You have no items in your cart. Want to get some nice things?

Go shopping8 minute read.

When a roots, rock, reggae artist shouts,“Jah,” my spontaneous response is “Rastafari”—a ritual I acquired after many years of attending reggae festivals, especially the Bob Marley Festival at the Long Beach Convention Center. Those annual Marley celebrations, now defunct, were held over the three days of President’s Weekend to commemorate the February birthday of the late reggae icon, and they included not just roots rock, but lovers rock, and dancehall as well.

I became such a festival diehard that one year I went beyond being a simple fan—I decided to sell Rasta-inspired Guatemalan handcrafts in the market area of the concert. Mind you, these were handcrafts that I personally brought back from Guatemala’s Central Market. Not surprisingly, celebrating the Marley Festival as a concertgoer was distinct from laboring as a merchant. As a concertgoer, some years I had tickets that restricted me to arena seats, and other years I had general admission tickets that granted me the freedom, during dancehall, to mingle among the crowd on the convention center floor and wait for the rude boys to run the riddim. As a merchant in the selling hall, the music was a distant beat, and my body was confined to the cavernous hall and small table where I was selling my wares. Years before the Long Beach concerts, my Chicago-born mother had introduced me to Marley’s music when she took me to see the world-renowned artist live at the Greek Theater in Hollywood.

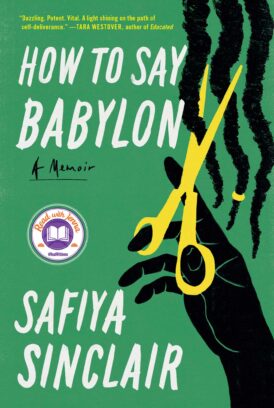

No surprise then that when I came across Safiya Sinclair’s memoir, How to Say Babylon, I was down for the read. Yet I was not prepared for this tale about the confinement and strict limitations placed on the female body.

The Clash of Beliefs

In the U.S. our notions about the female body are a legacy of Western colonial traditions. The same binary logic inherent in Western thought that justified the imperialist domination of the globe and the marginalization of non-European bodies also viewed men as strong and rational and women as weak and emotional. In the imperial binary oppositions (that still permeate society today), Europeans were civilized, the Indigenous were savages. White people controlled the destiny of Black people, and Christianity was regarded as superior to Indigenous spiritual practices. Industry was king and nature was to be commandeered. These principles regarding inherent difference and superiority coupled with the genocide of Native Americans and the enslavement of Black people formed the basis of the industrial revolution on which Europeans reinforced their beliefs of supremacy.

Jamaica, the birthplace of Safiya Sinclair, was likewise subjected to the oppositional binaries of its British colonizers. In her memoir, How to Say Babylon, Safiya Sinclair discloses her entrapment within the binaries fashioned by her father’s interpretation of Rastafari. She relates how the Rastafari religion was developed in the 1930’s by Leonard Howell who was inspired by both Marcus Garvey and Karl Marx. Howell’s commune and its teachings served as one of the foundations on which Rastas expounded their belief that Ethiopian Emperor, Haile Selassie, was the Messiah. Honoring the fundamental guidelines of peace and harmony, Rastas interpret their basic tenets distinctly.

Sinclair describes how her father’s religious practice wasn’t performed inside a church. Instead, he attended meetings, and women were not invited. Of the three Rastafari groups—the Twelve Tribes of Israel (the most liberal grouping which also allows White members), the Bobo Shanti, and the Nyabinghi (the strictest grouping), Sinclair’s dad was most aligned to Nyabinghi beliefs. Yet he was never a member of any specific organization. The irony in the Sinclair household was that despite her father’s efforts to avoid the conventions of colonialism, he raised his children in a home in which his view of the world was based on an oppositional binary. His outlook on women, which resulted in his making almost all the decisions in the household, caused the writer the most distress. Sinclair, her sisters, and her mom were assigned domestic duties while her dad savored the freedoms found in greater society. In addition to assigning housework, her father demanded his daughters remain chaste. In her dad’s household, Safiya Sinclair could either be associated with Rastafari or lost to Babylon. There was no in between.

Despite the book’s title, the memoir doesn’t deliver a lucent depiction of Babylon. It is the dad’s interpretation of Rastafari that dominates the narrative because as females, Sinclair and her sisters are forced to exist within the religious strictures of their home when they are not in school. As a consequence, Rastafari becomes the string of households the three sisters and their brother inhabit as their parents move from home to home surviving on the dad’s earnings as a reggae musician. The dreadlocks everyone in the family dons and which the author wore for ten years are a symbol of their religious convictions. Based on her father’s interpretation, Babylon is everything outside his home and everything in opposition to Rastafari. Babylon is Western ideology, colonialism, and the brand of Christianity that led to enslavement. It is baldheads and heathens—the unprincipled men and women who populate degenerate society. And it is the Jamaican military and cops who on Bad Friday in 1963 cut the dreads of Rastas, destroyed their encampments, and proceeded to jail and torture them. Yet when the author arrives to the U.S., she realizes that the slavery, genocide, and violence of this country are Babylon too. At that point in the book, I wanted to ask Sinclair to hold her thought and dig deeper into her analysis. I would have liked for her to explore these analogies further.

Personal and Inherited Trauma

Sinclair uses a mostly linear narrative to express the anguish of her own upbringing and that of her dad. Born to a fourteen-year-old mom, he suffered feelings of abandonment as a young adult when his mom left to live with a new husband and told him he wasn’t welcome. His feelings of rejection were a catalyst for him to delve deeper into religion and eventually choose his version of Rastafari as the unnegotiable belief system in his own household. It isn’t until almost the end of her memoir that the writer begins using the words abuse, trauma, and inherited trauma. She confesses that she began writing this book in 2013 and was advised to hold off writing it in order to distance herself from her traumatic experiences. Thus, she perhaps didn’t use the word trauma in the beginning of the narrative because she hadn’t initially viewed her experience as such.

During the author’s early years, her mom acquiesced to the father’s domination of the household that eventually developed into physical beatings. Sinclair’s flight from her father’s abuse occurs as her education advances and she is able to visualize an existence beyond the false binary of Babylon vs. Rastafari.

Comparative Insights

As I was reading Sinclair’s book, I came across a short essay in Brevity by Zach Semel titled “Why I Wasn’t Ready to Go to AWP This Year.” Examining the topic of memoir writing and trauma, Zemel recalls attending the 2023 Association of Writers & Writing Programs conference and describes the challenges he is currently facing in writing a memoir about his “experiences living with PTSD in the wake of the 2013 Boston Marathon Bombing.” His reference to the anthology by Melanie Brooks titled Writing Hard Stories: Celebrated Memoirists Who Shaped Art from Trauma led to my purchasing her book in the hope that it would help me better understand Sinclair’s How to Say Babylon.

Brooks’ Introduction and her interviews with Edwidge Danticat, Kyoko Mori, and Jerald Walker left me with a better understanding of what these writers were attempting in their act of writing memoir. Danticat’s memoir focuses on the deaths of her father and his brother, both of which occurred within five months. Her dad died of cystic pulmonary fibrosis and her 81-year-old uncle died of acute pancreatitis in US immigration detention after fleeing political unrest in Haiti. Mori writes about her mother committing suicide when Mori was just twelve and the emotional and physical abuse she later suffered at the hands of her dad and stepmom. And Jerald Walker’s second memoir expounds on the decision of his blind African American parents to join a white supremacist doomsday cult and how that affected his development growing up a Black child. In Writing Hard Stories, these writers delineate how writing about trauma created a sense of cohesiveness, accomplishment, freedom, and healing. They speak about finding their voice while writing and leaving an authentic legacy for their families. Their explanations about content and writing process illuminated the agonizing details of How to Say Babylon.

Additionally, once I finished reading Sinclair’s memoir a virtual lecture surprisingly popped up titled “Women and Rastafari Politics, 1934-1960.” I eagerly attended with the goal of gaining a wider perspective on the role of women in the Rastafari movement. This was a University College London event in which professor Daive Dunkley, Chair of Black Studies at the University of Missouri, discussed his book Women and Resistance in the Early Rastafari Movement. (In accord with the admonitions to fight “against ism and skism” in Bob Marley’s song “One Drop,” Dr. Dunkley refers to Rastafari and not a closed system of Rastafarianism.)

In his talk, the scholar demonstrated how women in the Rastafari movement had leadership roles from its inception in the 1930’s. He gave the example of the Rastafari woman Delrosa Francis who was charged in 1934 with assaulting a police officer. During her trial, Rastafari women came to her defense and expressed the Black nationalist view of wanting the British colonizers out of Jamaica and demanding the island be turned over to the Ethiopian government. In much greater detail, Dunkley gave the example of Edna Fisher who established the African Reform Church in Christ (ARC) in 1959 in Kingston which replaced Leonard Howell’s Pinnacle organization as the most popular Rastafari organization of that time. The ARC, which was birthed in a prayer circle of Rastafari women, grew to 4000 members by 1966. Dunkley described how Fisher worked in conjunction with Claudius Henry whom she later married. The Jamaican government eventually charged Fisher and Henry with treason and sent both off to prison. Following their release, Edna Fisher was assassinated. Professor Dunkley believes that the patriarchal and systematic silencing of women in academic circles resulted in Claudius Henry being portrayed as the leader of the Rastafari organization the two ran together.

Tragic Legacies and Resilience

After reading Safiya Sinclair’s memoir How to Say Babylon, it became apparent that her dad tragically succumbed to the imperial binary systems he had hoped to resist. Tragic because, despite his esteem for Bob Marley and his friends’ high regard for Marcus Garvey and Malcolm X, her father’s worldview was based on a male/female binary that obscured and excluded the entirety of the legacy of freedom fighting by women. Fortunately, the research of Daive Dunkley highlights the historical contributions of women to both the Rastafari movement and Jamaican society. And fortunately, writer Safiya Sinclair was determined to have a voice in a world that was not built solely by men.

352 pages.

AUDREY SHIPP

Audrey Shipp's writing has appeared in various journals, including Brittle Paper, Isele Magazine, Another Chicago Magazine, LitroUSA, A Long House, and A Gathering Together. She has both a B.A. in English and M.Ed from UCLA, an M.A. in English from Cal State LA, and a Certificate in Creative Writing from UCLA Extension. She is working on her memoir about writing and (un)writing in Los Angeles.

- Web |

- More Posts(1)