You have no items in your cart. Want to get some nice things?

Go shopping

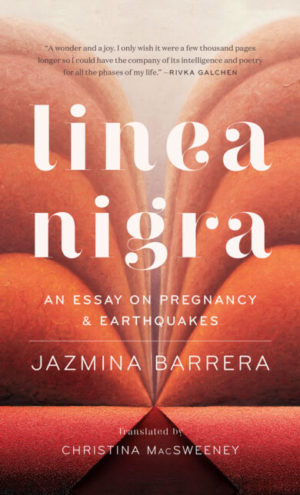

While many would expect birth narratives to be cleaved into a neat before and after, Jazmina Barrera’s Linea Nigra is a playful collection of imagistic snapshots that uses several ways of seeing, to relay the transformative experience of the pregnant writer. Through a varied and interwoven stream of consciousness, this four-part work includes dreams; meditations on and intertextuality between other artists’ work and lives; earthquakes, (which Mexico is prone to) and their metaphorical weight; and, most significantly, the art of writing.

While her treatment of time is linear in the loosest sense, Barrera’s narrative self is un-moored by pregnancy.This fragmented self is not necessarily a troubled one, rather one that is malleable in its transformation. As Barrera writes, “Even when I’m decidedly sad or angry, a part of me is deliciously, ridiculously happy. There are moments like that, when I’m completely split in two.” This splitting or separation from the self is an ongoing process exemplified in the symbolic-as when the narrator views a solar eclipse through a puddle of water, or reflects on the titular “linea nigra” (a dark vertical line that emerges across the abdomen in pregnancy)- and in more mundane moments, through the realisation of her continually shifting priorities as her body changes.

For Barrera, unification of selves is not the aim, even if it were possible, but understanding and documenting it is. To help excavate meaning across this period, she turns to her native country and its past. These explorations are grounded in tender mythology from Mexico’s indigenous populations, from Aztec art, and contemporary figures in Mexico City’s vibrant history. These include Tina Modotti and Frida Kahlo – both of whom were unable to have children due to their chronic illnesses. The latter two figures were close friends and contemporaries who expressed their desire for pregnancy and experience of loss using symbolism across their wide bodies of work. Barrera, too, uses her craft to ascertain meaning, parsing symbols from a variety of pregnancy resources such as paintings, guidebooks, advice from friends and her matrilineal family.

Tracing these bodily changes and thoughts throughout her pregnancy, Barrera initially agrees with her friend who jokingly suggests the first trimester is like a hangover. The nausea, lack of energy, and how sensorily overwhelming certain situations can rapidly become, speaks to many experiences including and outside of pregnancy, such as chronic illness and disability. This exhaustion Barrera experiences is bone-deep and something that will resonate with many unwell people: “I try to set myself one task each day. Just one: cut my nails or send an email. But I don’t manage it. There’s no time.”

I am at the age at which many of my friends are starting to have children, if they do not have them already. A larger portion of my friends are chronically ill and have already made the decision to remain child free, the burdens of their own bodies too great to support another. I, too, fall into this latter category, childbirth having been previously offered as a temporary ‘cure’ for endometriosis – a false solution offered by several male gynaecologists.

In Linea Nigra, medicine’s silently overarching hand takes the form of Barerra’s gynaecologist, who comes recommended by another pregnant friend and posts inspirational quotes on his Twitter page. Yet his reputation is marred by administrative disagreements and hospital changes, inconveniencing existing patients, and a rumour that a woman lost her baby in childbirth due to his oversight. Now heavily pregnant, Barerra is horrified. Her partner Alejandro is Chilean and relays Violetta Parra’s “Rin de Angelito”, which honours dead children, a lyrical space to hold that thin liminality between life and death. On Parra’s loss of her own child at nine months old she writes, “I almost didn’t write this fragment from pure grief,” and elsewhere she ushers out similar thoughts as if speaking of the terrible will bring it into being. But here and throughout the book, Barerra allows space for death and grief, the former of which is “like a playmate” to Mexican children, due to popular nursery songs and the widespread celebration of the Día de Muertos. In such moments, she gently reforms her own relationship with potential loss. Life and death are bedfellows, and her grief of bodily limitations strikes a chord particularly later on in the narrative, when her mother, now a grandmother, is diagnosed with ovarian cancer.

One of the most important transformations in Linea Nigra is Barerra’s relationship to her craft. In the third section, “white nights,” she oscillates between mother and writer. An expert at multitasking, she reads slim volumes she can hold in one hand as Silvestre is feeding, and writes notes on her phone while he sleeps. These snatches of productivity -and with them the difficulty in concentrating once the desired alone time finally arrives-are particularly relatable. This form can be seen across many female writers and artists cited by Barrera whom I also admire. The Venezuelan painter Luchita Hurtado springs to mind, whose headless self-portraits were produced in a small closet while her children slept. Sinead Gleeson, the Irish author of Constellations, also revels in the fragmentary, writing the essays that make up her collection between illness and childbirth. Sylvia Plath famously documented childbirth in her journals and poetry, with motherhood becoming a major theme in her late work. That Barerra doesn’t erase these moments of interrupted time places equal emphasis on their importance, positioning her own journey of motherhood and work amongst a considerable canon of female creatives.

The act of writing in Linea Nigra is characterised by moments between obligations. Throughout, Barerra chastises herself for struggling to focus on a grant-funded project, finding her baby diary an easier, albeit “hackneyed” alternative. In documenting her own experiences, she “looks for texts on pregnancy as if they were travel guides,” though literary sources are few and far between. She is exasperated when, translating a series of essays with her husband, she discovers another author has recollected the same anecdote of Mary Wolstonecraft dying while birthing her daughter, Mary Shelley: “It’s impossible to be original when you write about being a mother. There are so many of us and our experiences have so much in common; despite any differences, we have so very much in common.” It is this seeking of commonality that make Barerra’s streams of consciousness inviting to the reader, regardless of whether they are pregnant, parents, either, or neither. The expansive range of subjects introduced in Linea Nigra make it not only a book about the selves that we become and must say goodbye to, but also about the craft of writing and reforming what a book can be. Motherhood and its attendant physical change is a collective experience and however it is recorded it should be considered, as Barerra suggests, part of several “new literary genres.”The diaristic fragments work for Barerra in a material sense – “ I write this fragment based on the notes I’ve made on my phone. I know I have only a little time so I stick to the point,” – but also for a reader who may be in a similarly energy-limiting situation. This book is part of a “new mode of writing” for her, but also an invitation to readers to re-evaluate and rupture the literary canon: “In my opinion, there will never be enough of us. I think of newspapers, lists, letters, herbals, textbooks, pregnancy journals and diaries, homemade cookbooks: all these forms of writing are, or can be, literature.”

Barrera quotes Virginia Woolf, who also wrote on the fallibility of language to express illness, reminding us that: “Writing the body, as Woolf urged, is only the beginning. We have to rewrite the world.” Like her contemporary Valeria Luiselli, the author works wonders with the fragmentary, but never lacks depth or breadth. Linea Nigra is a journey into an elsewhere, a documentation of self-transformation, and a rewriting of the world of the body that I will return to again and again.

Linea Nigra: An Essay on Pregnancy and Earthquakes

By Jazmina Barrera

Translated from the Spanish by Christina MacSweeney

Two Lines Press, 160 pages

Jennifer Brough

Jennifer Brough (she/they) is a slow writer and workshop facilitator based in Nottingham. She is working on her first poetry pamphlet, Occult Pain, which explores the body, pain, and gender through a magical, disability justice lens. She is also the founding member of resting up collective, an interdisciplinary sick group of artists that offers workshops on rest and creativity. Find her on Instagram @occultpain

- Web |

- More Posts(6)