You have no items in your cart. Want to get some nice things?

Go shopping

Tiffany Tsao is a writer and literary translator. Of Chinese-Indonesian descent, she was born in the US but spent much of her childhood and adolescence in Singapore and Indonesia. Her translations from Indonesian to English include Norman Erikson Pasaribu’s poetry collection Sergius Seeks Bacchus, Dee Lestari’s novel Paper Boats, and Laksmi Pamuntjak’s The Birdwoman’s Palate. She currently lives with her family in Australia.

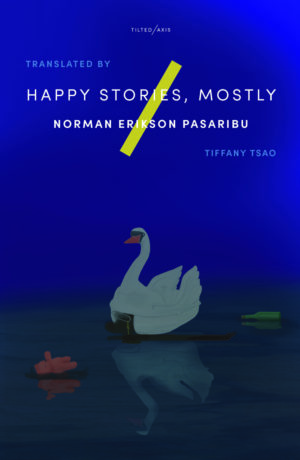

Her latest work is a translation of Norman Erikson Pasaribu’s short story collection Happy Stories, Mostly which examines the “almost” happiness that so often defines queer experience. Often comic and deeply dark, these stories portray the sense of loss that for many accompanies ethnic, religious, or sexual alterity. The translation of Happy Stories, Mostly is published by Tilted Axis Press.

Jane Downs: To begin, I was wondering if you could tell me a little more about the languages spoken in Indonesia today, and in particular the language that you translated Happy Stories, Mostly from?

Tiffany Tsao: Indonesian is quite an interesting language, because it started out as a state-imposed language as there was so much linguistic, ethnic, and cultural diversity. It was the lingua franca of the archipelago during the colonial era. It’s very similar to modern-day Malay. It’s called Bahasa Indonesia which just means Indonesian language. Before its imposition, most people spoke different languages like Javanese (the Javanese are the ethnic majority of Indonesia), Balinese, and Bataknese – which is Norman’s heritage language – but the official language played a considerable role in the anti-colonial struggle and in state building. For a very long time it wasn’t a mother tongue for the people who were speaking it, so even into the 1980s you could see people still not being that comfortable with Indonesian as it was sort of their second language.

JD: So people had a language that they spoke at school and then another that they used at home and in the community?

TT: Yes, but that sort of changed as time went on. As late as the 1980s, writers would more naturally write in their home language, but Indonesian was seen as the modern language because it was the language of the nation and so now, today, you have really got to the stage where people speak it at home, quite normally.

JD: Do the other languages manage to survive?

TT: Yes, they do. People often still have their other secondary language, and it depends on the situation whether they are as fluent in it as in Indonesian. So, for example, for Norman he knows some Bataknese but he’s more fluent in Indonesian. In my case, my parents speak Indonesian quite well, but my grandmother grew up on an island called Bangka and even though she knows Indonesian, she will naturally slip into her Bangkanese dialect.

JD: So, Norman is working and writing in Indonesian. Does it have a long literary tradition as a language? Is the novel or the short story a traditional form of storytelling, or has it been imported from Europe and Western literature?

TT: Traditionally literature would not have been the novel or the short story. Traditionally it would have been more oral – poems or long epics – because just like in Europe, few people were literate. Around the turn of the century, in the 1920s and 30s, you start to see things like newspapers emerging, with people very quickly adopting European forms because of colonisation, so short stories started appearing but what is different from in the West is that the short story and poetry are still quite popular forms. All of the major papers have a poetry section and a short story section or publish short story serials – it’s quite a common thing.

JD: So Norman’s work fits quite well into that tradition?

TT: Yes, but ironically because Norman is queer it’s not so straightforward. Although he did have a few of his short stories published, they were not obviously queer ones, so those have never been published. The (newspaper) rubrics are standard and so it’s tricky to fit Norman in because he’s queer, he’s from an ethic minority, and because Christianity features a lot in his stories. Indonesia is a predominantly Muslim country, so a lot depends on what editors feel comfortable publishing.

JD: Do you think, then, that in Indonesia there a certain amount of self-censorship on the part of publishers when it comes to queer content?

TT: I think so. I know that his publisher – who is the largest publisher in Indonesia – did change a few things in his poetry collection, things that Norman changed back or reworked for his English edition. We work quite closely together, and his English is excellent, so we go back and forth on my translations of his work, and I know that there were some things that he wanted to put back in because they’d originally been taken out. The editor felt that it was better to be more cautious.

JD: I’d love to know more about your working relationship with Norman. How do you access his imaginary space?

TT: We got to know each other through social media. He posted some of his poems that he’d self-translated, and I thought they looked really interesting. At the time I was working as the country editor for Asymptote Magazine, and I said, “You know, I think your work is really cool, I’d love to work with you on a translation.” He agreed, but I was hesitant because I don’t think I’m that great with poetry as I’m a novelist, but he said, “No, I think it’s great, I have a good feeling,” and I was very touched. As a result I wanted to correspond quite closely with him and he wanted to be very hands on, which is not always a good combo, so there was a time when we were having trouble syncing and at first it was sort of like a tug of war, but then we began figuring out each other’s style and understanding how each other’s brain worked and I don’t think I have ever gotten as close to a writer before as [I have to] Norman. We began corresponding a lot and we became very close friends, so we weren’t tugging of war anymore and it became more fun, and we were sort of like swimming along together.

JD: One of the things I like about Norman’s stories is that they are very bittersweet. For those who haven’t read them, how you would describe them?

TT: This particular collection is really difficult to describe, but it’s called Happy Stories, Mostly, which in Indonesian could be translated in two ways: either as happy stories, mostly or happy stories, almost all. That almost is key as in Indonesian almost is hampir, which is very close to vampir or vampire. For Norman, that almost is what unites the collection: It’s about queer lives and queer stories, about being almost happy. And that’s what’s true for a lot of the stories, there is this almost happiness – this sense of being nearly happy, very nearly happy, or even actually happy, and then having it snatched away. But it’s not enough just to be almost happy and, as Norman says at the beginning of the book, “queer folk” are always getting thrown to the hampir – or the vampire that sucks the life out of them and steals their joy.

JD: The stories also strike me as being very urban, very young and rooted in contemporary culture. There’s a lot of Indonesia in there, but at the same time a lot that transcends national borders. The stories seem to address what it is to be a 30-something in a contemporary world in which identity is a very big piece of the conversation.

TT: Yes. There is one story, “The True Story of the Story of the Giant,” which is really interesting, because it tells of that sort of contemporary searching for roots, of wanting to go back to some sort of precolonial era where a giant man might have been able to exist. I think in that story there’s a sense of longing. At one point the narrator says that he doesn’t have a role model, and there’s a sense of culture being lost, because he has had to move away from his family and is estranged from his father, who is Batak. There’s this sense of being unmoored, of not having a strong cultural past because he is from an ethnic minority. So, when narrator goes looking for the giant, he’s also looking for the story of his own past and yet he ends up in a museum where he’s told he’ll not find the thing he is looking for, and there’s nothing left for him.

JD: These issues of identity extend perhaps into translation, too. I’m thinking about the Amanda Gorman controversy that flared up after Biden’s inauguration, when the #own voices movement advocated “that stories about marginalised people be written by authors who share the same identity and experience,” protesting against the choice of a white male to translate her work into Spanish. Do you think it’s necessary for the experience of a person to be only communicated by somebody who shares that experience? To what extent do you feel that it’s necessary to share the life experience of an author, to do justice to their work?

TT: I would say that if I weren’t working so closely with Norman, I would be worried about my ability to translate him. Norman has shared much with me in terms of everyday feelings, which I think has been critical to how I translate him. Without it, you know, I do think I would be in danger of changing the work because I’m not queer and Norman is. You know, Norman is translating my own novel Majesties into Indonesian and it’s about the Chinese-Indonesian experience and it takes place against the backdrop of anti-Chinese discrimination as well. I think that because Norman is also from an ethnic minority, he is more familiar with the situation, whereas if my novel were being translated by someone from the majority – by let’s say a Javanese, Muslim male – it might not turn out the same way.

JD: Before we end, I would love to know what sort of books you particularly enjoy and if there is anyone in particular that you would really like to translate?

TT: I am a bit eclectic in my tastes and just sort of read things as I happen upon them. I’ve been drawn more recently to weird and speculative fiction and I’m reading Cursed Bunny. It’s a Korean short story collection by Bora Chung, translated by Anton Hur, and I really am enjoying it very much, although I’m also completely weirded out by it! I also really liked Arid Dreams by Duanwad Pimwana, translated by Mui Poopoksakul. It’s this amazing Thai short story collection where you often start off thinking the stories are about men, but it turns out that it’s the women who are at the stories’ hearts. And also Imminence by Mariana Dimópulos, translated by Alice Whitmore. I really liked that. It’s very much in the woman’s head, and she’s not going through a very good time and so it moves back and forth between the past and present. I tend to like things that have a sort of psychological element to them, and when the language reflects that.

In terms of Indonesian authors l would like to translate, I was very lucky recently as I got to translate one of my dream authors. The book’s coming out in April next year with Penguin Classics, and the title is People From Bloomington by Budi Darma. I feel he’s most famous for his stories, but he was also an essayist and a well-respected critic, and he’s also written really interesting novels, but what I really liked about this collection is that it is set in Bloomington, Indiana, and actually isn’t really about Indonesians but Americans. It was a challenge to translate and get published because, you know, Indonesian literature just hasn’t reached the same saturation level as [that of] Japan and now South Korea. It’s still at the stage where people are like: “I want to learn about Indonesia and that’s why I want to read this book.” So, it was a huge triumph when our agent was able to land Penguin Classics – I let out this large roar of triumph!

JD: Perhaps it’s just a question of time? Of people getting more familiar with the idea of reading Indonesian literature? Maybe this collection of short stories is going to be one step on the way!

TT: To me it seems more correlated with economics. South Korea’s economically doing quite well, and I know that the government has been putting a lot of funding into promotion and Indonesia just isn’t in that space; but, yes, let’s hope that that book and Norman’s collection will be two more stepping-stones towards gaining Indonesian literature even more visibility.

Jane Downs

Having grown up in the south of England, Jane went on to study Arabic at university, travelling extensively in the Middle East and North Africa before putting down roots in Paris. Her work includes short stories, poetry, reportage and radio drama. Her audio drama "Battle Cries" was produced by the Wireless Theatre Company in 2013. Her short stories and articles have been published by Pen and Brush and Minerva Rising in the US. In August 2021 she joined the Litro team as Book Review Editor, commissioning reviews of fiction translated into English. Other works can be found on her website:https://scribblatorium.wordpress.com