You have no items in your cart. Want to get some nice things?

Go shopping

I have always been curious about how adults arrange their lives, especially their lives within the walls of their homes, which is why I found myself fascinated by the story my buddy Packy told me a few weeks back about his friend Veratina. It seems that Veratina saw a psychologist for over thirty years and became quite tethered to the man, which didn’t surprise me because thirty years is a lot of therapy, even though I can’t say that for a fact because most people don’t talk about their therapy – at least not the people I know – and is another thing I’m very curious about. But then the psychologist, who was in his early seventies, died of a heart attack, his brother put the house on the market, and Veratina bought it.

Packy had told me the outline of this story in The Palace Diner, where we have lunch once a month, but he didn’t go into the details. Packy’s my best friend. We talk about everything, even though the conversation tends to focus on our health and what we will do when we can no longer manage the demands of our own homes, which I hadn’t thought much about until I injured my lower back a few months ago, couldn’t pick up my newspaper, and watched the pile of Globes on my doorstep get bigger and bigger. We’d just sat down yesterday when Packy said: “My wife and I had dinner with Veratina last week.” Packy is six-four, his moustache is the same reddish brown as his eyebrows, and he had a sharp tan line around his eyes from a recent fishing trip with some buddies.

“Where?”

“At her new house.” He took off his sunglasses and put them next to the ketchup bottle. The skin around his eyes was pale and he had a bar of white, like a piece of chalk, across the top of his nose.

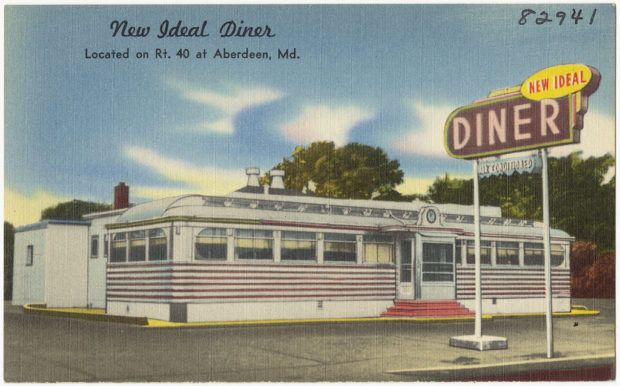

I put down my menu. We were sitting in the back booth at The Palace. A few feet away, Chet, the short order cook, was flipping hash browns and Labelle was making a milkshake. I love The Palace. It’s a busy diner, with casual booths on the left and a long counter with blue stools on the right. Metal lamps with large yellow bulbs hang low over each booth, filling them with a warm light, and there’s a bank of blenders, coffee machines, and coolers behind the counter. I said: “You had dinner at the dead psychologist’s house?”

“It’s not a dead psychologist’s house. It’s Veratina’s house now.”

“So, how was it?” I couldn’t hold back my fascination. Here was a woman who’d shared her most intimate feelings with a man for thirty years, he’d died, and she’d moved into his house. What was it about him and his house that made her want to do that? What did she think would happen inside those four walls?

“Fine.”

I waited for Packy to say more, but he looked hesitant, as if he felt guilty about sharing Veratina’s story. I unfolded my paper napkin and put it in my lap. The Palace uses thick paper napkins and that’s one of the many touches that gives the diner a homey feel. “Where does she live?”

“In Springfield. Just off the interstate.”

“Did you tell your wife the story of the house before you went for dinner?” I paused. “I mean, to give her a heads-up?”

“No.”

That surprised me. “You didn’t warn your wife that Veratina had bought her former psychologist’s house?” Packy tells his wife everything. I don’t have a wife or girlfriend, and my sister cut off contact years ago, so Packy’s the person I talk the most to. We grew up in the same town, went to school together, and have been friends for almost fifty years.

He shook his head. “Nobody knows about it.”

“The real estate agent and Dr. Van Meter’s brother weren’t aware?”

“Nope. Veratina is extremely private. Her only friends were the psychologist, plus my wife and me.” Packy closed his menu and slid it in the metal holder. “She doesn’t go to church, doesn’t belong to a gym, and has few connections. It’s hard for her to get close to people.”

“What’s her job?”

“She works in a lab, like you. It’s pretty solitary.”

Our waitress showed up with two glasses of ice water, a slice of lime in mine. “Hello, fellas. How’re we doing today?”

“Hey, Sylvia,” I said. All the waitresses at The Palace know us, which is another reason I like the diner so much. Sylvia is in her forties, arranges her grey-blond hair in a high ring that reminds me of a fluffy halo, and wears black clogs. She’s very familiar with my culinary likes and dislikes, especially my aversion to raw onions. In my opinion, to be able to go out to lunch, sit in a cosy diner, and have the waitress hold the raw onions on your lunch order without being told to is as close to home cooking as a person can get.

“Fine,” Packy said. “How about you?”

“Can’t complain.” Sylvia tapped her pad and looked at Packy. “Same thing as last Monday?”

“Sure,” he said. “Why not?” Packy has invited me on numerous occasions to join his weekly lunch with his fishing buddies, but I have always declined. I’m not a big fishing fan.

She smiled at me. “You want the regular?”

“I’ll try the corned beef hash, with two poached eggs.” Regular for me is a tuna melt with Swiss cheese on whole wheat, but for some reason, Packy’s story had put me in a daring mood.

“Eggs on top?” Sylvia stood a few feet away and crossed her arms. I could smell the lilac in her perfume. I have a soft spot for lilac. My mother used to put on lilac perfume for my birthday.

“On the side,” I said. “With rye toast, please.”

Sylvia left. I took a sip of water and refolded the napkin in my lap. “So, tell me about Veratina’s place.”

“I feel like I’m betraying her. Maybe I shouldn’t have told you the story.”

“Oh, come on,” I said, feeling a twinge in my lower back. My lower back has become the first place in my body that registers any change in my mood. I sat up straight. “It sounds like a fascinating story. Besides, who would I tell?”

Packy couldn’t dispute my second reason, and he must have wanted to talk about Veratina himself, because he aligned his placemat with the bottom of the table and said:

“It’s in a quiet neighbourhood.”

I nodded. “I would think so. A psychologist would want a quiet place.”

“How do you know that?” Packy didn’t ask his question in a negative tone, but my comment seemed to surprise him.

I shrugged. “Psychologists must need peace and quiet to do their thinking. Did Dr. Van Meter have a family?”

“Just a wife. She died in her fifties.”

I thought about that. Dr. Van Meter lived in a house with the memory of his dead wife, and now Veratina was living in the same house with the memory of her dead psychologist, plus the psychologist’s memory of his dead wife. It felt almost too complicated to ponder, which surprised me because I spend a lot of time by myself pondering all sorts of complicated things. I said: “So what happened?”

Packy arranged his knife and fork in front of him. “We sat in the living room, had a drink, and chatted about the weather, real estate taxes, and why people don’t use their turn signals when they drive.” Packy glanced at Chet, who’d just slapped a hamburger on the grill. “Veratina rides her bike to work. She said that drivers who don’t signal are a menace.”

I was going to tell Packy that my sister probably commuted on her bike, too, but since I didn’t know where she lived, I couldn’t say that for sure. I said: “How was the dinner?”

Packy took a sip of water. “Veratina made lasagna and a nice Caesar salad. She gave my wife the recipe. You want it?”

I laughed. “You know me and cooking. I’m lucky if I can whip up a plate of hot dogs and beans. So…you ate and then you went home?”

Packy shook his head. “Then Veratina gave us a tour.”

*

Sylvia returned with our lunches. She put a hamburger and fries in front of Packy and served me the corned beef hash. As soon as I saw my plate, I knew I’d made the right choice. Even though I’d taken a risk ordering poached eggs because they often come out runny at the other diners I eat in, these looked fine, plus my hash shone with an inviting veneer of crunchy fat. Sylvia motioned at our plates. “Can I get you fellas anything else?”

I pointed at the bulletin board behind the counter. “You’ve got a new post card.” A few years ago, The Palace put up a board so their regular customers could send cards from the places they travel to. I love looking at that bulletin board. One of my harmless fantasies is to sneak in The Palace one night and read what the regulars wrote to Sylvia, Chet, and Labelle.

She looked. “Which one?”

“See that card next to the Washington Monument? It’s new.”

“I’ll ask Labelle.” Sylvia smiled at me and then said something I wasn’t expecting: “Would you like to send us a card?”

“Me?”

“You always notice the post cards.” Sylvia gave her halo of hair a delicate pat and

nodded at the board. “There’s room for you.”

“The problem is,” I said. “I don’t go anywhere.”

“There must be someplace you want to visit.” She smiled at me. “I’ll write the diner’s address on your check.”

After she left, Packy said: “Why don’t you take a trip? You can send a bunch of cards to folks.”

I laughed. “Who would I send cards to, besides you and The Palace?”

“You could send a card to your sister.”

“I don’t know where she lives. And even if I did, she’d throw it out.”

*

We tucked into our meal. It was quiet in our booth, except for the clink of our forks and knives. After a time, Packy put down his burger and wiped his lips. “We started in the kitchen.”

“Modern?”

“The stove and dishwasher looked at least ten years old, but Veratina bought a new refrigerator. The cabinets were new, too, with pull-out shelves where she kept her pots and pans.”

“Any family photos on the refrigerator?”

Packy shook his head. “Veratina doesn’t have a lot of family.”

“She must have some photos.” I don’t know why I said that because I didn’t have any photos in my apartment either, and besides, I knew nothing about Veratina. “Where’d you go next?”

“She led us back to the living room, where she pointed out the bay windows, which were six feet wide; the fireplace, which had small blue tiles around its border; and the mahogany bookcase. Then we went into the dining room, where there was a chandelier and a corner cabinet.”

“Any china in the cabinet?”

“No.”

By now I had to admit that I was obsessed with Veratina’s house, but I still hadn’t seen the thing I was looking for, even though I didn’t know if such a thing existed. Maybe it didn’t exist. Maybe Packy was telling the truth and Veratina just wanted to live in the house that her devoted psychologist of thirty years lived in. “Next?” I said.

The three of them went upstairs. Packy described the master bedroom, with its plush green carpet, the two bedrooms in the back that looked out on a sycamore tree, and the bathroom with its tub and walk-in shower. He described the pull-down ladder for the attic and the cedar closet in the master bedroom.

I said: “Did Veratina sleep in Dr. Van Meter’s old bedroom?”

“Archer, that’s not what this is about.”

I stared at him. I had to ask the question that had been in the back of my mind ever since he’d brought up the story. “Veratina wasn’t in love with Dr. Van Meter?”

“Absolutely not,” he said in a firm voice.

“How do you know that?”

Packy shifted in his seat. “Dr. Van Meter provided a lifeline for Veratina. Thirty years of support, understanding, and compassion for a woman who had great difficulty getting close to other people.” He paused. “They had a special relationship and Veratina wanted to honour that.”

“She paid for the relationship.”

“Yes, she did,” he said in a vexed tone. “But that didn’t make it any less sustaining. At least Veratina could make a connection with someone.” When I didn’t respond, he said: “So you don’t agree that everyone needs close bonds? That we all need people we can share our inner thoughts with?”

“Not like that.”

He ate the last of his French fries. “That’s enough of the house tour.”

“No, keep going.”

“I should stop.”

“Finish the tour!” I said a loud voice.

At the grill, Chet turned around and stared at me, his spatula suspended at shoulder height. The busboy, who was three booths away, looked up. I lowered my voice. “Finish…please.”

I’ve shouted at Packy in the past, but I would never do that in The Palace. The last time I yelled at him was when he signed me up for a men’s group at his church. The time before that was when he sent me information about his book group, which I promptly threw out. Sometimes I think the only reason Packy has remained my friend is because we go back so far. We visit our hometown several times a year, even though my parents are long gone and strangers have bought their house. Many things happened in my house when I was growing up and, as I’ve gotten older, I find myself thinking about them more often, though I don’t understand why they took place or why they made me arrange my life as I have. Once, I knocked on their door, but no one answered.

Packy finished the tour. He told me how he, his wife, and Veratina went down to the basement, where Dr. Van Meter’s brother had left behind the woodworking bench. Apparently, the doctor was quite a woodworker and used to make gifts for friends and family.

“So that was when your wife figured it out?”

Packy nodded. “Veratina basically told her.”

“Did your wife ask her why she bought her former psychologist’s house?”

“Yes.”

“What did she say?”

“She said the house was in a good neighbourhood, it was close to her job, and it made her feel connected to Dr. Van Meter.”

“So that’s all it was about? Connection?” I got out my wallet to pay. “It wasn’t more than that?”

Packy started to say that people shouldn’t underestimate connection, especially folks whose lives were solitary, which made me interrupt him and say that food and shelter were more important than connection.

“I’ll grant you that,” he said in a voice that was half subdued and half irritated, but after the basics, he went on. “It’s connection we all hunger for, even people who have trouble getting close to others and act if as if it doesn’t matter,” which was a criticism of me and made me want to raise my voice at him a second time, right there in The Palace. But God bless Sylvia because just then she showed up and said: “You fellas going to order dessert?”

“What’ve you got?” Packy said.

“We have some nice pies today.”

“That’s a great idea,” I said. I love all the food at The Palace, especially their pies. I love their blueberry pie, their apple pie, and their strawberry rhubarb pie. I even love their pecan pie. The problem was that I honestly did not know which pie to pick. But then I had an idea: Why not let Sylvia decide? She knows my likes and dislikes, right down to the lime in my ice water, and she’s never disappointed me. I like all the staff at The Palace, even the busboy and the part-timers, but I would have to say that Sylvia and I are the closest of all.

James English

James English’s fiction and essays have appeared in publications such as The Healing Muse, Baltimore Review, Glimmer Train, Florida Review, Sonora Review, and Education Week. He has worked in education for much of his life and has degrees in French and Spanish. He is working on a coming-of-age novel.