You have no items in your cart. Want to get some nice things?

Go shopping

This is an unusual novel. As the title suggests, this book takes the readers to a particular location, elaborately described. And as hinted at in the title, this short novel demands space and time. It requires a willingness to change pace and perspective, to turn off the constant noise of everyday life and to follow the grandson of Prince Genji in his quest to find the most beautiful garden in the world.

The plot is scarce, almost non-existent. The grandson of Prince Genji lives outside time, across centuries, and yet he disembarks from a train and climbs up a hill, through deserted streets to visit a monastery. Everywhere there are signs of human presence, but he is alone. A group of men, his retinue, are late to follow him and fail to find him. The omniscient narrator shares with the readers one short dialogue between these men and an old woman in the town, and a close look at some other living creatures, recently or soon to die: a battered dog, a rabid fox, and thirteen dead goldfish which were nailed to the side of a wooden hut.

Although dotted with these signs of violence, decay and suffering, the empty monastery, with its paths and gardens, buildings and shrines, is a monument of beauty. The narrator’s gaze is slow and focused, describing what is there, but also informing the readers of how it came to be. The compound, like the world in which is exists, is a product of careful, calculated and laborious planning. Nothing is accidental and the beauty is the result of a study of symmetry and the properties of objects. This is true of the man-made artifices, and this is also true of the natural world in which these structures stand.

The narrator takes pains to look closely, and then to analyse and to describe. Nothing exists in a vacuum, and the novel, made up of short chapters, can be read as a catalogue of the underlying and overlapping structures that make up the monastery, and the experience of it. The physical and the metaphysical combined.

The all-seeing, all-knowing voice of the narrator is serious and uncompromising, but from the beginning, the author gives the readers options as to how to relate to this novel, how to decode this omniscient voice. The novel opens with a precise location that is – and at the same time, is not – there, the ancient but no longer existent, gate Rashomon in Kyoto. The subject of a short story by Akutagawa and immortalised in Kurasawa’s film of the same name, the Japanese word Rashomon means “dispute” and is the name of a gate with three entrances, suggesting the necessity of alternative truths. Even when the world is emptied of people and their prejudices, when the physical world is described and dissected to its barest elements, meaning remains allusive, even the Buddha himself does not offer a straightforward answer.

Inside the monastery is a small wooden statue of Buddha.

He was motionless, he never changed, he had stood on that same point for a thousand years, always in his place, in the exact middle of the inordinately secure, gilded, wooden box, he stood imperturbably, always in the same robes, always frozen in the noblest of gestures, and during that one thousand years nothing had changed in the carriage of his head, in the beautiful, famous gaze: in its sadness, there was something heartbreakingly refined, something unspeakably noble, his head turned away from the world most decisively. It was said about him that he turned his head away because he was looking backward, to the back, toward a monk known as Eikan, whose speech was so beautiful, that he, the Buddha, wished to know who was speaking. The truth, however, was radically different, and whoever saw him immediately knew: the Buddha turned his beautiful gaze away so that he would not have to look, so he would not have to see, so he would not have to be aware of what was in front of himself, in the three directions – this wretched world.

In all directions there is pain and beauty to behold and the prose, like a slow cinematic lens, pauses to allow the readers to take it all in. The language is powerful, using long descriptive sentences and the English translation is rich and captivating, almost mesmerising.

And just when the readers can be caught off guard, taken by the poetry and the flow of this unique and commanding narrator, the author breaks the spell by describing another, fictional, ambitious metaphysical book, The Infinite Mistake by Sir Wilford Stanley Gilmore. This composition is a pseudo-mathematical proof that the world is finite. The long and detailed verbal description of a book that consists of numbers, seems to mock the readers and try their patience. While it is the fictional author that is unconventionally rude in his introduction, it seems like the readers would join him in swearing. Here, the mere experience of reading can take different paths.

In the middle of the novel, half-way through his journey, the grandson arrives at two impressive buildings, the two halls containing the treasures of the monastery: its riches and its sutras. Rather than describe the content of the sacred scrolls, the narrator describes their physical genesis, from seed and plant into paper on which the teachings are written. The truths contained in them are also part of a manufacturing process by which the natural world becomes man made, like the rest of the compound described in this novel and like the novel itself.

The novel is the story of a quest, a centuries-long search for the most beautiful garden. Interestingly, the process by which this garden comes to exist is the exact opposite of the creation of books, the religious sutras or Krasznahorkai’s novel. The garden first appears in a book, and then in the mind and the imagination of the grandson of Prince Genji who has read the description of this garden in the book. He then sets on a mission to find it. The book is lost, the verbal and ink made description gone forever, and yet the imagined garden can become a seed and grow and bloom. It is hidden, because its beauty is in its uselessness. It is marginal, “something of no interest.” And perhaps this is true of the novel itself. The plot is trivial, the wandering in the compound of this deserted monetary is meaningless and the signs, symbols and clues hinted at throughout the novel do not reveal a thing. The novel simply is. Give it the time and attention it deserves and it will stay with you for the rest of your life.

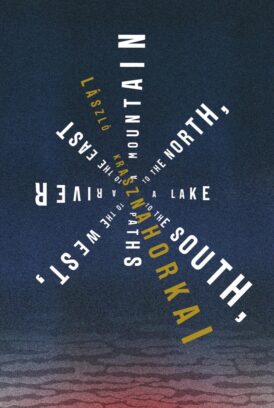

A Mountain to the North, a Lake to the South, Paths to the West, a River to the East

By László Krasznahorkai

Translated from the Hungarian by Ottilie Mulzet

New Directions, 144 pages

Tamar Drukker

Tamar is a lover of words and languages. She completed her PhD at the University of Cambridge and have written on the readers of Middle English manuscripts and on chronicles. She has taught Hebrew and Israeli Studies at SOAS, University of London for over 15 years. She is a freelance literary translator and would happily spend all her days reading.