You have no items in your cart. Want to get some nice things?

Go shopping

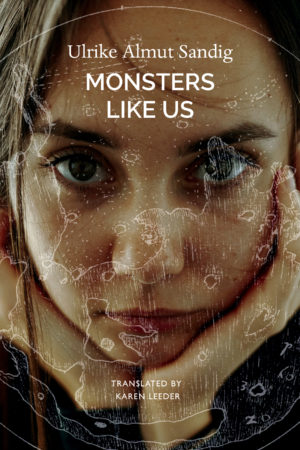

Monsters Like Us is a novel that confounded my expectations. The fact that author Ulrike Almut Sandig grew up in former East Germany, together with the cover of the German edition – showing a faceless boy and girl hand-in-hand in front of an anonymous block of flats – led me to expect a gritty teenage love story against the background of decaying late communism. Or perhaps a coming-of-age novel set against the turbulent transition from a one-party state to German reunification. But the focus of Sandig’s narrative lies elsewhere. The setting of the first half of the novel is very specifically East German – but the main themes are psychological rather than political.

In a child’s mind, imaginary beings can be as substantial as the next-door neighbours or primary school teachers. For the very young, the dividing line between the imaginary and the real is permeable. Fauns and lions with the gift of speech dwell just beyond the child’s wardrobe door, while the nocturnal screech of an owl can conjure up fears of goblins and orcs. Supernatural beings lurk everywhere in the child’s world. So it is not surprising at first sight that Ruth, the first-person narrator of the first and last sections of the novel, has an abiding fear of vampires throughout her childhood.

What is more unusual is that she believes her grandfather to be one. She wonders why her mother identifies the marks on her neck as horsefly bites rather than the imprint of vampire fangs. Ruth’s repeated references to how her grandfather sucks her blood reveal that she is a victim of long-term sexual abuse, and there are suggestions that he may also have abused her mother. While Sandig refrains from describing this abuse in realistic terms, the vampire imagery is almost worse. The very fact that Ruth cannot say exactly what happened to her conveys the depth of her trauma. She compartmentalises herself and engages in mental disassociation, becoming alienated from her own body. Her brother Fly’s nickname for her, “Dummy-doll,” reflects the way she experiences abuse by her grandfather; she feels like a powerless plaything.

Monsters Like Us explores the violence human beings inflict on one another both within families and in other settings, with a particular emphasis on sexual abuse. It falls into three sections of different lengths, centring respectively on Ruth and her childhood friend Viktor, with the last section, in Ruth’s voice, being addressed to her boyfriend Voitto.

Although Ruth and her brother Fly grow up in a vicarage, their childhood is marred by repeated conflicts between their parents, culminating in a temporary separation. Violence – both physical and psychological – is a regular occurrence. Their parents bicker, their father constantly puts their mother down, and she accuses him, with some justification, of cowardice. He methodically chastises his own children and raps pupils in confirmation classes on the side of the head with his knuckles. The neighbours fight among themselves, while the Soviet soldiers stationed in their small town are bullied by their commanders. At another level, political oppression is ever-present. Ruth and Fly’s father became a pastor not necessarily out of a deep vocation, but because he was debarred from other forms of higher education for refusing to take military training and questioning the accuracy of the Party newspaper.

Viktor, the son of a non-commissioned officer in the East German army and his second wife, (from Ukraine), comes in for teasing and bullying as an outsider – ironically enough, people call him ‘the little Russian’ – and sexual exploitation. He is unable to tell his parents that his half-sister’s boyfriend rapes him every time he gets the opportunity. Like Ruth, Viktor cannot find the words to describe what is happening to him. Both children believe that ‘if you don’t talk about it, then it hasn’t really happened.’ While Ruth seeks solace in learning to play the organ and the violin, Viktor finds neo-Nazi pals who help him toughen up. What begins as a self-defensive mechanism spills over into extreme, anti-social physical violence. When, after the fall of communism, Viktor finds himself an au-pair position in the south of France, it looks as if his life might take a different turning. Yet it is not so easy to escape from violence and abuse, which prove to be inescapable even in the most idyllic of settings.

Ruth and Viktor, linked by early experiences of sexual violence, deal with it in very different ways that are arguably gender-typical. The sections of the book that centre on Ruth, written in the first person, are addressed to her abusive Finnish boyfriend. While on the surface she has triumphed over her difficult early life, becoming a concert pianist in demand throughout Europe and beyond, she still lacks sufficient self-esteem to withstand Voitto’s criticisms and physical bullying. Viktor, by contrast, channels his pent-up pain into outbursts of rage which are ultimately self-destructive.

Despite the trauma that lies at the heart of this novel, it also contains evocative vignettes of ‘never-ending childhood.’ These range from the commonplace – such as swimming in the local flooded quarry and feeding fermenting red currants to next door’s chickens until they fall over in a drunken stupor – to the extreme: in one scene, Fly and Ruth’s experiment with setting fire to glue culminates in a dangerous blaze in their shared bedroom and the intervention of a Soviet soldier to save the two children.

Ulrike Almut Sandig is best known as a poet and Klangkünstlerin (sound artist). Her debut novel also derives much of its evocative power from the skillful use of onomatopoeia, assonance, alliteration and other devices. These are well conveyed in Karen Leeder’s sensitive translation. To take just one instance, the opening page of Ruth’s first section describes the imagined experience of lying in her mother’s womb listening to all the sounds from outside:

‘Von außerhalb der Bauchdecke hörte ich Geräusche, ein Öffnen und Schließen von Türen oder Eisenluken, ein Schaufeln und Schaben von Eisen auf Eisen, gedämpftes Knistern und Knacken, rhythmisches Donnern wie von Kohlen beim Aufprall und das Kratzen der Ofenzange, unterbrochen von ihrer Stimme, die jemandem etwas mitzuteilen schien.’

Leeder renders this passage as: “From the other side of the abdominal wall, I heard noises, doors opening and closing, an iron hatch, a shovel and the scraping of iron on iron, muted creaking and crackling, a rhythmic thunder like the clatter of coal, and the scratching of oven tongs, interrupted by her voice, that seemed to be telling someone something.” This successfully maintains both the overall rhythm of the original sentence and its use of onomatopoeic alliteration (e.g. “Knistern und Knacken,” translated as “creaking and crackling”). Where it is impossible to retain alliteration (‘Kohlen (…) und Kratzen’ becomes ‘coal (…) and tongs’), Leeder cleverly adds another k sound, “the clatter of coal.”

This musicality, together with the compelling narrative, makes Monsters Like Us a novel to be read and re-read; one discovers different layers of meaning on revisiting the text. Though pervaded by melancholy, it offers some hope for a better future, at least in the figure of Ruth. Far from being the “dummy-doll” of her childhood, she ultimately finds the strength to rebel and stand up for herself.

Monsters Like Us

by Ulrike Almut Sandig,

Translated from the German by Karen Leeder

Seagull Books, 230 pages

Fiona Graham

Fiona Graham is a literary translator and reviewer. Since taking a BA Honours in German and French (Oxford) and an MA in linguistics (Reading), she has worked as a translator and editor at the Dutch Foreign Office and in the European Union institutions. Fiona was Reviews Editor at the 'Swedish Book Review' from 2014 to spring 2022, and also reviews for the European Literature Network. Her translations include Elisabeth Åsbrink’s English Pen Award-winning '1947: When Now Begins'.

- Web |

- More Posts(1)