You have no items in your cart. Want to get some nice things?

Go shopping

The bride wore a satin gown with an open draped back. Estelle saw the birthmark on the bride’s left shoulder. She saw it, as the bride passed her, walking up the aisle, Estelle saw it close. Unmistakable. Against bridal white. Her hand shot to her mouth to cover her gasp. Rose. Rose, the baby she gave up twenty-seven years earlier, had the same black crescent birthmark.

*

Estelle met Rose a week earlier at a small supper given by the bride’s godmother, Charlene. Estelle thought the bride handsome, a face of angles, lightened by steel-blue eyes, framed by long tawny hair. She spoke in a drawl leavened by education in the north. Rose made Estelle talk about herself. Not something she normally did with strangers. Estelle confessed to spending all her time and most of her money on books. She was reading It Can’t Happen Here by Sinclair Lewis, about the possibility of fascism in America, and recently finished Colonel Lawrence by Liddell Hart, a solid man, a life rudely told. Rose had read those books. And the two found, to their delight, their judgments on the subjects in unusual harmony. They moved their chairs closer and leaned into one another. Parting, they took one another’s hand and kissed. A rare young woman, Estelle thought. This supper with her best friend and goddaughter came off as Charlene hoped. She had intuited like-mindedness and empathy, correctly.

Charlene, a war widow, had come to Columbia, Kentucky from Louisville in the mid-1920’s to become Adair County High School principal. Louisville is where Charlene knew Rose and her parents, Anne and Reverend Henry Stringer. Anne died when Rose was in high school. A few years ago, Henry became pastor at Columbia Presbyterian.

*

Estelle regretted she had to leave the church as the service started. Decorated as she had never seen it. Arches of pink roses the length of the aisle with a pink satin carpet for the wedding party. Intertwined candles and roses, rising like wings on each side of the altar.

She would not be comfortable if she were there, if she had to face them, when the minister asked, “Does anyone know of any reason . . .”

She might have walked up to the altar and said, “This girl is my daughter. That man, there, is the father of the bride.” But, in difficult situations, she found it hard to say what she wanted.

That man, there, in the first pew, on the right side of the aisle, was father of the groom. He was the father of the bride and the groom. George. He had acquired the veneer of money since she had known him. A florid face, a tight shave, a shiny dome, and 20 extra pounds. But she knew his low-set ears and the tilt of his head.

George had been born in this town. From a broken home, he had run the streets, but learned to dress, to talk, to look good, even when doing bad. Muscle for Jesse Jacobs. Jesse would make you a loan, find you a car, provide you pleasant company, anywhere in Adair County.

Estelle slipped out of church so as not to disturb the ceremony, so the others would not miss her, not Reverend Springer, not Charlene.

She persuaded the limo driver to take her into town. The temperature had climbed into the 90s. “The ceremony will last another 30 minutes. You will have time,” she said, and gave him a dime tip.

She sat in the back seat of the car, a Packard, 1935 model, with an oval side window. I told myself back then, I’ll never see her again, if I do, the birthmark is how I will know her, know my baby. She looked back at the church, studied it, and turned away, before the chauffeur drove off.

*

Estelle gave up her baby with considerable reluctance. Her affair with the baby’s father had been a long one, and despite George’s reputation he had been a generous and considerate suitor. She’d even had hopes. But when she became pregnant, he refused to support the baby or her. He tossed her $20 and left town. He would not get stuck in a two-bit burg with a wife and kid.

She had been a salesclerk at Woolworth’s cosmetics counter. She had no choice about the baby. She could not support it and had no family to lean on. She was not told the name of the adopting couple. Better she did not know, the agency said. No fuzzy boundaries that way. For months after, she walked to the park after work. With no one around, she leaned into the heavy willow by the pond, and wept. Later, she went to night school, and landed a steady job as bookkeeper for Champion Construction, a regional builder.

*

Estelle read about the wedding in the newspaper. The paper said the groom and his family were from New Orleans. So that’s where George went. The groom graduated from Tulane and worked for an investment bank in New York. The groom’s father was president of Whitney Bank. The groom’s mother was president of the board of the New Orleans Museum of Art. The paper said Rose graduated from Yale Law, now assistant DA in Manhattan. My baby did well, she thought. And she is smart. I do not know if I could have done so well by her. But Charlene’s supper was more than I’d ever hoped for. To see her, a young, thoughtful educated lady, with a prestigious job. To touch her, to kiss her. My baby.

*

Estelle didn’t sleep. For two days and two nights her brain burned. Finally, she called George. “Are you going to tell them?”

“I am not, you have no proof. You’re making this up,” he said.

She said she had pictures and a birth certificate and, the birth mark.

“I did not sign any certificate.”

“Parents don’t, George.”

“And if you say anything Estelle, you will regret it, I swear.”

Estelle froze in fear. She did not know what to do. She wanted to talk to Charlene, but her friend was out of town. Then the new school year started, and Charlene was busy day long.

A month went by, Charlene told Estelle that Rose had a miscarriage. The couple had gotten a head start. The embryo had a severe heart defect. Rose and her husband sunk into despair. Rose came to town to be with her father, for consolation and healing.

*

Estelle called George, father of Rose, father of Rose’s husband, pillar of New Orleans society. “Now will you tell them?”

“Your crazy story,” he said.

“Think of your child, your children. Think of your grandchildren.”

George shouted, “Have that stain on my family. We are not white trash!”

“Then I will. They must know,” she said.

“Do not do that.” George banged the phone down on his desk.

Estelle would talk to Rose and her adoptive father, Henry, on Sunday, after the service, in two days. She was determined. She would do this.

*

Charlene did not see Estelle in church on Sunday and went to her apartment. A knock and no answer. She turned the knob, the door opened. She found Estelle’s body tossed across her bed like a rag doll. Bruises on her arms, around her throat. The next day, the newspaper carried the story on its front page.

Rose was shaken when she read the news. The woman with whom, even if for such a short time, she had felt such a bond, she would never see again, never talk with again.

Charlene asked Rose a favor, “Investigate.”

“I can’t, it’s out of my jurisdiction,” Rose said.

“For me, honey.”

Next morning, Rose walked into police headquarters. At the entrance, a policeman sitting at a desk. Behind him, a large room with desks and men. On the walls, a U.S. flag, a Confederate flag, the Kentucky state flag. “May I talk to the detective in charge of investigating the Davis murder?”

“That’s Matt Schmidt, over there.”

Schmidt, a large man, square jawed, wide bright eyes, she felt saw everything clearly. She admitted she probably could not be of much help. She did not know the territory, but as Assistant DA in Manhattan, had worked some criminal investigations. The victim, Estelle Davis, was a friend of her father and godmother.

He reached out and cradled her outstretched hand in his palms, “Real mystery to us, ma’am, any help would be useful.”

*

The door to Estelle’s apartment was not forced. It had not been locked. Estelle knew the killer. They walked into a living room wallpapered with scenes of the English countryside and with four tall overflowing bookcases. As her eyes swept the book titles, Rose felt a pang. We would have talked for days. In the bedroom, Van Gogh prints of children, Baby Marcelle Roulin. The killer wasn’t searching for anything. Nothing was out of place. They found a few pictures in the desk drawer. One old photo, faded, blurred of a woman holding an infant. Probably a baby girl, puckered lips, bow in her hair, hand around her mother’s neck. The mother looked maybe eighteen, nineteen. Rose took the photo with her.

That night, at Charlene’s home, Rose asked if Estelle ever said anything about a baby? “No, never. The hospital may have records. Adair County Hospital is just outside town, out on Route 17.”

Estelle Davis had a baby, 27 years earlier. Baby’s name was Rose Marie. Rose Stringer’s middle name was Anne. The father of the baby, George Bridges. Who was George Bridges? They found him in town and school records: son of Mildred (nee Adams) and Fred, parents deceased, graduated from Adair County High, 49 years old now.

*

Rose called her husband. “Sugar, some bad news. No, not about me. I’m fine, ready to come home. I’ve been missing you terribly. But something happened. Remember the woman I told you about, the one I had such a lovely talk with at the supper the week before the wedding, before you came. She was killed. No, no one can figure why.”

Rose explained that Daddy and Charlene asked her to help with the investigation. “It turns out she had a baby, named Rose, like me. The father’s name was George Bridges.”

“Funny,” her husband said, “Dad said when he came to New Orleans, some 27 years ago, he changed his name, to fit in. So, our name is Dupont. He claims we are somehow descended from the original Arcadian settlers. So, he wanted to make it official.”

“Bridges is not a super stretch from Dupont. And of course, your dad’s name is George.” Rose said.

“You don’t think, do you?”

“Not for a second, but we should clear this up while I’m here,” she said.

“Honey, you’re the DA. This is in your court.”

*

Rose told Matt they needed to search the apartment again. Matt reached back in the closet, top shelf, corner, elbow-length gloves, lace handkerchiefs, diplomas, Estelle and Rose Marie’s birth certificates, apartment lease, insurance policy. And more photos, another blurry photo of Estelle with a baby. Baby wearing diapers only. Baby with its back to the camera.

Photo lab at the police station. Blew up the photo. Cleaned it up. Rose was standing between Matt and the lab technician when she collapsed. The baby had a black crescent on its left shoulder. They lifted Rose onto a table and covered her with a blanket. Fire department arrived, oxygen. She regained consciousness. She pulled her sweater off her left shoulder.

Matt protectively bundled Rose into his car and took her back to the rectory. She went straight to her room. “Look after this lady, Reverend.”

Rose looked at the photo again, thought about the so brief, so brief time she had spent with her mother. Rose emptied out.

The next morning. “Daddy, you haven’t told me everything?”

Her father blushed; he took her hand. “You were only a month old. We should have told you. We never knew who your birth mother was, or birth father.”

“Why didn’t you tell me?”

“Mama didn’t want to, made me promise not to, a real thing with her. She wanted to feel 1000% you were hers. She told herself all the time she had spent in labor, and losing so many, there were four before she finally decided we should adopt. You were her baby.”

Henry Stringer also confessed that they changed her birth date to her adoption date and changed her middle name to her adoptive mother’s. Rose sat down, put her face on the table and sobbed. Her father rubbed her back. She swatted his hand away.

Next morning. Rose walked to the park, the pond, sat against a heavy tree. Nothing about me is true. She wept, talked loud, talked low, through lunch, through dinner, into the hour when the swans tucked their necks into their feathers. She whispered Rose Marie. She shouted Rose Marie. Jumped up, strode back to the rectory.

DNA confirmed. Rose was the murdered woman’s daughter, the natural daughter of Estelle Davis. “I am going to find the son-of-a-bitch who killed my mother. And, George Bridges.”

Two days later, Rose walked into the police station. Matt jumped out of his chair to help her in. “You’re alright? Should you be here?”

“Thank you, Matt, but I’m not fine china. Let’s go find the killer.”

“No known enemies in town,” Matt said, “Out of town, who knew her?”

“What about her phone calls?”

One call, two days after the wedding to a number at Whitney Bank in New Orleans. Then, three calls in the last two weeks. Two to the same number. One from that number. Her only calls.

“Strange. My father and father-in-law is president.”

“Say again.”

Rose explained.

“Let’s go see him.” Matt said.

*

Rose called her husband. Told him he needed to hear this sitting down. She explained about her birth certificate and about their father’s name change certificate the police found in New Orleans. “Sugar, I am so sorry,” she said.

He did not understand why.

“It’s about children. We cannot have them, not our own, yours and mine. Can we live with that?”

Her husband balked. Brought up all the inconvenience of condoms. The sloppiness of pull out and pray. “Can we talk about it some more, when you get home?”

“Sugar, there is nothing to talk about,” Rose said. “After what happened with our first one. If we want children, we adopt.”

“I don’t know.” Her husband hesitated, “There won’t be more Duponts.”

“Do you not understand? There never were.”

“What would Dad say?”

“That matters? This is about us. Not him. I’ll call when I get back from New Orleans. In the meantime, I want you to think about this, seriously.”

“Say hi to Dad.”

“We’ll talk when I get back to the city.”

*

“Mr. Dupont, I believe you know that your daughter-in-law is also your daughter?”

The banker blustered and hollered. “Some made-up story from a crazy woman over in that two-bit burg she and my boy got married in.”

Rose patiently explained that George Bridges is the name on her birth certificate and the New Orleans courthouse has a record of a George Bridges, born in that two-bit burg, becoming George Dupont some 27 years earlier.

“And why?” Matt asked, “Did you buy a train ticket from New Orleans to that two-bit burg the day Estelle Davis was murdered, and back the following day?”

Mr. Dupont said he had business in that town. Dinner with a customer.

“You arrived at seven in the evening, left at seven the next morning. Ten hours round trip for a dinner?” Matt said.

Rose and Matt led George down a path that put him in the town, with no customer, “We checked Whitney’s records before coming down here, sir.” And the police had fingerprints from Estelle Davis’s apartment, full prints, probably a man’s, from the size. Not matched yet. And then there were the phone calls. “What were they about, Mr. Dupont?”

“Goddamnit, that woman was about to ruin my family’s name. The time, the effort, the money I put into getting here, president of the biggest bank in town, New Orleans society. I couldn’t allow it!”

*

Rose called her husband. “Sugar, things are not well down here.”

“What happened?”

“Our father was arrested for first degree murder.”

“Why?”

“He strangled my mother.”

“Are you sure?”

“I am sure because I was there when he confessed.”

A week later, Rose’s husband met her at Penn Station in Manhattan. Porters followed her with five sturdy wooden crates.

“What are those?”

“My mother’s books.”

“Where are we going to put them? Our place is tiny. Where are we going to sleep?”

She blew him a kiss as she led the porters to a waiting truck. “Seems we’ll be having a few things to talk about, won’t we, Sugar.”

About the Author: Townsend Walker draws inspiration from cemeteries, foreign places, violence and strong women. A collection of short stories, “3 Women, 4 Towns, 5 Bodies & other stories,” 2018. Winner of a Book Excellence Award, an Eyelands Award, and a Silver Feathered Quill Award. A novella, “La Ronde,” 2015. Over 100 short stories and poems have been published in literary journals and included in 15 anthologies. Short Story Awards: two nominations for the PEN/O.Henry Award, first place in the SLO NightWriters contest. Four stories were performed at the New Short Fiction Series in Hollywood. He reviews for the “New York Journal of Books.” During a career in banking, he wrote three books on finance: “A Guide for Using the Foreign Exchange Market,” “Managing Risk with Derivatives,” and “Managing Lease Portfolios.” https://www.townsendwalker.com/

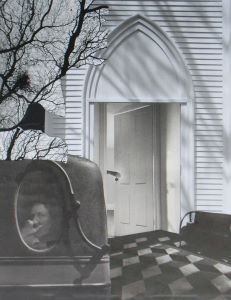

About the Artist: Beverly Mills is a San Francisco based artist; her studio is in Chinatown, her subjects – critical social issues. Her current signature image is noir-influenced original black and white collage, using images gathered from around the world, mostly found, some photographed. She also works in wood assemblage and acrylic on clayboard. https://www.studiobeverly.com/

Townsend Walker

Townsend Walker draws inspiration from cemeteries, foreign places, violence and strong women. A collection of short stories, "3 Women, 4 Towns, 5 Bodies & other stories," 2018. Winner of a Book Excellence Award, an Eyelands Award, and a Silver Feathered Quill Award. A novella, "La Ronde," 2015. Over 100 short stories and poems have been published in literary journals and included in 15 anthologies. Short Story Awards: two nominations for the PEN/O.Henry Award, first place in the SLO NightWriters contest. Four stories were performed at the New Short Fiction Series in Hollywood. He reviews for the "New York Journal of Books." During a career in banking, he wrote three books on finance: "A Guide for Using the Foreign Exchange Market," "Managing Risk with Derivatives," and "Managing Lease Portfolios."