You have no items in your cart. Want to get some nice things?

Go shopping

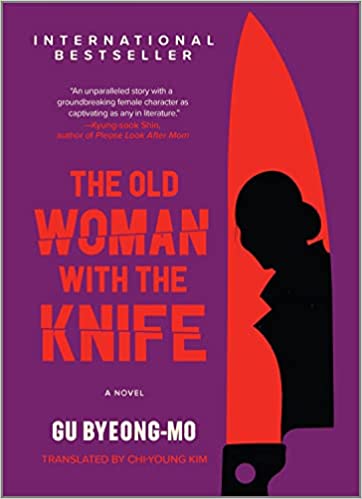

“She is actually sixty-five years old, but the number and depth of the grooves in her face make her look closer to eighty. The way she carries herself and the way she dresses won’t leave a strong impression on anyone.” Nearing the end of her career, “disease control specialist” Hornclaw feels the aching weight of all her experiences and losses. In a body that isn’t as strong as it used to be, she works to carry out her remaining kill contracts, and hopes that her name won’t end up on a target list one day. But most of all, she carries a hope of finding meaning beyond the work she’s done for most of her life. When a job goes wrong, it sends her straight into the lives of a young doctor and his family, awakening desires long dormant inside her. And at her age, it doesn’t feel worth it to ignore them anymore, even if it means making herself vulnerable to certain ghosts from her past. In The Old Woman with The Knife, Gu Byeong-Mo, the award-winning Korean novelist, has given us more than a thrilling tale of a 65-year-old female contract killer – it’s also a thoughtful illustration of aging and self-acceptance. Her work has been translated into Spanish and French, and the English-speaking world has at last gained access into the mind of this deeply thoughtful storyteller.

Nothing in Hornclaw’s life feels very permanent or involved. She doesn’t have friends or family. Her refrigerator is mostly empty and if she does buy food, she forgets it’s there until it spoils. We understand that as a for-hire killer, she can’t afford involvements, which is what makes the relationship she has with her dog, Deadweight, so poignant. Hornclaw forgets to feed her, forgets to leave her water, but never for very long. And much to Deadweight’s credit, she never seems to hold a grudge against her owner. Before Hornclaw leaves for a job, she cuddles and talks to her, almost ritualistically. “So when the time comes, get out of here and go where you need to go. Before you’re considered worthless even though you’re still alive.” Hornclaw says this to Deadweight, as though the dog can understand her verbal instructions to leave their home, should she fail to return from a job alive. There’s a feeling, however, that Hornclaw sees herself in Deadweight. It’s like a prayer, something the reader can imagine she’s told herself, every time she feels dismissed as old, frail, and insignificant. And even though she tries to prepare the dog for the very real possibility that she won’t return, she still says “I’ll be back” each time she leaves. She is reassuring herself as much as she is the dog, and that’s a tender and vulnerable thing for a contract killer to do. The reader learns later that it was with similar tenderness that she was first, as a young girl, indoctrinated into the world of for-hire killing.

Hornclaw is endearing in a way that’s unusual for the “bad guy” in the thriller genre. At the start of the book, the reader might expect to enjoy disliking Hornclaw, and is certainly hoping to love to hate her. Having been a killer-for-hire for her entire career, she must not only be good at it, but like it as well – so our chances of developing any moral or human connection with the villain are slim. But that’s not why we read thrillers. As the name suggests, thrillers are meant to delight, to fascinate, and to mystify. They offer us a glimpse into the world of people we couldn’t imagine meeting, much less being, so that when we close the book, we’re even more thankful for the safe and predictable world we live in. The great villains of literature have been the ones we love to hate – the intelligence and cunning of Professor Moriarty and Hannibal Lector kept us turning the pages to see what wild tales were to come. In The Old Woman with The Knife, Hornclaw is also cunning, and highly intelligent. Everything she does is premeditated with the care and hyper-awareness of an expert assassin. She occasionally kills just because she feels it’s appropriate, exaggerating her appearance as a frugal old woman to hide her power and aggression. “Clipping one’s nails short and leaving them bare is one of the hundreds of passive ways to conceal one’s strength.” The kill scenes are charged with energy and range from poetic, “…his frozen, open pupils in his bluish face are like tunnels filled with deep, compacted darkness containing the end of the world,” to medically vivid: “…by the time she gets to her feet, he’s managed to pull the knife out of his thigh, severing his leg’s lateral muscle.” But unlike Moriarty and Lector, Hornclaw isn’t a nemesis. She’s the title character (which, in fact, makes her the heroine) and she ultimately offers us a different perspective: She may be a trained killer, but she’s also flesh and blood, a woman trying to reconcile her own sense of self with the way society views her. And that’s highly relatable. It’s something we all face at some point in our own lives. Hornclaw becomes more than an expert assassin. She becomes an old woman with a knife, causing us to ask: in a life spent poised for a fight, has she ever had pause to wonder just who that fight is for? Have any of us?

The story is told in the 3rd person, mostly from the perspective of Hornclaw. A noticeable quality in Byeong-Mo’s style is the unique way she paints a scene using the character’s inner world and private experience. A short conversation or interaction can go on for pages – without the pace suffering – because between each spoken line, Gu illustrates sub-processes which are at once so relatable, and so paranoid, like a skilled assassin would be. In a scene between Hornclaw and Bullfight, a fellow agent with a grudge, it is Hornclaw’s own thoughts which drive the tension more than anything else which is verbalized. “What the hell? Her heart stops, but her expression doesn’t change. Then again, she might believe she’s maintaining a calm, unruffled exterior, but he could have caught the corner of her upturned mouth or one eye trembling ever so slightly. She suppresses the urge to blurt, How do you know that – which would amount to digging her own grave – and actually it would be better to retort, What is this nonsense, what evidence do you have, and grab him by the throat – as she fingers the Buck knife in the inner pocket of her jacket.” These thoughts not only drive the tension in the scene (and between the characters, leading to a gripping climax) they show the reader something about Hornclaw, something that comes back throughout the book: Hornclaw makes her choices with precision and care, and her next move is always hidden from view, surprising both the characters in the book, and the reader.

There is only one element in the book that doesn’t quite land, and that’s the rivalry between Hornclaw and Bullfight. As explained, Bullfight (who is about half the age of Hornclaw) had a traumatic experience with her many years before when he was a boy. For Hornclaw, this incident has vanished from recall and faded into the blur of her life. If the reader expects (as they couldn’t be blamed for doing) that he became a disease control specialist in order to exact his revenge, the explanation given is rather unsatisfying: “He didn’t have a desperate, otherworldly desire to do this work, driven to resolve his baggage with other baggage. It wasn’t that he especially loved getting rid of people, but as he didn’t have a strong sense of morality…he somehow – truly, just somehow – ended up doing this work. Most of what happened was a collage, created by the shapes and layers of unimportant events. His life was a totality of somehows.” Beautiful as the writing is, the portrayal of Bullfight as an assassin without a moral compass doesn’t help the reader understand the rage he feels toward Hornclaw. The climactic scene between the two of them is carried well by the cinematic storytelling, but all the while I couldn’t help but wonder: What happened to the palpability of emotion? Gu provides us with intimate narration for Hornclaw, but it doesn’t extend to Bullfight enough to help the reader believe their rivalry. Throughout the book, he seems to enjoy aggravating her and making her feel insecure and watched. It seems more sadistic than angry, and revenge isn’t carried by sadism. But if he’s meant to just be evil, why would he be hunting for revenge? I didn’t feel his anger as I needed to feel it.

While there are shifts at times between characters, the story is told primarily from an intimate 3rd person point of view. Gu makes full use of that intimacy by underscoring Hornclaw’s experience with language that calls up the senses of the reader. Chi-Young Kim, the Korean English translator responsible for helping The Old Woman with The Knife reach the English-speaking world, has splendidly captured the poetry in Gu’s narrative style. A word someone says to her melts “like ice cream along the outer edge of her ear.” Blundering her words towards a man for whom she has tender feelings, “she wishes the words had a texture and a shape so that she could crumble them like cookies as they emerge from her mouth.” When Hornclaw eats a tangerine, “…her tongue wraps around it, and a sweet coolness fills her mouth, elevating her serotonin levels.” These feel too close to be something the character of Hornclaw would, or even be able to, describe herself. It’s these deeply felt reactions and physiological sensations which give the reader a kind of body-feel voyeurism. Gu is guiding us to think and feel things that Hornclaw herself isn’t even aware she’s thinking and feeling. The reader gets the chance to become her.

Through the character of Hornclaw, Gu weaves together the gripping and sometimes heartbreaking tales of a contract killer trying to outrun her past, and the poignant experiences of a woman reestablishing her view of herself at an older age. Hornclaw forces the reader to consider the high value that society places on youth. Isn’t it true that as we grow older, we become enriched by our experiences? That our skills become honed over time, our knowledge becoming deeper from the wisdom that only age can bring? And shouldn’t our desires by extension become deeper, less clouded by the confusion of youth? Packaged as a thriller, The Old Woman with The Knife tells the story of a woman that we all surely know, leading the reader through a sensational plot to an ending that cannot fail to leave a lasting impression.

by Gu Byeong-Mo

Translated from the Korean by Chi-Young Kim

Harper Collins, 288 pages

Eleanor Keisman

Eleanor is an American writer and graduate student. Originally from New York and Hawaii, she spent 10 years working in Czechia, Poland, and China as an EFL teacher before settling in Austria. She holds a Bachelor’s of Liberal Arts from The New School, studied French at the Alliance Française, and speaks fluent German. Her short stories and essays have appeared on 21-magazine.org and the Sunday Writer's Club blog. She publishes weekly flash fiction on Instagram. When she's not reading, writing, or studying, she cooks, hikes, and tries to make friends with stray cats.