You have no items in your cart. Want to get some nice things?

Go shopping

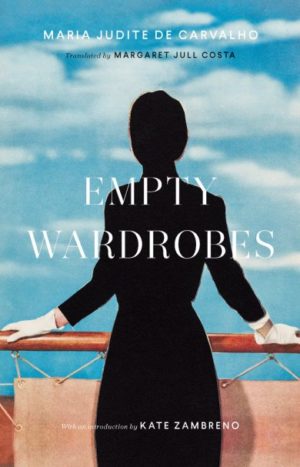

Originally published in 1966, Empty Wardrobes is a novel by Portuguese writer Maria Judite de Carvalho. Translated into English this year by Margaret Jull Costa, its timeliness is both enlightening and depressing. In this brilliantly simple story, de Carvalho shows us how the actions of two men upend the lives of three generations of women due to long-standing patriarchal constructs.

Dora Rosario is a widow and mother to Lisa, whose late husband left her with no money or prospects. Dora, with the support of some friends, manages to find work running an antique shop, which Lisa refers to as the “Museum.” In order to make ends meet, Dora spends her days feeling old, surrounded by old things. The shop is filled with “glass domes covering beautiful clocks that had long since stopped, images from the eighteenth century, ornate boxes, exquisite, elegant ivory figurines,” and Dora dresses as “Salvation Army Dora” – that is, in drab clothing meant to mourn her husband. But after 10 years of grieving, Dora’s mother-in-law Ana drops a bombshell: Dora’s husband Duarte had been planning to leave her for another woman. Armed with the awareness of many years wasted, Dora seizes on an opportunity to remake herself.

Kate Zambreno notes in the introduction: “This is a hilarious and devastating novel of a traditional Catholic widow’s consciousness, encased like ambered resin in the ambient cruelty of patriarchy, an oppression even more severe in the God, Fatherland, and Family authoritarianism of the Salazar regime in Portugal. A work like this, set in the regime of a dictator who weaponised Catholicism and ‘family values,’ is by its very nature deeply political.”

It is political because it starkly paints the fallout of women in a society that expects strict adherence to traditional roles. Dora’s husband, like most husbands in post-war Western society, expected her to remain at home and raise their daughter. Dora abides, but her husband does not follow the rules for men. Instead of providing for his family, he prefers to get by doing things he enjoys and avoiding hard work: “This was perhaps the sole activity, if you can call it that, to which he had gladly devoted his life – to being nothing.” The lesson Lisa takes from Dora’s life is that she must marry a rich man while she’s young and beautiful. She tells her mother, “We young people know that youth doesn’t last very long, and you have to make the most of it because, by the time you’re thirty, it’s all over.”

The novel traces Dora’s transformation from lifeless widow to adulteress. Dora does not so much pursue Ernesto as she allows herself to be in the right place at the right time. It is a test – of her attractiveness and of her own audaciousness. After all, she had just overheard her teenage daughter describe her as “both ageless and hopeless.” It is Lisa’s brutal assessment of her mother’s life choices that prompts her down a new path.

While the novel centers on Dora’s life and family, it is Manuela who arguably suffers the most. An apparently peripheral character, she narrates the novel and ultimately takes centre stage. She also knows Dora’s story intimately, with the benefit of objectivity: “Some people got religion or killed themselves after losing someone, whether that person died or just left them. Dora Rosario, however, didn’t blame anyone else for her misfortune. Only herself. She loathed herself, but not enough to seek relief in death. No, she simply disliked herself, a more modest sentiment. And when, for example, she was standing before the mirror to apply her lipstick at the very moment Ernesto Laje came into the shop, doing so had given her no pleasure; indeed, what she felt was a degree of discreet rage.” Could that rage have been some version of The Feminine Mystique, the 1963 book by Betty Friedan that exposed the unhappiness of housewives? Here is the moment, deftly drawn by de Carvalho, when Dora sees her life with disturbing clarity – a wasted decade, a wasted marriage, and now, at 38 years old, her options have dwindled from limited to nonexistent.

Manuela incisively recounts the events that lead to her partner Ernesto’s desertion, noting: “It seemed to me that the name of the problem wasn’t Manuela, but he’d found a way of making me the problem. He was unhappy because I’d failed to bear him any children, so he was obliged to look for compensations elsewhere.” Manuela does not quite adhere to the rules of the Western world at that time; she is not married to Ernesto, and she never had children: “The truth is, it had never really bothered me, not having children, I mean. And would it have changed things if it had, I wonder.”

Manuela is a wise narrator with the clarity of hindsight. We don’t detect bitterness so much as apathy – she has probably wasted as many years as Dora had with Duarte, and what are these women left with, for all their sacrifices and willingness to look the other way? Dora is “a gray woman, slightly bent, lost in a plundered city deserted after the plague” while Manuela views the “old and ailing sky, bleary-eyed and weary with life.”

A call to arms for second-wave feminism, this novel shows us women who see their restraints but struggle to reach beyond the men and political institutions that uphold them. A timely translation, for although the “happy housewife” roles demanded of women in Empty Wardrobes may seem out of date, the need to break down patriarchal control remains.

Empty Wardrobes

by Maria Judite de Carvalho

Two Lines Press, 208 pages

Monica Cardenas

Monica Cardenas is a writer living in the U.K. She holds a PhD in Creative Writing from Royal Holloway, University of London. Originally from Washington, D.C., she earned a BA in English from Wilkes University, Pennsylvania. Her novel-in-progress The Mother Law was longlisted for the Lucy Cavendish College Fiction Prize and runner-up in the Borough Press open submission competition. Her writing appears in Litro, Sad Girls Club Lit, and Catatonic Daughters.

- Web |

- More Posts(3)