You have no items in your cart. Want to get some nice things?

Go shopping

Crime is deliberate, causing physical or psychological harm and damage to people and property, and is illegal. Where there is crime there is punishment. And where there is a perpetrator there is a victim. This also manifests curiosity and speculation. Moving oneself out of a comfort zone, to immerse oneself instead in an underworld of Chinese crime only to lose oneself there. But can crime be different the world over?

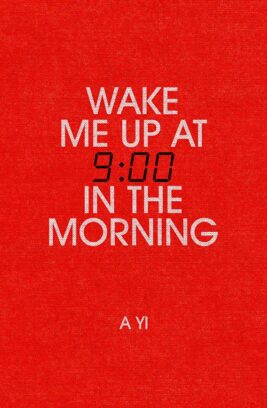

Theft is the most popular crime and indeed it is theft that features heavily in this novel. Behind the simplest of red covers and title fonts, the author of Wake Me Up At 9:00 In The Morning, A Yi, is already noted for his “unsentimental world view” and “challenging literary style.” His style can seem a bit weird, but it works – it is fine to mix existing genres, and to cross borders in genre, in order to create something new. A Yi has, however, taken it further to produce something experimental. Will most readers have ever read anything similar? Probably not. In his choice of characters, who are members of clans, (including the Ai), setting (rural life in an Aiwan countryside and village) and time period, A Yi has combined elements of what he loves with his own life and work experience. Book review writers would find this novel both intriguing and refreshingly unconventional.

Interestingly, the novel started life three years ago and is available in Italian and Chinese, which makes me wonder about the translation of a translation of a translation and how different the telling might be. Here we have a male author and a female translator and together they have constructed the novel to greatest possible effect. A Yi is part of a literary set and takes his writing very seriously. He was inspired to write Wake Me Up by the bleak view of humanity he witnessed in his career as a detective. Under the pen name A Yi, he is best placed to describe crime and re-enact it in the pages of a novel. We as readers likewise play detective and aim to work things out for ourselves, joining dots and spotting clues of which there are almost too many. At times, perhaps, the imparted knowledge of a detective in his first full length novel is not so easily transferrable to a reader. Moments in time are played out meticulously moment by moment. It’s what you don’t see or read that is more telling, hence the need for joining dots.

My interview with Nicky Harman, the prize-winning translator of this novel with 25 years of Chinese contemporary fiction behind her, is a joy and a privilege. She explains her top tip – that the accuracy of the translation lies in reflecting the style of the writing. She first considers what is actually being said, and the effect of why it is so. There are multiple things at play because, as translator, she needs to know what A Yi wants to do and say and why, as well as taking on board any sentimental threads. Due to its deliberately experimental style, there are ambiguities that needed to be toned down for the Chinese market as it was far more gruesome in its original form. I am one who loves ambiguity, but it is not clear at times where one character’s voice ends and the other begins, so a little of the impact is lost. Nicky would describe her translation as being “rendered” rather than embellished. She likes to see herself as an “intermediary between cultures” and has “the privilege of showing others what exists in other cultures.” I cannot disagree. As for the editing of the translation, she explains that her editor becomes her best friend.

The characters and place names are perhaps difficult to digest at first, but the beauty of the language is largely due to the translation. Language is exquisitely woven into events with the story being told by several narrators over five sections of the book. A Yi is deft in his creativity and Harman provides us with as beautiful a prose as possible and in this, they become writing partners in crime.

In keeping a man’s notoriety alive (despite being found dead by his lover), we are invested from the start. At the funeral of chief mobster Hongyang, circumstance and action come at once. Tastes and smells abound as does touch. The event becomes an opportunity for characters and community to come together, although not necessarily out of respect for the deceased, and get caught in the hustle and bustle (where it is described as “a herd of migrating water buffalo”) whilst being given a chance to say their piece.

Is there a longing for connection? In the sense of community, of village and non-fictional village life, yes, as it is brought to the surface through humanity, death, marriage, family, camaraderie and loyalty. But the novel makes a huge emotional impact on the reader with issues of criminalisation of gang members and women, prostitution, vice, greed, addiction, respect, disrespect, trickery, corruption, debauchery, lies, money, and revenge. A Yi hereby showcases humanity not only at its best but also at its worst. As a female reader I was particularly drawn to the misogyny which is rife. Were the novel to be written today it may, perhaps, be different, given the progress society has since made. It is also written pre-pandemic, so again might look different through a post-pandemic lens.

The novel is indeed graphic in its detail, but it needs to be, to properly portray the underworld scene. The author is clever, however, at knowing the limits, and often despite the minutiae, elements are skilfully left to the imagination through layered detail. Better still, with the advent of cult viewing such as “Parasite” and “Squid Game,” or Spain’s “Money Heist,” there is a feeling that this book could quite easily become cult reading and viewing itself. Think also Brett Easton Ellis’s “American Psycho.”

The story is also driven by obvious conflict. Whether internal or external, it is how A Yi brings his tale together. The very opening line, set in the present day, “Xu Yousheng was to hear a lot more about Jin Yan when he arrived in Aiwan” immediately places the reader at the heart of an internal conflict.

Quite early on, the book title begins to make sense. There was a controversial reference to Jorge Luis Borges being behind the original title. A Yi himself tells me that the novel was originally called “Mud and Blood,” which is a metaphor for a person’s filth and cruelty. The title eventually used, although reasonably bland, does nonetheless imply an ending – that the protagonist does not wake up as expected. It was inspired by the phrase in a Borges dialogue with his rival Sabato, where they talk about what’s real and what is a dream. But it was also based on a tale heard by A Yi’s friend at her grandmother’s house about a man who had died drunk, which is not that uncommon an occurrence. Pitching this whodunnit with an ambiguous title works; the tale is thereby still unexpected. As Nicky Harman says, “the difference is that there is much more than crime in A Yi’s stories, but they do all contain crime.”

A Yi cleverly processes information into short stories first. Is it A Yi’s real world? Has he created a superficial reality? Does anyone lead a normal life? What is external happiness and duty, and what is domestic happiness? Power is at play – followers, subordinates, enemies, supporters, rivals, schemers, family and friends all make up the community which A Yi created and which the character Hongyang made and leaves behind. Hopefuls are in line to try to take over from him and almost re-position themselves within the community to do the same or different or better – or worse – but there is clearly only one Hongyang; I believe the community to be spherical in its existence. “Hongyang had looked daggers at you, even as a little kid. A person like that was born once in a generation.” Nicky Harman confirms there was always some good to be found in Hongyang – despite the dirty dealings.

Symbolism, philosophy and mythology form a huge part of Chinese culture and feed the writing of each chapter. The Underworld referred to is not the afterlife, although, in Chinese mythology, there are 18 levels of hell (which reminds me of a staircase in ascending or descending order of seriousness of a crime). How many crimes have been committed exactly? They are interlinked, interwoven and countless, committed one within the other.

Upon investigation and closer inspection, the nucleus of the story lies dead centre of the book, although it’s possible not to approach the novel as a whole, due its complexities. Chapters 17 and 18 for example are deliberately self-contained, in which a psychopathic waitress goes on a killing rampage. This supports A Yi’s preferred method of writing in short story form first. He got the idea from working magazine journalism where effectively a supplement was stapled to the middle of the magazine. The creativity to resemble what he knew by inserting such an idea is nothing short of genius. It further explores the writing form and pushes boundaries, creating something entirely conceptual.

Reading this novel calls to my own mind some kind of omniscient mind map, with landscape, characters and crimes carefully plotted. Within each description there could well be a clue. We ask ourselves who’s connected to who, which explains the need for a character list, that reads like a screenplay, and not just in terms of family or friendships. In this mind map chapters 17 and 18 are at the centre and everything explodes outwards from there.

One scene stands out for its descriptive scene setting and could resemble the likes of a gamblers’ den found more typically in gangster films:

“The chandelier looked like an anchor. The lamp base …. spray-painted to look like it belonged in a European country house. It was lit by six coffee-shop-style bulbs, each emitting a warm golden glow like everlasting candles, and Hongliang* often raised his tall, amber-stemmed glass …. sipped his brandy, to the accompaniment of Fleetwood Mac on the sound system. The vocals…. gradually eclipsed during the song as the instrumental took over, making you feel weightless, as if suspended over a waterfall.”

* Hongyang’s cousin

Take note of the double-entendres here, of the imagery, simile and metaphor, because they recur throughout the book. The scene links the reader to a more popular European setting rather than one that is culturally Chinese. The novel, however, has its own defined sense of place and showcases Chinese human nature. It is greater than the sum of its gruesome parts. There is irony in something so gruesome being described so beautifully. Violence, Harman explains, is difficult to deal with, so one learns to step back and put any personal feelings on a backburner to re-address later. Wake Me Up points out that “we all know that every event has one outcome but many causes.”

I undoubtedly ask questions of this novel, but one thing is certain: I will not look at Chinese culture the same way again. As a reader it has been put on my map and perhaps that is the whole point. It becomes more of a popular manifestation, mentioning for example yin and yang (opposite but interconnected forces – and maybe no coincidence that a main female character has the name Jin Yan), and feng shui. Even the featured mah-jong tile-based game is used as metaphor for “following the rules of the game of life.”

Ultimately this is a policeman with a story, wearing a journalist’s hat, an amalgam of fictional and non-fictional experiences and it is the continued fascination of wanting to go back to pages in case you’ve missed something – to check back on detail or to find a missed clue – that make the combination so powerful. Unlike its opening, the book has a more open-ended closing sentence, leaving us with another dot to join.

Wake me Up At 9 In The Morning

By A Yi

Translated from the Chinese by Nicky Harman

One World, 416 pages

Barbara Wheatley

Barbara has a longstanding passion for language and the written word. A reader who writes, and a writer who reads, she freelanced her way in London for 8 years in PR, writing promotional campaigns, press releases, copy, slogans, etc., within the music and entertainment industry. She last promoted PR packages within the Press Association before full-time motherhood allowed Barbara to pursue her interest in Creative Writing. This creative enthusiasm led to 3 unfinished fiction novels. Now a mum to 3 teens, she has been a student on college and university courses as well as workshops and festivals, independently and online. A move to Devon saw her first flash fiction submission longlisted then shortlisted. Her work has regularly been published on Friday Flash Fiction (which also appears on Twitter) and has appeared on Paragraph Planet and several collections of new writing. In the pursuit of her true writing voice, she concentrates nowadays on Creative Non Fiction, where her experience and portfolio of work steers her organically towards memoir, essay-writing, journalism and reviews. On her writing to do list are more submissions and a blog; her TBR pile is ever-expanding. She is new to social media, but still into music, and a keen photographer, into pre-loved stuff and mental wellbeing, she is proud to have recently become a Litro contributor. Links to stories; http://www.paragraphplanet.com/jan1621.gif https://www.fridayflashfiction.com/longer-stories/birthday-days-by-barbara-wheatley https://www.fridayflashfiction.com/100-word-stories/hand-on-heart-by-barbara-wheatley https://www.fridayflashfiction.com/100-word-stories/on-the-horizon-by-barbara-wheatley https://www.fridayflashfiction.com/100-word-stories/clothesline-by-barbara-wheatley https://www.fridayflashfiction.com/100-word-stories/parking-meter-by-barbara-wheatley https://www.fridayflashfiction.com/100-word-stories/chocolate-box-by-barbara-wheatley https://www.fridayflashfiction.com/100-word-stories/way-to-go-by-barbara-wheatley https://www.fridayflashfiction.com/100-word-stories/potato-cakes-by-barbara-wheatley https://www.fridayflashfiction.com/100-word-stories/about-flash-fiction-by-barbara-wheatley https://www.fridayflashfiction.com/100-word-stories/gone-with-the-wind-by-barbara-wheatley https://www.fridayflashfiction.com/100-word-stories/case-study-body-parts-by-barbara-wheatley https://www.fridayflashfiction.com/100-word-stories/hope-by-barbara-wheatley http://www.paragraphplanet.com/jan1621.gif https://www.fridayflashfiction.com/100-word-stories/postcard-news-by-barbara-wheatley https://www.fridayflashfiction.com/longer-stories/come-home-by-barbara-wheatley https://www.fridayflashfiction.com/longer-stories/oh-potter-by-barbara-wheatley