You have no items in your cart. Want to get some nice things?

Go shopping

The Woman from Uruguay, the latest novella by Pedro Mairal, has left me with mixed feelings. Although I enjoyed some aspects of the prose, it failed to meet the high expectations built up around it prior to its translation into English. In fact, until I had relieved myself of all I had heard about it before it came into my hands, I was quite unable to find the proper perspective to review it.

The Woman from Uruguay was first published in Argentina in 2016 and quickly became a best seller in Latin America. It tells the story of Lucas Pereya, a middle-aged writer from Buenos Aires, who, “defeated,” as the narrator confesses early on, and wretched with how his life has unfolded, falls into the trap of a sexual fantasy. As the story opens, Pereya is embarking on a ferry to Montevideo to cash out a book advance he has finally obtained. He hopes the money will buy him time to write a new book and settle his debts. The funds would also make his wife happier and ultimately fix his marriage. On the way to Montevideo, Lucas confesses about Guerra, a Uruguayan woman he met a year before and has fantasized about ever since. Unfortunately, his intentions to save his marriage are instantly clouded by his desire for this woman he knows little about. His desire becomes increasingly powerful as the day progresses, not only obscuring his mind, but his senses too. When he does finally meet up with Guerra, he loses control over his ability to reason. The narrator confesses the affair to his wife in the form of a letter in which he lies to her repeatedly. Both women in the story are objectified and never given a proper space in which to grow as characters.

The central themes are a bag of money representing salvation, liberation from the claws of marriage and childcare, and the sexual freedom of a middle-aged man. Put them all in a pot, and you get a sour taste of patriarchy.

Fifty pages in, and we already know that the money and the fantasy girl will be gone on the very same day, perhaps even together. Mairal skillfully creates urgency in the prose that keeps his readers engaged, but the way the story unfolds is entirely foreseen. The narrator moves through a continuous stream of events that happen to him but don’t change him nor move him forward. The way the concept of desire is treated in this work reads as banal and predigested. It is only through hard work that I uncovered a second layer of the work, a kind of a meta-text that has nothing to do with the failing marriage or the flat love affair, but which represents a discourse on writing. This is the only aspect of Mairal’s work I was drawn to and engaged with. I read it as autofiction, as the author’s confessions about his own writing life. Lucas Pereya is a writer who hasn’t been writing. The complex marital situation and the fact he has been raising a child are excuses for the depression the narrator has been struggling with. He has been short on ideas, at war with critics and unable to process rejection – a topic that will appeal to thousands, especially writers. Haven’t we all found ourselves in a similar thought pattern? Haven’t we all reached for excuses?

As the book reaches its climax, the narrator finds his old writing mentor in Montevideo, to whom he confesses the true meaning of the money: “It wasn’t a debt, it was time, the money was time to write without having to take another shitty job,” to which his mentor replies: “The books have to be written, that’s the first step, and then you decide how much they’re worth.” But Lucas continues his repetitive lament: “How am I supposed to write with my kid dangling from my balls, reading ten thousand students at once, teaching classes? How the fuck am I supposed to write like that?” And this is the crux of this novel. I thought for days about Mairal’s authorial intention. Is this supposed to be a well-versed criticism of the figure of a privileged male writer who believes that his God-given talent is enough for success? Or does the author himself feel sorry for Pereyra’s “struggles”? If the first thought applies (as I hope), then I am relieved. Yet I closed the book disappointed to see Pereya unchanged and even more despicable than he was to begin with. I closed the book having skipped over the narrator’s (or the author’s) dull macho ramblings about Pereya’s newest sexual pleasures. The concept of the alpha male and the objectification of women simply worsened towards the end. Pereya’s wife leaves with another woman (God-forbid that another man be allowed to touch her!), and Guerra ends up with a child in a polyamorous marriage. Does this choice of setup make the narrator less of a loser?

It is two weeks now since I read the book and I am still wondering: What if this was a story about a woman writer? Would she even be allowed to fantasize about money to “buy herself time”?

By Aleksandra Panic

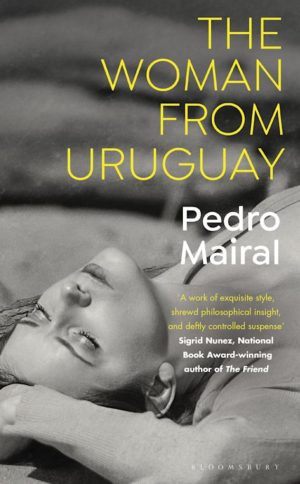

The Woman From Uruguay

by Pedro Mairal

Translated from the Spanish by Jennifer Croft

Bloomsbury Publishing, 160 pages

Alexandra Panic

Alexandra Panic is a Serbian-American writer, teacher, and astrologer. She is currently a Ph.D. student in Transdisciplinary Studies in Contemporary Art and Media at the Faculty of Media and Communications in Belgrade, Serbia. She holds an MFA in Creative Writing from Goddard College and a BA in Italian language and literature from Belgrade University, Serbia. She is the managing editor of Pif Magazine (www.pifmagazine.com) and the founder of Flower Moon Practice (www.flowermoonpractice.com).