You have no items in your cart. Want to get some nice things?

Go shopping

With Once Upon A Prime, I can only take the approach of a non-mathematical layman and give you a taster of what’s to come. I investigate numbers in everyday calculations, transactions, accounts, receipts and in counting coins, before going round in circles, going off at a tangent. Professor Hart, however, has delivered a debut novel that’s got me curious about the relationships between mathematics and literature that goes beyond poetry. She puts two and two together, raises what’s hidden and offers something entirely unique, which needn’t be a conundrum.

Words and numbers are everywhere, if we care to notice them. Take “good, better, best”; this is the beauty of trichotomy, a set of three, based on the Archimedes principle of having two extremes and a middle. It’s like having three layers and an emerging pattern. Looking at the story of Goldilocks, Daddy Bear’s porridge is too hot, and his bed is too hard. Mummy Bear’s porridge is too cold, and her bed is too soft. But Baby Bear’s porridge and bed are “just right.” We have reached a balance (a happy medium).

Aristotle also says that “every ethical virtue is a golden mean” i.e. just right, “between two vices – one an excess, the other deficiency.” Through this I confidently arrive at the essence of compromise – another middle.

It is no coincidence that this book’s title is Once Upon A Prime. Taking the power of three, a prime number, it can only be multiplied by itself and one, and cannot be divided by other factors. Dr Hart refers to this as “threeness.” Three will always have a beginning, an end, and a middle. Just like a story. Three-character patterns appear in nursery rhymes such as The Three Little Pigs, there are three Billy Goats Gruff, three good fairies, three bears, and three brothers or sisters in countless tales. The upshot, Hart explains, is that two repetitions are required to get to know the pattern and once the third iteration arrives, the pattern is broken and surprises, amuses or shocks us. In fairy tale structure the same situation happens twice with the same result. Then with the third character something different happens – and this effects change. We could relate this to Einstein’s madness, often quoted in a business context, of “doing the same thing over and over and expecting different results.”

If we take another prime number, the number “one,” it appears to be the very simplest of them all. Yet in literature – in Beauty and the Beast for example – there is only one beauty, one beast, one castle (i.e. a single location), one enchantress, one rose and one talking teapot. For Hart this number therefore stands apart from other numbers. It is unique and forms the building block of all others that follow. I note there are many permutations and combinations of where it can go, leading even to infinity, with infinite possibilities.

Let’s introduce Pi. Numerically it is 3.14 for those who care to remember. For Hart, the true mystery is how it “manifests itself in the most unexpected places” in mathematics. Many mathematicians (alongside Archimedes) such as Newton and Charles Dodgson (Lewis Carroll to you and me), have tried calculating approximations to but because its digits go on forever (3.14159265359 and so on) we frustratingly can never know its exactitude. Whereas the circle is the most common appearance of the symbol, Sarah explains that

even occurs in the most “meandering of rivers.” If you “divide the length of the river, including all its wiggles, by the ‘as the crow flies’ measurement from source to mouth, the answer approximates to pi.” I am curious about these “approximates” because if everything is an approximation, then one moves further and further away from the exact and heads towards inaccuracy. Surely the river cannot ever be measured exactly?

The best writing too is usually circular in form. The end comes back round to the beginning just as the never-ending digits of lead us to infinity. The most perfect literary example of this is The Library of Babel by Argentinian writer Jorge Luis Borges. Sarah Hart highlights, “paradox, and the infinite – and the paradoxes of the infinite – are a recurring theme here, like a mathematical oxymoron. It shows a finite number of things that somehow have to fill a space that extends forever in all directions.” For me it’s like infinity within infinity that sits inside infinity like a Russian doll, whilst for the author, the real fascination with

is “its mysterious infinitude.”

Borges’s library (aka the Universe) has hexagonal rooms. There are 410-page books of a certain format and character set. The inhabitants believe that the books contain every possible ordering of 25 characters comprising of 22 letters, the full stop, the comma and the space. It already sounds like a mathematical conundrum based on permutations and combinations. It has of course been translated from the Spanish so how can something mathematical not be lost in translation? Many of Borges’ known themes are in the story – infinity, reality, labyrinths, but also randomness. Letters appear at random and the books in the Library are written in an unknown alphabet. Could this be a code, or a pattern in itself?

I see dystopia. Borges however, explains that “the Library is a sphere whose exact centre is any one of its hexagons and whose circumference is inaccessible.” It is genius. The Library has an “indefinite number of hexagonal galleries, “ “from any of the hexagons one can see interminably the upper and lower floors,” “the distribution of the galleries is invariable.” As symbolism and imagery enter into play, Borge’s vision becomes easy to see and Hart’s inclusion of it in her book makes sense.

In the course of Once Upon A Prime, we are informed of the fractal structure of Jurassic Park, algebraic principles, mathematical metaphors in Moby Dick, calculus in Tolstoy, geometry in James Joyce and even mathematical surprises in War and Peace. The beauty of learning is if you don’t know something, you look it up – and Hart has clearly encouraged us to do this with her book. I am curious therefore to know more about its author. She is the 33rdperson and first ever woman to hold the prestigious Gresham Professorship of Geometry, which is the oldest chair in the UK and for her children, it is the most natural thing in the world for a woman to be thinking, talking and explaining maths. For Hart, Maths comes very naturally as her own mother was a mathematician. The book’s idea was born as a lockdown project, developed in the garden shed as a means of escaping the stresses of the time. – how joyful it must have been to be in a world thinking about Maths.

With patterns, as Hart explains, it’s as much about discovering, understanding, spotting and making them, as it is about breaking things up and as a voracious reader from a very young age, Hart was always attuned to the patterns and mathematical metaphors that are everywhere. This adds an extra layer of enjoyment to her work – not all authors of course are mathematical in their writing. I can imagine her mind scanning every sentence. Can sense that she does not rest happy until she finds that mathematical something, whilst admitting that she is never necessarily trying to prove that there is.

Hart confirms that authors do play around with maths, and decribes how she loves to seek out mathematical mistakes. In the case of the Da Vinci code, she admits that with the cryptography, it is not too challenging to break the Holy Grail. On the other end of the scale, there is an old book by Alan Garner called Red Shift in which she still hasn’t managed to crack the code, with the last pages written in encrypted text. She is not too disappointed, though, if nothing mathematical jumps out, such as perhaps is the case with Donna Tartt’s The Goldfinch. There are usually patterns to be found in numbers if you so wish – the human brain likes making such connections. There is a theory that being too logical can make you soul-less, but I suggest that Maths is Sarah Hart’s superpower.

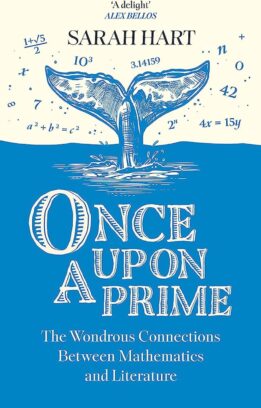

The cover illustration can be seen as a play on words – it’s a tale of a whale which doesn’t necessarily need to be from Moby Dick but can also be the tail of a whale. It makes a splash and indeed this book’s success might well prompt a follow-up – either something in the same vein or something that explores the links between maths and music, art or architecture. After all there is many a mathematical connection in design, engineering, building bridges (metaphorically, literally and physically).

Listening to Mike Garner, author of Stories That Matter, he says that in the most effective writing, we join the conversation that people already have in their heads. Between Harts’s lines there is plenty of wonder and mystery and often a head nodding in agreement or appreciation. As readers we are happy to join this literary mathematical ride, as if to answer what we didn’t know we needed to know and curious to discover something new. This book acknowledges that we need numbers to calculate and words to communicate, translating maths into literary terms and translating literature into mathematical values. I’d say there is a poet in residence beneath every mathematical conundrum that are intrinsically linked. Fact. Or fiction?

Once Upon a Prime: The Wondrous Connections Between Mathematics and Literature

By Sarah Harrt

Harper Collins, 304 pages

Barbara Wheatley

Barbara has a longstanding passion for language and the written word. A reader who writes, and a writer who reads, she freelanced her way in London for 8 years in PR, writing promotional campaigns, press releases, copy, slogans, etc., within the music and entertainment industry. She last promoted PR packages within the Press Association before full-time motherhood allowed Barbara to pursue her interest in Creative Writing. This creative enthusiasm led to 3 unfinished fiction novels. Now a mum to 3 teens, she has been a student on college and university courses as well as workshops and festivals, independently and online. A move to Devon saw her first flash fiction submission longlisted then shortlisted. Her work has regularly been published on Friday Flash Fiction (which also appears on Twitter) and has appeared on Paragraph Planet and several collections of new writing. In the pursuit of her true writing voice, she concentrates nowadays on Creative Non Fiction, where her experience and portfolio of work steers her organically towards memoir, essay-writing, journalism and reviews. On her writing to do list are more submissions and a blog; her TBR pile is ever-expanding. She is new to social media, but still into music, and a keen photographer, into pre-loved stuff and mental wellbeing, she is proud to have recently become a Litro contributor. Links to stories; http://www.paragraphplanet.com/jan1621.gif https://www.fridayflashfiction.com/longer-stories/birthday-days-by-barbara-wheatley https://www.fridayflashfiction.com/100-word-stories/hand-on-heart-by-barbara-wheatley https://www.fridayflashfiction.com/100-word-stories/on-the-horizon-by-barbara-wheatley https://www.fridayflashfiction.com/100-word-stories/clothesline-by-barbara-wheatley https://www.fridayflashfiction.com/100-word-stories/parking-meter-by-barbara-wheatley https://www.fridayflashfiction.com/100-word-stories/chocolate-box-by-barbara-wheatley https://www.fridayflashfiction.com/100-word-stories/way-to-go-by-barbara-wheatley https://www.fridayflashfiction.com/100-word-stories/potato-cakes-by-barbara-wheatley https://www.fridayflashfiction.com/100-word-stories/about-flash-fiction-by-barbara-wheatley https://www.fridayflashfiction.com/100-word-stories/gone-with-the-wind-by-barbara-wheatley https://www.fridayflashfiction.com/100-word-stories/case-study-body-parts-by-barbara-wheatley https://www.fridayflashfiction.com/100-word-stories/hope-by-barbara-wheatley http://www.paragraphplanet.com/jan1621.gif https://www.fridayflashfiction.com/100-word-stories/postcard-news-by-barbara-wheatley https://www.fridayflashfiction.com/longer-stories/come-home-by-barbara-wheatley https://www.fridayflashfiction.com/longer-stories/oh-potter-by-barbara-wheatley