You have no items in your cart. Want to get some nice things?

Go shopping

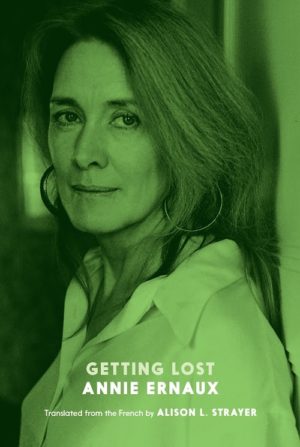

In this personal account of hopes unfulfilled, Annie Ernaux leaves one with a desolate sense of what the author herself terms as “failure at living.” It is difficult for the reader to recover from this discomfort, having understood Ernaux’s life of suffering entangled in lust, love, and loss.

Throughout this naked telling, Ernaux reveals a past littered with thorny experiences in love and heartache, on which several of her earlier novels are based. Translated from the French by Alison L. Strayer, Getting Lost is a bald expression of the author’s destructive obsession during her secret love affair with a younger, married man. In this diary, she confesses to committing the same errors in past relationships, continually complicating them with anxious suspicions and imaginary constructions of breakup. It becomes clear that Ernaux has a tortured history of spinning herself up into an emotional state of ruin. We see the picture, painted bit by bit, of the author’s “inner lack,” having lived a life immersed in the need for men who do not love her. Or perhaps they do, or did, were it not for her habit of “thinking first of catastrophe,” driving herself and her companion into despair with her visions of unhappiness.

A well-known French writer, Ernaux has been a keeper of diaries and journals since the age of sixteen. Getting Lost describes only one in a string of love-life disappointments. It is written when the author enters a passionate love affair at the age of forty-eight with a thirty-five-year-old Russian diplomat posted in Paris. Her sizzling accounts of their sexual interactions leave little to the imagination, and the reader swings with Ernaux between elation and dejection. She is drawn to her Soviet lover just as she is drawn to “Russia, a near-imaginary country,” during a period in history immediately before the fall of the Berlin Wall. She moves in circles of social distinction, attending dinners and events with ambassadors, presidents, and monarchs. In this record, though, there is little of the outside world reflected, as Ernaux immerses herself in writing chiefly of her deep desire, her jealousies, her self-recrimination, and the depths of her “blank, speechless pain.”

Ernaux finds herself so captivated that she is unable to write professionally, and unable to manage with any enthusiasm the other obligations in life. Instead, she waits in agony for his next call, their next sexual engagement. These intense encounters bring her physical joy, yet her tragic focus during the year-long assignation teeters between her advancing age, and her seemingly hopeless perception of self, stating, “… how am I to believe that people can love me, become attached to me?”

The vulnerable account Ernaux relates in Getting Lost suggests the devastating cycle of black-and-white thinking. This cognitive distortion leaves her deprived of sound middle ground from which to participate in an exciting interval of her life. Thinking dichotomously, she is unable to make sound judgments, continually deciding she must break things off – he is married, after all, and is only in France temporarily; he will return to Moscow – yet she finds the next excuse to see him one more time, to experience those heights of passion. She mourns her habit of showering him with gifts, understanding that “… this does nothing to bind him [to me], but makes him proud (of arousing so much love) and heightens his narcissism…” Yet all the while, she realizes that this works against her, the giver. “Well anyway, I love him with all my emptiness.” In her own words, she tells us that she lives in a state of subjugation, “driven by an old urge for destruction.”

Ernaux reveals an understanding of her dilemma, relating that sex has always been a source of anxiety in her life. She drags the reader with her from the heights of “beauty, passion, desire” down to her unvarnished assessment of her lover. She describes him as a conformist, quite lacking in character, his intellect unremarkable, his behavior like that of a gigolo, while he drinks her Chivas and takes her cigarette packets. But she is compelled to disregard his flaws in order to present her “perfect passion.” She tells us, “I make love with the same desire for perfection that I feel in relation to writing.”

I believe that reading Ernaux’s earlier works could provide context to the exhausting experience of Getting Lost – the factors of family and society that may have steered the author’s life into this addiction to losing love. In A Girl’s Story, Ernaux describes her life as an eighteen-year-old, submitting her will to a man’s, who then moves on, leaving her bereft, without a “master.” A Woman’s Story, A Man’s Place, and Simple Passion were recognized as The New York Times Notable Books. Shame was named a Publishers Weekly Best Book of 1998, I Remain in Darkness a Top Memoir of 1999 by The Washington Post, and The Possession was listed as a Top Ten Book of 2008 by More Magazine. Her historical memoir, The Years, provides a look at her life in French society just after WWII until the early 2000s.

Getting Lost shares an astonishing confession, as Ernaux equates writing with suffering, a “conjunction of loss and the book to write.” In her syncretism of writing with torment and failure, Ernaux suggests that her lover is only attracted to her for her glory, her fame as a writer – “all those things that are built on my suffering,” she says – and in the case of this affair, “the very forces at play in our relationship.”

She defines her inner anguish as equal to her obligation to write, saying “… I understand that desire, writing and death have always been interchangeable to me.” A first, I was shocked by this statement – interchangeable? Yet, I have come away with a sense that Ernaux’s bare words describe the essence of relentless internal struggle in which memoirists must engage to tell a difficult story.

The haunted feeling that Getting Lost evokes in the reader is difficult to shake. One is left submerged in Ernaux’s world, gasping for breath, and fighting for reason. And the question she asks herself, “Which is truer, desire or guilt?” has remained with me, unanswered, ever since I closed this book upon its last page.

by Annie Ernaux

Translated from the French by Alison L. Strayer

Seven Stories Press, 192 pages

Ingrid Petty

Ingrid Petty is an author of narrative non-fiction and aspiring memoirist based in San Antonio, Texas. After a career in law and philanthropy, she wrote her first book, "The Kronkosky Foundation Story: Creating Profound Good through Community Philanthropy," published by Trinity University Press and Maverick Books in November 2021.

- Web |

- More Posts(1)