can still find authentic motels in any of the 50 states, they’re disappearing into pop culture history, along with America’s most motel-friendly highway, our beloved Route 66. But don’t blame Lady Bird or Holiday Inn. We’re the ones who, even in the days of tourist cabins, kept choosing comfort, cleanliness, and reliability over a little roughness, grunge, and adventure. Now, on the interstate, it’s often hard to tell what state you’re in without looking at the small print on the standardized red-and-blue signs. Even the signs that tell you what gas stations restaurants, and motels, are ahead are standardized, as are most of the gas stations, restaurants, and motels. The day may come when you can pull your lozenge-shaped auto up to an interstate McDonalds anywhere in the country and be served by a red-haired, affable kid named, let’s say, Tim, who’ll give you the same polite howdy in Poukeepsie that he did in Minot. When he greets you by name and asks what it’ll be, all you’ll have to say is, “The usual, Tim.” He’ll be electric, of course. Maybe you’ll be, too. So farewell, Purple Heart. Adios, Wigwam Village. We wish we could have been better gypsies.

By John Kucera

A sprawling campsite consisting of beach huts, cabaňas, as far as the eye could see; palm trees; a bright turquoise ocean lapping; it was Playa del Carmen, Mexico, 1996.

I looked it up on Google, it’s nothing like that now. Though I don’t know why I expected that it would be.

I’d not long finished my degree and had my first proper paying job lined up, editing a London magazine; so the idea of a six-month backpacking South American adventure had to be cut down to three weeks in Mexico before starting the new job. While I was away in Mexico, I began to realise that the long-term relationship I’d been in was not going to last forever, though I let it limp on for another four years once I returned to the UK.

My friend from school, R, who now lived around the corner from me in London, had planned the trip with me. We bought a Lonely Planet guide because this was before everyone had access to the internet. Red crosses indicated places that R wanted to go to and a circle around that meant that I wanted to go there too.

I just spent about half an hour on the web looking for the place we stayed on the beach. I couldn’t find it. The five and four-star hotels dominate my search, and I can’t find any rough hewn, palm roofed huts, with space to hang my brand new (never used since) hammock, bought for $15 from a guy wandering the beach.

Tripadvisor reviews say it’s a horrible, crowded place now, that there are more exclusive, quiet places to go. But exclusive and quiet was how it felt, almost twenty-five years ago.

There is no evidence I was ever there.

Everything now is “bonita”, luxury kingsize beds looking out onto the idyllic sunsets, infinity pools and white sand.

One day when we were staying in our hut in Playa del Carmen, we witnessed a wedding on the beach. We were slightly out of season, the weather had become more windy and wet as our three weeks on the traditional backpacking route, visiting pyramids and cities, played out. A bare-footed, dark-haired Mexican couple were getting married on the beach with only a couple of other people. From that moment the romantic vision of getting married on a Mexican beach floated in my mind, though years later, an ill grandmother, meant that I ended up tying the knot in a Bath registry office.

Cabaňas don’t seem to exist now – except at inflated prices, with imitation bare bones facilities – the sand floors, shared showers, do it yourself toilets, and padlock to secure the door, all gone. Replaced with cutesy built on outdoor showers and proper beds for tourists no longer seeking the last dregs of the Hippy Trail. Years ago the open beach bars and beach camping, often run by Europeans who had moved to Mexico’s Riviera Maya, got tarted up, developed, gentrified, so the Ibiza-loving party-goers could dance and drink all night.

I remember sitting in an open bar, rattan blinds blowing in the breeze of the Caribbean, drinking a beer, as backpackers played acoustic guitars late into the night.

The Mexico of my memory from a quarter century ago no longer exists, but I keep the essence of it in my mind, in my heart.

There is a photo of me, standing amidst the clifftop ruin of Tulum; I don’t have the photo but I remember it as if I did, I’m wearing an ex-army jacket that I thought would be lightweight and waterproof, and a long flowing skirt that I’d bought in a beachside store. I wore it on the plane home – and when I was on the tube on the last stage of my day-long journey to Islington from Mexico City, via Paris because the route was £100 cheaper, a woman asked me where I’d got it, because she wanted to buy one.

Twenty-five years is a life ago. Mexico has changed, I have changed, but the image of the happy young bride wearing a short white dress is something burned into my memory.

Mexico wasn’t cool or a common destination when I went, there were no chefs in Mexico City with Michelin stars. There were backpackers and casualties still looking for the Hippy Trail of the 1960s. Maybe there was still something of that easy-going vibe in beachside bars with their two-for-one cocktails with no air-con, and $3 a night rooms in dodgy no-star hotels, where we pretended not to speak Spanish, so we could find out what people really thought of us.

I loved the heat, the wide avenues of Mexico City, though not its pollution. I didn’t have asthma then, and the yellow haze permanently above the sprawling city didn’t concern me much. It was, in a way, almost beautiful.

I was enthralled by the tradition of the flying men of Papantla – the danza de los voladores is a Unesco protected intangible cultural heritage asset. If you’ve never heard of it – look it up on Youtube. Stumbling upon the display in the park next to Mexico City’s Museo Nacional de Antropología, it was a surreal experience, which more than two decades later I came back to in a short story.

Colour and joy; friendly people; absolute contrasts of poverty and riches; green Volkswagen Beetles swarming around the Zócalo main square, cross the road at your peril; chilli; churros; the noise from the jungle from the top of a pyramid; bright wooden carvings of el chupacabra – a mysterious, maybe supernatural monster; white beaches; Colonial cities; brightly coloured patterned cloth; men circling a pole, upside-down as haunting flute music plays… These images are never far from my memories.

Mexico did that. It impressed itself on my mind.

By Sam Hall

The Reeperbahn in the morning is the grass of Waterloo after the battle. Bodies and matter. Broken things. Mostly quiet. No simple task to avoid the glass and vomit and takeaway scraps. Here and there alertness, figures huddled together at benches whose wood is rotten, some with hands wrapped around half-litre beers, others pinching roll-ups. No romance, the bygone charm scoured from the streets.

I am in Hamburg to see the photographer Anders Petersen. There is a retrospective of his Café Lehmitz, analogue captures of one of the red-light district’s most notorious bars back in the 1970s. But that is for the evening. Now is daylight, and I am on the trail of Petersen’s ghosts. The brawlers, beggars, orphans and bastards venerated by Waits and immortalised in Petersen’s celluloid. They kiss, they cry, they dance, they drink. Suited and beautiful, cackling while in states of undress, chewed up and wrung out. Each photo offers a wonderfully tense dichotomy, and is likely the reason why the series remains in print fifty years later.

The actual Café Lehmitz itself is the place to start; I was surprised to find it still listed online. When I arrive, it is closed. A blackened dreadnought with standing tables like concrete crash barriers, the name spelled out in mirror tiles, a disco mosaic suggesting more glamorous times. Tethered to the door handles is a clapboard offering Jäger pitchers. My plan was to sit inside and try to reconcile the black-and-white bar with its present-day counterpart. No luck.

A bearded man wearing a corduroy jacket leans against one of the standing tables. I ask him if the place ever opens. He nods. At four. When I say it looks as like it has been closed for months, he shrugs. It isn’t the real Café Lehmitz, he tells me. That building was torn down in 1987. This one stole its name. I ask him if he used to go there. Sure, he says. All the time. And now? Another shrug. No such places anymore. He asks for some change. I give him five euros and he slips it into a pocket and shuffles away.

I have been duped by the internet and its half-truths. Not the first time.

This isn’t where a twenty-three-year-old kid from Sweden brought his Nikon F and began to shoot back in 1967. This isn’t where he fell in love over and over. This isn’t where he laid the groundwork for a career that would take him from prisons to mental hospitals and around the world. This place is nothing. Disappointed, I cup my hands and press my face up to the glass. No movement, no décor worth mentioning. Still, I came face to face with a ghost. Better than nothing.

I wander away from the squalor, to the harbour, to watch tourists in puffed jackets get battered by the wind coming in from the Norderelbe.

More panhandlers appear on the Reeperbahn as the shadows lengthen, punks in denim and metal with plastic cups that they thrust into the faces of passers-by. At the old Wirtstuben, hard-boiled locals drink Astra beers and smoke Pepe cigarettes. In the chain restaurants, tall Dutch girls order dayglo fishbowls and tacos. There is a McDonald’s that shares the same real estate as a three-storey sex club. The restaurant’s golden arches are sandwiched between windows whose glass is covered in naked blondes. Fresh meat as you like it, two-fifty or thirty-nine euros.

The imposter Café Lehmitz still isn’t open at four. My ghost in the corduroy jacket isn’t there either. A couple doors down, police officers in tactical vests interview a man whose rankness I can smell at ten paces. There is an open sore on his cheek, joining with the nose, and he has no shoes on. The officers wear gloves. A group of stylish French kids waiting at a traffic light make uncomfortable jokes about it.

On a quieter corner I find a bar that claims it has been running since 1911. Inside, smoke hangs like velvet drapes. Locals at four-seat wooden booths. Plants in the windows, boxes resting on stained doilies. Models of wooden ships held together with dust. Bronski Beat, Tina Turner and Talk Talk on the radio. When the barman takes my order, I ask him if they’ve really been open for more than a century. Yes, he says, but not in the same hands. The latest owners, a family, have had it since 1986. Did he ever go to Café Lehmitz? Before his time, he says. He was only a kid. But he knew a man who lived above the bar, his home a lumpy mattress that he shared with another, like Queequeg and Ishmael. What happened to him? Died of an overdose.

I sink into the place and for a few minutes I convince myself this is close. The history, the location, the out-of-time interior. But the characters aren’t right. Locals, yes, but comfortable ones. Hairdressers and HR managers and delivery drivers, not prostitutes or gamblers or drug addicts. These are my parents, lower middle class baby boomers, getting a buzz on before they head home.

When I pay, the barman hands me a belt bag embroidered with an Astra logo. A gift, he says. Sometimes we give them to newcomers. The locals say ciao on my way out.

II

I meet Anders Petersen in the evening. In the gallery there is a good view of cranes and ship cans. Tanned old men and younger women play dress up. Suits without ties, kitten heels, jasmine and ombre leather. The prints are three high on the walls, developed in a Stockholm darkroom in the mid-1970s. Petersen sits in the corner of the whitewashed box, a beer on the sill next to him. Slightly stooped, thinning grey hair, hands interlinked on his lap. When I greet him, he peers at me through round black spectacles and turns his head to hear me better.

He tells me the stories he tells everyone else. About Marlene, about Rose, about Lilly. He is put out by how many photos of Marlene are on the wall; he was in love with her, spent too much time photographing her when he could have been documenting other shadows of Lehmitz. There was another girl, he says, who he truly loved. Vanya. 1962. A Finnish prostitute who used her innocent eyes and body to earn all kinds of money. Five times in a night, sometimes. Then gone, disappeared from the scene forever, leaving his heart in two ragged pieces.

Wasn’t he afraid to put a lens in people’s faces? Oh yes, he says, but only in the beginning. Most liked the attention. And what drew him to the café in the first place? He was looking for his friends, he tells me, ones he made five years previously when he travelled to Hamburg at the age of seventeen. Saved money all summer and spent it on a ferry ticket. Of the group, only two were still around. The rest had faded away.

We talk about other things. Knausgård on the toilet. Bukowski’s need for rehabilitation. Architecture in Stockholm. The self-aware moments he has at events like these, when he tunes in to what he’s saying. But mainly we discuss his photos. The fatalism. The occasional horror. The sense of community above all. He blinks a lot as he speaks and he reaches over and clasps my hand or my leg when he makes a point. His voice goes up and it goes down. He looks tired. There is less of him here than in the interviews I’ve seen. Perhaps because he’s talking about Lehmitz again. His ghosts summoned once more for our viewing pleasure and dissection. Or perhaps time is simply catching up with the seventy-nine year old. Eventually, a woman interjects, asks him to sign a copy of his book, forever in print. He clasps her hand and asks for a pen. I slip away, but not before he assures me we’ll finish our conversation. Much later, when I look for him in his corner, he is gone. A Swedish exit.

I speak to the gallery owner about Anders Petersen. They have been friends for twenty years. How does he appear tonight? Well, says the owner. A little tired of being in the spotlight, but they have sold many photos to the tanned old men in their starched shirts. Not the vintage prints on the walls; those aren’t for sale. The edition of a morose Rose and a laughing Lilly that Tom Waits used for the cover of Rain Dogs is sold out. Ten thousand euros per print. A world away from where it was taken. I bet some of those barflies never earned even ten thousand D-Marks, let alone euros, in their lifetimes. The ones who died young, at least.

It feels incongruous.

On the Reeperbahn at half past midnight and it is a snake eating its own tail. Lights and bodies and taxis and sex. The Pink Palace, relatively unassuming during the day, is the loudest building on the block. It hurts to look at. Police everywhere. Kids spill out of a Burger King and into the road and a driver slams his horn. Kebab men sling döner to hungry stag boys who find seats at trestle tables or else right on the ground. Raised voices, a fight that is quickly broken up. Short stories happening everywhere. I linger, but I get no satisfaction from this street. It is too charmless, too plastic.

My hotel is adjacent to the Pink Palace. In my room, I can hear it all. Wild souls and sirens, a white-hot fire slowly burning itself out. It is a while before I can sleep.

III

The morning after. In the hotel room, sunlight evades red curtains and lays in bars on the carpet. Someone vacuums next to my door. Sirens in the street outside. I have a heavy head. I wonder where Anders Petersen disappeared to the previous night. A stroll along memory lane, perhaps. More likely his bed. He is giving a talk about his work later today. Lilly, Rose, Scar, Sara, Sigrid, Marlene, Mona, Elfie and the rest will be looking down on him. His family, his angels, his cross.

The same scene on the Reeperbahn as the previous day. Fresh casualties in a war that doesn’t want to end. A man lies buried in a sleeping bag that rests on a cardboard mattress. Another is passed out in the doorway of a cinema. I stare at the derelicts and the forgotten who have burrowed deep into the seams of this road. Here are Petersen’s ghosts, hiding in plain sight. The difference is they have nowhere to go. In his photos, the hopeless came together, swathed in shirts and ties, dresses and heels, in search of camaraderie. If you squint, they could be movie stars. Today is pure chaos. The hopeless are strewn across the city, homelessness rising, tent cities under bridges and overpasses. There is no togetherness. No community. No safe space. Yes, Petersen’s characters had their own problems, and to romanticise the era without acknowledging its dark side is disingenuous. But the fact is it has been more than half a century since the book Café Lehmitz was published, and in that time we haven’t created nearly enough safety nets to catch those who need catching. All we’ve done is push them further to the fringes than ever before—and price them out of the addresses where they might have found a sympathetic ear or another chance.

The original Lehmitz had a sign over the bar that said: “In heaven there is no beer, which is why we drink here.” Wherever it is they—the lost, the seekers, the indigent—drink now, it isn’t in a place like Café Lehmitz. The concept no longer exists.

Writing: Grant Price // Photos: Daniel Montenegro

She was there when I was born. She’d come to the maternity clinic along with my father, her son, and together they endured the thrill and anxiety that the process of birth always involves. My grandma was solid as a rock and always by the side of her loved ones at times of need, a loving shoulder to lean on when everything had gone pear-shaped. She had a tough life. She survived the vicious decade of the 1940s in Greece when the country suffered the atrocities of the civil war right after the Nazi occupation, which lasted for three years, ended. She lost her elder brother in the war and the trauma never ceased to haunt her even when she began to exhibit mild signs of dementia.

Her name was Helen. A beautiful name. My father hoped that my brother’s firstborn girl, who saw the light of the world only 2 years before my grandma passed away, would be named after her, a sign of profound respect for the woman who raised him. However, the tiny lady was eventually named Olivia, subverting everyone’s expectations. Helen had 4 children and a husband who saw his role as the provider for the family and nothing more than that. She carried the burden while also working as a seamstress to make ends meet. In my eyes, she was a true heroine for all the hardships she faced throughout her life. I looked up to her since I was a little boy.

Even though nobody could accuse my grandma of being frigid, she wasn’t the type of individual to become embroiled in meaningless chit-chat with others. She loved us all profoundly, but always kept a certain distance. It always vexed me that we couldn’t establish the rapport I desired. Perhaps her aloofness had its roots in her upbringing and lost childhood which was marked by her beloved brother’s untimely death. Her mother was a strict despot who firmly believed that austerity is the quintessence of pedagogy. Thus, she never learned how to embrace human contact.

During her last years, Helen’s health was progressively deteriorating, and she’d come to live with our family in order to receive the necessary care. Dementia was added to her chronic hearing impairment that put a barrier to communicating with us. When I talked to her, I literally had to shout to be heard. I caught her many times trying to read my lips and always failing. I used to perceive her semi-deafness as a symbol and metaphor for her detached manner. Her condition saddened me as I was sure that she had such a rich inner world. Even though we didn’t have the opportunity to share our thoughts, I was convinced that she would it would be delightful to sit down and have a long talk with her.

Since she came home, I made several attempts to approach her. I thought that what would work best in terms of effectiveness in communication would be to ask her direct questions about her life and offer her the chance to share her reminisces of past joys and sorrows with her grandson who was a little boy no more. What was her relationship with her five sisters? How stringent her own mother really had been? But what I wanted most deep down was to learn about her ways of coping with personal disasters. I never saw her lose her cool regardless of the predicaments she had to face.

At the time, I was traversing a rough period of depression mixed with addiction issues and chaos reigned in my life and mind. Helen’s stoic presence felt like a divine gift if it wasn’t for her hearing problem that limited her impact on me. I craved for words, wise words by an elderly woman of immense experience. So, one night, I knocked on the door of her tiny room and sat at the edge of the bed. I was feeling so low for such a long time. My parents were loving and caring but the communication between us was broken, mostly due of my persistent lies and precarious lifestyle. I told her in a loud, but soft voice:

“Grandma, I wanted to ask you something and I want you to be honest with me. Is it possible to return? Can I ever be the person, the good person, I was before? I feel dirty, ugly and old. I’m lost.”

She took a long stare at me and said nothing. This startling confession was the bravest act I made in my entire life. I got up from the bed and I was ready to exit her room, sure that she hadn’t heard a single thing. As I was putting my hands on the door’s handle, I heard her articulating: “Dear boy, a man is more than his worst deed.” Since then, this aphorism became my beaconing light.

I was there when she died. One sizzling, hot night in July, right after dinner she complained of stomach pain and went to lie down early. Half an hour later she was dead. The doctors said that the cause was a massive heart attack. Her loss felt like a stab in the heart. I had never cried as much as I did the days after the event. The funeral was austere and attended by friends and relatives who felt obligated to pay farewell to a good woman. My beloved, deaf Grandma.

By Dimitris Passas

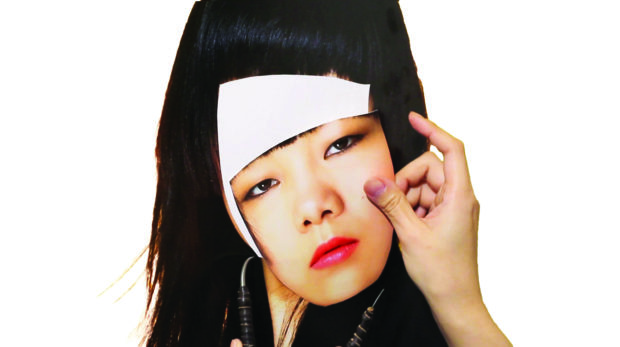

By Xie Hong

Supposedly I should be keen on immigration, for I am from a Hakka family whose tradition is traveling around. In fact, I didn’t plan to immigrate anywhere at first, because along with my growing older, I have gradually lost my curiosity and taste for practical adventures in an unfamiliar environment. Basically, my personality involves impulsion and perseverance and patience, but I am far from an adventurous man.

Of course, I am still curious about the foreign world, which seems contradictory to what I said above, but is very common for the middle-aged. Being curious, I mean, is from my own imagination, which has been developed from my miscellaneous and extensive reading, and from my habit of consuming Hong Kong TV and radio programs for many years. It seems that my consciousness has been reshaped by many cultural shocks and I have been living in foreign worlds for many years.

On the other hand, I am not new to the outside world, at least in the sense of its spirit, which is familiar to me. This spiritual communication in my imagination has become very important in adjusting my attitude towards going abroad and opening up. When I landed at Auckland airport, seeing low houses nearby, I felt a little bit disappointed, but soon I began to cheer up when I found the beautiful scenery around them.

What I saw justified what I had imagined about “the West,” and I even came to realize that the fairy tales I had read must have happened in such an environment, while the art of the oil painting must have been created in this scenery.

Fresh feelings of being clean, comfortable, bright and excited were just like the feelings of the year when my family went back to their hometown, Shenzhen, from inland China. I didn’t know what I was going to do in my future, but I was very sure that I had hopes for it. The most enthusiastic time was the period when I hadn’t settled down, and kept moving around, taking part-time jobs after school. I came here not to my further study; rather, I came here to observe the student life compared to that of my wife and others with similar experiences.

At that time, my wife had great expectations for the future: at the age of 40, she had resigned her job to study in a new country. Such an approach was common among mainlanders who fled to Shenzhen to make a new and different life. In the beginning, my wife regarded her study abroad as a rest or a break, and planned to go back home in a year or two and settled down again in Shenzhen. But she decided to stay in New Zealand before she had completed her second semester.

My attitude was unclear because I was more hesitant to start the second phase of a different life. It meant we had to start from scratch in New Zealand! Accordingly, I really didn’t like to make that decision, and kept it vague and ambiguous. “If you want, you could withdraw to Shenzhen whenever you like,” I told her. This was my attitude; besides, I could not give her more help.

Before her leaving for New Zealand, our life in Shenzhen was satisfactory and comfortable; I had made a long-term plan for my writing career, and had already achieved some great progress, so I always declined any long trips. After I resigned from the bank, I had planned to go to Beijing for a better chance; however, after my first-hand investigation, I found that it was not suitable for me to restart a new life in a new place because I could not adjust myself to certain circles of friends. After that investigation, I stayed safe in Shenzhen to continue the development of my writing.

Again I was now facing the same choice to make. This time I felt I was going to be uprooted; what was worse, this time we would go to an unfamiliar place millions of miles away. Although New Zealand was beautiful and tempting, being a realistic idealist, I was still not in a position to make a decision after my investigation. With my wife’s encouragement, I kept on travelling between Shenzhen and New Zealand. She always comforted me by saying, “A lot of people in New Zealand are indies like you.”

This was not very rhetorical, but it hit it off with me. The reason that I didn’t want to come to New Zealand was that I didn’t want to start from scratch again, and my life goal is not working to make a living, but to be able to achieve something big in literary creation which enables me to mount the top of the pointed pyramid of literature. The reason that I quit a good job at the bank was also for the above-mentioned goal.

After my wife graduated and found a job, I arranged my family’s immigration, and finally settled down in New Zealand, gradually finding many problems in our daily life which had been overlooked before. For example, after gaining our identity cards, my wife considered resigning and starting a business. Do you want to change your job? To do what? All of this had been considered as a holistic plan: my wife would have thought her working experiences in gardening and greenhouses would help her rent some tents for planting lettuce. We also ran around looking for the ideal vegetable field, and wanted to work in fast food restaurants so we could later open a shop of our own. And so on and so forth.

Finally, all plans failed us because after 2008, the global economy entered recession, and New Zealand was no exception. In the evening newspaper, the recruitment advertisements were dwindling, so we had to seek a different approach: my wife was reminded of her past in part-time cleaning job, and heard that early Chinese in New Zealand had earned their first bucket of gold in it, which had inspired our entrepreneurial passion; then we chose cleaning as our business.

In the beginning, it was hard for us, but it brought quite a nice income which enabled us to make an ambitious plan, namely, to pay our home loan debt within five years. Yet it was not as simple as we imagined. Although we worked hard and our service was of good quality, we found that as franchisees it was difficult to control our own business contracts, because we lost some of our customers for some weird reasons; later, we found out that it was a common trick for cleaning franchisees to not be able to control their own businesses! We kept our bitterness in our hearts and comforted each other by asking why we were so tired. Relax!

Such a situation would easily make someone give up on himself. I often reflected in my mind whether it was worthwhile to live such a life here and give up our comfortable home in Shenzhen. My wife worked very hard, and she even did the work for two people; for me, I was also constantly busy trying to find a better job opportunity, but before you are successful, when your pace of life is slowing down or stopping somewhere, you will surely have confusion in your heart.

Based on these experiences, when I was consulted by friends about immigration, I advised them to think carefully about it because it would involve more of their family affairs than expected, and they would have to be cautious. Still, this topic of immigrantion remains so tempting to them.

Some people think that since they have done well at home, why go abroad? But others argued with me, saying, “You say it is bad to emigrate, so why do you want to do it?” These questions make me really speechless. All I can say is, “Firstly, you need to travel for real experiences, and let other things speak for themselves slowly.” I added, “The environment is good, but the reality is cruel.”

That sounds scary to some people, yet no one is willing to accept it. The latter part of the sentence is the most easily overlooked. At the beginning, when someone said he would go to Shenzhen, did your friends express the same opinion to you? When they did settle down in Shenzhen, they all brought their expectations into truth. It was the same thing here. You have emigrated to New Zealand, but you tell them that New Zealand is not good, so how could you expect them to believe you?

One of my friends was such a good example: when she planned her emigration, I gave her a stern warning like that above; however, it was useless to her. After she had studied in New Zealand, she realized that it was a wrong decision, and then she had to go back to China, having wasted much money and time. Drawing a person out of their comfortable nest is a difficult thing, especially for the middle-aged who feel so good in their domestic life and should act prudently.

Before making such a decision, you must understand the purpose of your emigration. Do you wish to give your children a good start in life? Or to give yourself a new starting point? Or if you have been wronged at work or have suffered a failure in your business, do you bet you can restart them in a new place?

Based on my experience, the middle-aged should avoid such a crazy challenge. In New Zealand, if you want to find a good job, you have to earn a local degree, and you should spend more time and passion in job hunting. Most people still feel it very difficult. When I recalled my early days after moving from the mainland to Shenzhen, I was proud to say that I had tasted what was bitter in life. Like others who were in Shenzhen for a better life, I really did not fear any hardship; now, however, I have been changed and become really afraid of any suffering. Nonetheless, I choose to stay in New Zealand because I believe that my wife can bear any challenge we face.

Reviewing my earlier days in Shenzhen, those who went there held to their dreams, and for these they were willing to endure any hardship. Likewise, we have similar expectations in New Zealand. If you are as common as stars, if you have no important relatives or high social position, if you just depend on your own industry for a stable life, then you can emigrate to New Zealand as the best choice.

On the other hand, if you have a certain successful business in China and you want to start a New Zealand business, you should be very careful with your decision. If you have already made enough money, you are welcome in New Zealand, which will be a heaven to you; otherwise, without enough money, and doing a job you dislike, you can comfort yourself by saying, “Here we have safe food and other safe stuff; people here follow the rules, and everyone plays fair.” But at the bottom of your heart, there is always a deep sigh: your life here is still inferior to the comfortable old homeland one.

To be a migrant or not? There is no standard answer, indeed. It depends on your own case, or your attitude. Concerning our family moving from northern Guangdong to Shenzhen, it was not good for my father, but it was lucky for us kids. At last, of course, my dad’s retired life is lucky, too.

By William Blick

Many great artistic movements have sprouted from the seeds of economic depression, and Argentina has had its share of economic hardships. Therefore, it can be surmised that from these difficulties, a new film movement sprouted from Argentina. At the core of the movement currently, is a production company known as “El Pampero Cine.” History has demonstrated that adversity has been the ally to innovation and this idea is central to El Pampero Cine.

Tamara Falicov, writing for MUBI notebook, traces New Argentine cinema to an upsurge all the way back to the 1990s which was related in part with a small grants program that was initiated by the National Film Institute (INCAA).[i] Film institute graduates, like those of new American indie cinema of the early 1970s such as Scorsese, Spielberg, and De Palma, made short films or (cortometrajes), and then went on to raise funds through co-production funding. “They have relied on their own networks of like-minded young people rather than depend on the traditional film sector structure (the film union, established director’s associations, and the few film studios still in existence).”[ii] It is not uncommon for like-minded artists to bind together to support a new aesthetic. This has occurred not only in film, but in literature, poetry, and visual arts.

Hamed Sarrafi writing for Senses of Cinema discussing Laura Citarella, a founding member of El Pampero Cine, and her latest film: “following in the footsteps of most El Pampero Cine movies, Trenque Lauquen reveals itself as an epic that eschews flashy aesthetics in favor of subtle, introspective storytelling, captivating viewers completely. Rather than appealing superficially to the senses, it chooses to delve deep into the human psyche and soul.” [iii]Flashy aesthetics indeed are not part of El Pampero Cine, but there appears to be an element that can be construed as gimmickry. I might feel this way if I were cynical. However, by viewing these films there is a sense of invigoration and excitement about cinema that hasn’t been felt, at least for this writer, in years. Not since the 1970s, arguably the best years for cinema ever, has there been this renewal of enigmatic storytelling.

New Argentine cinema according to Falicov is different from the previous auteurs of Argentine cinema as former directors had created gritty, realist dramas reminiscent of the political cinema of the New Latin American Cinema movement of the 1960s and 1970s. The New Cinema’s films created are not overly concerned with politics. Falicov says, “they are working to expand the notion of Argentine citizenship to include subjects and characters who have traditionally been invisible or excluded from Argentine screens.”[iv]

However, despite El Pampero Cine being an eminent, driving force in cinema, few Argentine citizens (or many, many people) actually watch these films, as Falicov notes. Filmmakers obviously want their films to be seen even if they do reject traditional aesthetics. According, to Falicov: Box office figures for these critically acclaimed films range on average from $100,000-$250,000, and producers claim that a medium budget film (to a tune of $1.5 million) film must make $500,000 to turn a profit, since ticket prices are so low.”[v] Like independent filmmakers all over the world, it takes effort and marketing promotion to get these films seen. However, as a result of low funding, the emphasis is on the art and not the marketing itself. Necessity is obviously the mother of invention in this case, as these filmmakers toil for their art on a shoestring.

El Pampero Cine literally translates to mean “cinema” of the Argentine region known as “Pampas.” It really is a group of indie filmmakers who created an artistic bond, and a purist, experimental form of cinema using minimal budgets, limited casting, an esprit de corps work ethic, and who star in and criticize each other’s films. Also, there are elements of magical realism similar to the writings of Borges or Bolano, and a combination of other aesthetics including genre-bending and experiments with diegetic sound and music. The central directors include within their ranks: Mariano Llinás, Laura Citarella, Agustín Mendilaharzu, and Alejo Moguilansky. The actual production company El Pampero was founded in 2002. The cinema movement still has not reached its peak and is not as well-known as it should be. However, this new wave has the potential to inspire countless generations to come just as the briefer French nouvelle vague and Italian neo-realism has done. El Pampero Cine is unprecedented in their bold, provocative films that break the fourth wall, and with that everything else that can be construed as traditional narrative filmmaking.

A prominent Pampero, Mariano Llinás, created La Flor, a staggering 13 hour film with a series of sinuous plots played by the same four women. I do not know if this is innovation or sheer indulgence, but it is a cinematic achievement any way you choose to look at it and it is like nothing I have ever seen before. An El Pampero Cine film is not like streaming an episodic series on Netflix, although La Flor is available for streaming in episodes and probably the only way you will be able to watch it is like I did, in small increments. I offer that it is an immersive and grueling experience. Sometimes that experience can prove to be painfully slow. Antonioni always made immersive, subtle, and challenging films that were quite introspective, and Tarkovsky’s sci-fi epics such as Stalker are difficult, but none of them are likely to challenge the viewers’ attention span like El Pampero Film. Take La Flor, wherein some of the plot lines are resolved and others are not, and there is not always a sense of closure. New Argentine filmmaking is unapologetically demanding. Beginning scenes lasting a large screen time evolve with no dialogue or in the case La Flor, the filmmaker lays out the blueprint of the film before the narratives start. The plots are bizarre, experimental, and provocative. A film like La Flor, covers so many genres including thrillers, spy flicks, and musicals. Many feel that this is what film should be, which is essentially a celebration of film itself.

The sheer ambition of La Flor including the genre mixing, the metanarratives, and the eschewing the traditional narrative as well as the bloated run time reminded me of David Lynch’s Inland Empire (2006). However, El Pampero Cine opts to avoid out -and -out surrealism in the favor of less self-conscious narrative tasks.

Laura Citarella tells Samuel Brodsky in Filmmaker Magazine:

“On the one hand, it starts with the core belief that there is no ‘standard’ way of making a film. Films are not static and repeatable structures, and our job is to believe a lot in the possibility that each film reinvents not only its fictional universe and its internal logics, but also its own way of being produced, of being thought of, and ultimately getting made.”[vi]

If cinema is truth 24-frames-per second according to Godard, then Citarella and her cohorts have invented a new way to illuminate truth through stylized and innovative approaches to narrative such as Trenque Lauquen Part I, which is, at its core, a thriller, but by no means conventional. Again, run times of Pampero films appear ostentatious, but if the narratives earn it, then so be it! Pampero films may infuriate and fascinate simultaneously. However, it is a worthwhile journey for any film aficionado.

Citarella also said in Filmmaker Magazine that, “Nobody makes a film at Pampero without the rest seeing it and without the rest being able to give their opinion, so it is set up as a form of work, of constant exchange.”[vii] This is such an intriguing aesthetic concept. It is obviously not new. However, essentially what the filmmakers are doing is workshopping their films and continuously learning as if they were still in film school. They are actively producing films that are continuously being created and reworked.

El Pampero Cine’s Dossier proclaims:

More than just a simple production company, it is a group of people keen to bring experimentation and innovation to the procedures and practices involved in making cinema in Argentina. As part of the formidable rebirth known as Nuevo Cine Argentino, bringing with it films like Mundo Grúa by Pablo Trapero, La libertad and Los muertos by Lisandro Alonso, and Los guantes mágicos by Martín Rejtman, the output of El Pampero Cine has seen some of the most original and celebrated films of the last ten years. Films which have taken innovation to practically all areas of film activity.

If you have not heard of El Pampero Cine films, you are probably not alone. Although they have won hearts and minds all over the world and won numerous awards at Film Festivals they still are a fringe film surge, and the material and subjects are still marginalized. Many of these films can be found on streaming services and I am grateful for this. I had first encountered El Pampero Cine after reading the interview quoted in this article with Laura Citarella in Senses of Cinema.

New Argentine Cinema lends itself to comparison with numerous other movements for example Dogme ‘95, New American Cinema, and of course New Latin American cinema. El Pampero Cine is revolutionizing cinema as we know it and this revolution is not being shown enough. Slowly, but surely New Argentine films will take their place where they belong as some of the freshest and most innovative in the world.

Films

• Un Andantino (Alejo Moguillansky, 2023)

• Clorindo Testa (Mariano Llinás, 2022)

• Trenque Lauquen (Laura Citarella, 2022)

• Clementina (Constanza Feldman / Agustín Mendilaharzu, 2022)

• La Edad Media / The Middle Ages (Luciana Acuña / Alejo Moguillansky, 2022)

• Corsini interpreta a Blomberg y Maciel (Mariano Llinás, 2021)

• Concierto para la Batalla de El Tala / Concert for the Battle of El Tala (Mariano Llinás, 2021)

• La Noche Submarina / The Submarine Night (Diego H. Flores, Alejo Moguillansky, Fermín Villanueva, 2020)

• Un día de caza / A Hunting Day (Alejo Moguillansky, 2020)

• Lejano interior / Far Interior (Mariano Llinás, 2020)