You have no items in your cart. Want to get some nice things?

Go shopping

I came across the photographs as I was helping my aunt unpack into her new house. She was finally beginning to let go of my uncle, who had died eight years prior of a heart attack, in the middle of the night. Or at least she was outwardly navigating her life so that the grief didn’t permeate her every word and action anymore. He was a quiet, hardworking man, who owned a law firm and didn’t say much, but always danced at the family parties. I remember talking with him when I was little, telling him about the troubles I was facing in my third-grade love life.

I said, “I don’t know what the problem is. I’m casting my lines out but not getting any bites!”

He paused and then coyly said, “Well, maybe you just have to change your bait.”

My aunt, who used to be loud, dramatic, and the life of any party, was never the same afterward. But her house was: the beautiful two-story with high ceilings, exposed brick in all the right places, a few blocks from my childhood home. I remember being a little kid, spending the nights on her couch eating ice cream and watching TV shows my mother would have baulked at, screaming curse words and giggling just because I could. That was who she was.

I was devastated when she decided to sell the house, as we all were. It was the only house left where we had consistent holidays, after everybody started extricating their lives from one another’s and spreading apart, in all senses of the term – phone calls replacing the nights spent together, dancing around the living room to Sinatra records, laughter rising up to those high ceilings. I had been long gone when she sold the house and moved into the new one, but just home for Christmas Break from school, when we decided to go to New Orleans for New Year’s. The new house was small, quiet, filled with light and windows, with pretty white walls and furniture. Oddly enough, it was even closer to my childhood home: you could see it in the distance if you stood just so, on the intersection in the middle of the street. I pretended to go grab something out of the car a few times that day, just so I could stand and look.

There was a purple bike slumped over in the front yard: the purple bike I left behind from my childhood for the little girl who was about to move in, all those years ago. I couldn’t believe it was still there – it was almost too perfect. I didn’t know anything about the family who was living there now, or the inhabitant of the room where I grew up. Just like I don’t know much about the person who resided in the room I sit in currently before me. There’s something so curious, yet so commonplace, about the idea that we truly don’t know anything about anyone. The world is filled with far more strangers than people we will know. Perhaps this knowledge was teeming in my brain as I started looking through the photographs that afternoon. I know I wasn’t being helpful as my other relatives hauled boxes and chairs, but some things are objectively more important. I said I’d go through them just to be sure nothing important got thrown out.

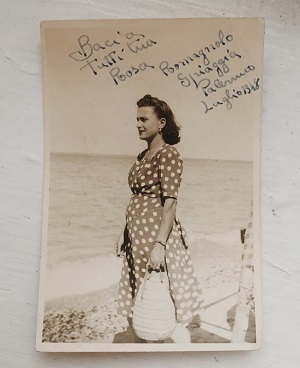

I was told they were from my uncle’s grandmother, who had immigrated from Italy. The photographs were tiny, four-by-three black and white photographs of strangers, ostensibly family members, young and old. Quite a few of two young boys, tanned and smiling, fighting with fake swords in the street. One of a little baby, an unlit cigar stuck in his mouth, and another of the same little boy in a hat, under the sun, sitting next to a golden retriever. In ink on the back are the dates, ranging across the summer of 1949. I took several of them home.

My favourite features a woman standing, her hair blowing in the wind, in front of the sea. She wears a long, polka-dot dress, with a soft, yet apprehensive, smile across her face. The ink, this time scribbled across the front of the photo, reads, “Baci a Tutti Tua Rosa.” Google Translate told me this meant “Kisses to All,” signed by “Your Rose.”

“Do you have any idea who this is?” I asked my aunt.

She didn’t. And anybody who would’ve had a clue was long gone. I kept the photograph in my wallet for months, until I moved into my current apartment, and put most of the photographs up on my wall, filled with letters from friends and family. Rose lives next to an envelope from my Dad, that says, “To My Girl, Love You More.” I wonder who she sent the photo to – who were the recipients of the kisses? I wonder, if I misplaced the envelope someday, whether someone would ask the same question of my father. But beyond this, I wonder if anybody cares, or if Rose thought somebody would care. Because here, seventy-two years later, I marvel at the fact of this woman’s existence, and I want to write about her, having never known her.

And I think about the essence of the billions of lives lived without our knowledge or awareness: the understanding that this is not The Truman Show, and that people are not characters and people exist, time after time, outside of the realm of your consciousness. There’s something so comforting, yet so terrifying, about the prospect of your own existence being perceived by those you have no awareness of. But there’s also the terrifying possibility that it will not be: that your pictures will be thrown out with the dust, or that your letters will not be stuck to someone’s walls.

Because I’d be willing to bet Rose, wherever she is, wasn’t expecting to be written about here, by someone she had never known and will never know. Have I intruded on her legacy in some way? I can’t say. But I know that if one of my letters or photographs ended up in a shoebox, transported from a space of a stranger to the space of another, and that placing it upon a wall would grant some semblance of peace or familiarity to the individual residing in the borrowed space, I would be honoured. To think that my life in all of its foreign-ness had contributed in some way to the connectivity of being human.

But then there’s the inevitable day you take the picture down. That’s just the thing about living and leaving our homes, these spaces, that are necessarily liminal. Even if by some very slim chance or stroke of luck or whatever it might be, you return to live in the same unit, same building, again, it is impossible for it to be the same time period, the same era of the lifetime, the same cast of characters. The wanting to hold onto it leads you to miss things you never ever thought you’d miss, that are even downright silly to miss, like the walk to the trash bin along the side of the building, the way the light falls across the fence, the little piece of paper with your name typed on it that goes inside the pocket on the outside of your mailbox, that your friends will never buzz your door again, or the parking lot of the elementary school next door, where that kid came up to you with the purple flower, asking you to be his Valentine. You return your keys and, unlike other places where you know you’ll return, or other people who you know you’ll see again, there is an absolute finality and required acknowledgement of the passage of a certain period of time, of life gone by and days forgone that you’ll never again have. And whether it’s a happy departure, or a necessary departure, or a combination of any reason, there’s something especially striking about the ability to say, on this specific date, the chapter ended.

But how beautiful it is, in spite of this, that we have letters and photographs, bicycles, from those who are strangers and those who we think we know. That we can inhabit homes, rooms, lives of one another, and have these artefacts to remind us that life is worth something: how much you seek to walk through and plant this feeling of knowing and being known – maybe even loved – in those of others.

–

About the author:

Gabrielle Dufrene is a poet and writer of creative nonfiction; she is currently in the Creative Writing MA program at University College Cork in Ireland. She is originally from the American South, and her work often focuses on the interactions between religion, sexuality, place and acceptance.

Gabrielle Dufrene

Gabrielle Dufrene is a poet and writer of creative nonfiction; she is currently in the Creative Writing MA program at University College Cork in Ireland. She is originally from the American South, and her work often focuses on the interactions between religion, sexuality, place and acceptance.