You have no items in your cart. Want to get some nice things?

Go shopping

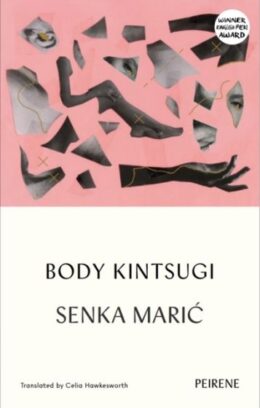

You begin reading a novella by Senka Marić called Body Kintsugi. You are already intrigued by the book’s blurb, which describes this slim aesthetically pleasing volume as a “powerful and personal novella.” An interesting categorisation. You wonder, will this work be fictional, fragments from real life embellished, or completely truthful? How would you know anyway, without sneaking a look at Wikipedia or Google? No, go in unknowing. You know it’s better to read this way.

So you begin, engrossed within a few pages that switch, episodically, between a now and a then. A to-ing and fro-ing of the narrator as a young girl growing up in Bosnia and the present day, narrated by a woman soon subsumed by the medical world when she discovers a lump in her breast.

What is immediately arresting is the use of second-person narrative, which Marić maintains throughout. This is a very specific choice for a deeply personal work characterised by brushes with death, excruciating pain, and an illness many of us hope never to experience. Marić’s voice is controlled and places her, as the author, a degree apart from her narrator. This narrator, in turn, tells her story by projecting it onto the reader through a ‘You’ that has experienced all of these events. This is your life for 165 pages. The layers of separation between reader, narrator, and writer may, in less skilful hands, be alienating, but Body Kintsugi is an engulfing read.

As is the case with many readers who are chronically ill or disabled, when I became sick I went in search of narratives that I could see myself in. Over the last decade, I have discovered personal essays, short stories, poetry, and paintings that have become common lore amongst online unwell peers. When reading Marić, Anne Boyer’s The Undying and Audre Lorde’s The Cancer Journals immediately sprang to mind, given these three writers’ experiences of breast cancer. Yet Body Kintsugi is a different reading experience altogether given its narrative technique and dream-like episodes. The world evokes Maria Gerhardt’s Transfer Window, another short but impactful read of a woman in a seemingly utopian hospice in Copenhagen. Told in vignettes addressed to a lover, the autobiographical becomes worldbuilding material in a moving account of “my body, of memories, of the person I used to be. The person I will never be again.” As Marić tells us, “This is a story about the body. Its struggle to feel whole while reality shatters it into fragments.” To experience life-altering illness, her title implies, is kintsugi – to be shattered and remade, bearing the scars that become structurally intrinsic because they mean survival.

In many autobiographical illness narratives, the author keeps events as close to reality as possible. The discovery, diagnosis, and treatment happen in a linear arc, lest the audience’s belief wavers. Marić’s faith in the reader pays off as she diminishes the gap between the reader and her narrator’s, uniting them as one ‘You.’ Here, there is no room for the othering of the sick or removed sympathy towards a first-hand account. Rather, the reader is tied to the events as they unfold, intimately undergoing the same alienation from the body and self as the familiar is transformed into an unknowable, dangerous site. You have no choice but to go along for the ride.

Marić intersperses the narration with four medical documents, detailing a diagnosis and three subsequent treatment plans. This introduction to medical language illustrates how the sick have to become fluent in a discourse that is far removed from their native tongue. Not only this, but the sick also experience being reduced, in medical settings, to the documents that code their conditions and guide their ability to request decisions based upon this status: “The document that holds the secret of your cells convinces her.” This is a reminder that exceeds ideas of empathy, rather, it is the replication of the medical sphere’s search for empirical evidence. In this cause-and-effect world, things are clear-cut. In moments where the source of pain or sickness has no detectable cause, such narratives, however objective they sound, can readily be dismissed, delaying essential treatment. This is something Marić’s narrator experiences early on, when “the doctor said all you could do was take painkillers and wait for it to pass.” Soon after this, by chance almost, she sees her radiologist outside the hospital and, frantically explaining the situation, is asked to visit him in the clinic. In a matter of days, she is diagnosed with carcinoma in her breast. Illness is universalising when you become sick, Marić reminds us. No matter who you are or were, or how powerful you may or may not be, at the centre of it all: “You are just a body.”

Of the many themes that Marić touches upon, the struggle of occupying and living in a female body is a uniting thread between the narrator’s past and present self. As the younger narrator experiences her period, and the unusual levels of pain many of us are told are ‘normal,’ she reflects, “You become aware of how difficult this transformation, this turning into the body of a woman, is going to be.” Through evoking Simone de Beauvoir’s famous line, “One is not born, but rather becomes, a woman,” Marić impresses on us that not only are these physical realities traumatic and painful, but the way in which society reduces, normalises, and shames women for them is equally harmful. The use of second-person narration forces the intensity of women’s pain and shame onto the reader, which bleeds into every arena the speaker enters, be it social or medical settings. More than once, I had to put the book down because it was more than too close to the bone, rather, the very marrow of what so many gendered bodies experience. Her descriptions of pain are explosive and evocative, a visceral reminder of how pain can whiteout everything but itself. She spares the reader what so many narratives do, which is a welcome intervention that allows pain to be just what it is, without having to transform it into a teaching moment that speaks of the value of suffering.

Marić also uses medical reports as markers of the time that is passing throughout her cancer treatment. Time becomes a liminal space when you’re sick. How much time do you have left? How long until the painkillers start working? How long do you have to endure these nauseating treatments? “Time has no meaning. Its passing is measured in therapies, not minutes.” The strong painkillers and treatments that the narrator undergoes introduce slippages and lost time. As Carolyn Lazard writes, “My sense of self as a subject in a particular time and a particular place evaporated.” Not only this but, during these dream-like moments, a more mystical world emerges. A space for possibility, and escapism from the drudgery of managing illness.

In multiple episodes throughout the text, the narrator is visited by apparitions of women while in bed. Sometimes of these are famously wronged women throughout history, such as Medusa or Medea, which resonate with the deep-seated shame forced upon her body as a child. Others are vaguely familiar figures with whom she communes. These episodes, for me, evoked surrealist Leonora Carrington’s mythical worlds rendered in her autobiography Down Below, the witty, illuminating novel, The Hearing Trumpet, and her paintings – particularly Adieu Ammenotep (1960). Here, the subject is surrounded by cloaked women in white and black performing some kind of operation. These ghostly, yet comforting figures tell Marić’s narrator, “We’re your ancestresses… Your pain is inscribed in our cells, while you carry ours within you. Others will come too. To teach you.” To live with pain, the narrator realises, is an inherent part of womanhood. The solidarity in these shared experiences gives the narrator strength to continue, bolstered by a world unseen, in these recurrent lyrical moments.

Body Kintsugi is a triumphant novella for many reasons, but particularly because Marić resists the restitution narrative, the neat resolve bringing a story to a close in the simplistic ‘yesterday I was healthy, today I am sick, tomorrow I will be healthy again’ (Frank, 2013). Rather, the novel in a dreamy way, marries her childhood memories with realities. It isn’t a case of ‘was sick’ and ‘is no longer sick’, but something that, effortlessly, transcends the banality of categorisation. Instead, Marić’s version of kintsugi says, look at all the things you have been through. You are still here, despite it all, and you have the scars to prove it.

By Senka Marić

Translated from the Bosnian by Celia Hawkesworth

Peirene Press, 168 pages

Jennifer Brough

Jennifer Brough (she/they) is a slow writer and workshop facilitator based in Nottingham. She is working on her first poetry pamphlet, Occult Pain, which explores the body, pain, and gender through a magical, disability justice lens. She is also the founding member of resting up collective, an interdisciplinary sick group of artists that offers workshops on rest and creativity. Find her on Instagram @occultpain

- Web |

- More Posts(6)