You have no items in your cart. Want to get some nice things?

Go shopping

Planning to read an unfamiliar book is always an exciting experience: The idea of entering someone else’s world, complete with unfamiliar characters revealing their uniquely unfamiliar inner worlds presents a plethora of possibilities. Add to that an unfamiliar setting, especially a country like Iran that is usually presented as a pariah in news cycles around the globe, and where the information that reaches the general public outside that location is subject to question, and the anticipation of a heightened experience increases.

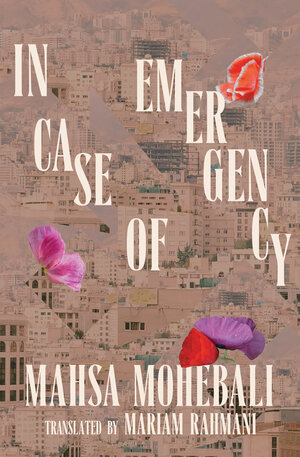

In all of these regards In Case of Emergency satisfies, and it is no wonder it won the prestigious Houshang Golshiri Literary Award in Iran – although given the focus on blatant counterculture functioning and the liberal use of expletives, it is perhaps surprising that it should have such appeal at home.

Lovingly translated by Mariam Rahmani, In Case of Emergency (which is called Don’t Worry in the original Farsi), clearly conveys the dystopian, bizarre world into which we are plunged and for much of the book it is easy to forget that it is a translation, the work is so smooth. There are, however, many phrases that are probably familiar to Farsi speakers but which in lacking translation, can feel disconcerting. What, for example does “Ya abolfazl” mean? And what does it mean when used in a given context by a particular character? This could be easily remedied by translations below the text or in an appendix, as with such out-of-the-ordinary characters it would be helpful to know everything they say – as even simple phrases heighten or change the mood.

Immediately plunged into a weird and surrealistic world where the characters are the antithesis of the people by which most of us are surrounded, we are immediately taken out of our comfort zone. The protagonist, Shadi, is an affluent, bored but educated heroin addict, crashing from strange place to strange place, in a society that seems to be falling apart and a nation that appears to be crumbling. She wanders the city disheveled, dressed as a man and eschewing everything remotely feminine through vulgar language and a course turn of phrase. Friends suffer from “dick deficiency” and live in a “shithole country” (and this was written well before Trump adopted the phrase!) in a revolt that is as much verbal as it is physical against the traditional feminine role. Indeed, this rebellion extends into everything Iranian and Muslim with the result that we are unsure who is who and what is what, in a fascinating plot which – unusually – unfolds in a single day.

In the space of 24 hours, Shadi interacts with her dysfunctional family members, goes into the street and connects briefly with an array of other strange characters: one with snot dribbling from his nose, a crying infant whom Shadi picks up but doesn’t seem to relate to, and a potential suicide victim whom Shadi may or may not have rescued in her search for her next “fix.” Who or what else needs to be fixed? Maybe it’s the protagonist’s mother, a bona fide prima donna, who belts out arias in the most unexpected locations. Is this colorful character high on some substance we are not informed about? Is she mentally ill or suffering from a disease like Alzheimers which afflicts Shadi’s grandmother? Or is she, like so many characters in this novel, a metaphor for a type prevalent in a society we know so little about, representing perhaps the dysfunctional maternal figure, more concerned with her own needs than with those of her daughter? Or is she simply an older woman whose place in the modern world is no longer as treasured and respected as it once was? The reader is left to figure it out alone, the only creature in this work who proves at all consistent being a dog named Crassus. The dog is constant, caring, and protective of Shadi. Is it some sort of canine metaphor for the strong and caring male? Or perhaps, as Sigmund Freud once said, “sometimes a cigar is just a cigar” and animals feel easier to read than people.

Certainly, this book raises more questions than it answers, and the reader is left feeling like he or she has just plummeted down the rabbit hole in Alice in Wonderland or been thrown around on a roller coaster that has slipped off the rails. An essay, “The Half Human,” written by Mohebali in 2013 when she was a resident at the University of Iowa, may shed further light on what this book is about. In it, the author writes poignantly about what it means for a woman to be considered “one-half of a person.” Focusing on the legal and social, she goes on to describe the many ways in which this definition of women is true in Iran: “We get to be Barbie dolls at home, we make sure to have nose jobs and breast implants; we inject silicone into our cheeks and lips . . . we do all this to forget that we are not complete.” She also discusses the attempts to remedy this by revolting, (as Shadi does), and then discusses writing as another form of rebellion, through which freedom is easier to achieve than it is in the home. In this essay, Mohebali also refers to “Persia with its pompous cultural heritage,” implying that the weight of that illustrious past is part of what is weighing her down, weighing all women down until they are seen by society in general, as more than just half-people, but half-human.

Iran on the whole gets quite negative press and has been subjected to considerable economic sanctions. I have been told by people currently living in Iran that In Case of Emergency is representative of a genre of literature that was produced shortly after the revolution, in the early two-thousands and is about a time of misery and defiance. It is often referred to as “the genre of suffering,” “the genre of resistance,” “or “the genre of having a grudge against religion.” It captures a time of breaking norms but of not knowing what is to come. While the youth involved in the general national scene at that time were not actual revolutionaries, they were keen to disrupt cultural, religious and societal norms beneath an ever present threat of prison.

In this novel, certainly, nothing is right, everything about the old way is dismissed and the people are rejecting all that came before. Earthquakes abound and for those of us who have never experienced an earthquake it is hard to appreciate just how destabilizing they can be. We expect many things in our lives but the earth rolling and moving beneath our feet is not one of them. Shadi’s world is clearly falling apart and there is no guarantee that tomorrow will be as yesterday once was. As such, she searches for answers but if she rejects the past, what else can there be? Religion does not seem important although the story does open with someone listening to digital prayer beads, which is perhaps emblematic of a more generalized search for what might replace a once glorious, but now rotten past. Women in chadors are referred to as “clawing at each other,” whilst at this “end of the world” in which she finds herself, “there’s no mercy, even for Muslims.” So, whilst religion might remain, it is not an especially positive force.

As Shadi wanders Tehran, dirty, disheveled and looking almost as if she were going to live in the woods or join a paramilitary group, there is only one occasion on which her near total rejection of the traditional, female role is abandoned. When her good friend threatens again to commit suicide, she rushes to his flat to save him, not sure whether or not he needs saving, since he has threatened suicide previously. And as she ministers to him, she expresses frustration at having to help in this way, resenting her instinct to come to his aid. Does Mohebali regard the nurturing role, then, as now a waste of time? Or perhaps she sees it as counterproductive in the new Iran that she envisions? There is a sense here that everyone is more or less suicidal, and that nothing now matters, not even – or perhaps especially – life itself. It is an alarming thought.

This is a fascinating look at a proud country that has been stigmatized and isolated for many years. Mahsa Mohebali has very skillfully produced an anti-heroine who goes against convention and eschews much of the old, but who hasn’t yet found exactly what it is she can put in its place.

In Case Of Emergency

By Mahsa Mohebali

Translated from the Farsi by Mariam Rahmani

The Feminist Press, 168 pages

Mandy Brauer

Mandy Fessenden Brauer is a retired American clinical child psychologist who taught at the American University in Cairo and with a Fulbright at Cairo University Medical School. She’s published numerous picture and story books in Arabic and English in Egypt to help kids understand themselves and their world better. She’s also published books and articles in Egyptian magazines on parenting children in conflict zones and those seriously ill as well as published books for adults and children on preventing, identifying and treating child abuse. An illustrated poem, Goodnight My Cairo sold over 22,000 copies and is being re-illustrated. Her poem, “Celebration in the City” was made into a performance piece at The Mattress Factory in Pittsburgh, Pennsylvania. More recently an article about living in Gaza during the first intifada was published in New Moons: Contemporary Writing by North American Muslims, published by Red Hen Press, November, 2021 and currently she’s working on stories and essays about the Islamic World for adolescents. When she’s not doing anything else she’s thinking about what to write next or going for long walks along the Nile if she’s in Egypt or strolling through rice paddies in Indonesia since she, her husband and two senior cats now divide their time between these two fascinating countries.