You have no items in your cart. Want to get some nice things?

Go shopping

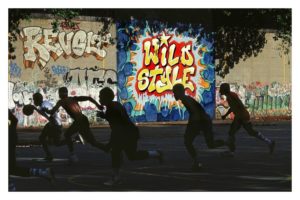

In your incessant scrounging and scavenging, you manage to find the best talent. You started surveying in New York amongst poor Blacks who brought their blues, jazz, and spirituals to the city of rectangular skyscrapers. You realized the country’s deindustrialization would leave excessive numbers of Black Folk, especially young men, unemployed, who in their idleness began to draw on the West African griots, spoken word, and call and response. Add to the mix immigrants from the West Indies and Latin America’s Caribe with their distinct takes on African drumming plus the need for a new generation to create an identity other than mainstream pop, and hip hop was born.

Yet you were not content. This was New York, USA, and profits had to be extracted. You reckoned hip hop was cute, but you speculated it was mere dalliance, a ride in Central Park. And hip hop, with its cultural linkage to Slave Songs and Civil Rights chants, with its critique of both material wealth and the colonization of Blacks in America, with its sprinkling of young women trying to test their talents in its hypermasculine verbal boxing ring, didn’t sit right with the money makers ready to scavenge the talents of disaffected young men being sidelined by an economy that increasingly had no need for muscular brawn.

As corporate rap, you aligned yourself with white supremacy and patriarchy, and in the contract, you specifically stated that the addition of funk, rhythm & blues, soul, and rock & roll were acceptable only if the old tradition of the minstrel shows hovered in the wings. Minstrelsy, which started historically with whites in Black face, was opened up to Blacks who were compensated for entertaining bespectacled whites who sat and marveled at the talents, constant innovation, and buffoonery of Black people. The catch: the lyrics, imagery, and lifestyle of the rap artists had to subtly communicate that the neoliberal project of rugged individualism in a deindustrialized service economy was really o.k. Sex and partying had to be emphasized so the music could be used to release the pressure valve of constant work for little return that was being imposed on the entire nation. If the message was on point, the economic rewards to Black artists (as well as non-Black hangers-on) who crossed over and went pop would be unlimited.

You scoured and rummaged. Philadelphia. Chicago. Detroit. The Dirty South. Los Angeles was the gem. Not only was L.A. enlisted to create a notorious rivalry with New York, it was also linked to the Feds’ desire to plant Central American cocaine in the hood using gangsters already on the ground. It was the Fed’s scheme of killing two birds with one stone – fund counterrevolutionaries in Central America while wrecking hellish havoc on Black life in L.A. All to the beat of a drum.

You’ve left no stone unturned in your intention to commodify Black culture. Clutching with one hand speculative capitalism and with the other gentrification, you’ve extracted talent and heritage from geographical regions and Black neighborhoods while simultaneously demanding that both disappear.

P.S. – Say sunthin. You wanna say sunthin. Get sunthin. You tryne to get sunthin. Shake sunthin. You tryne to shake sunthin. Cuz the stripper that set the beat said you trippin on yo feet if you tryne to take sunthin. All the whips at the crib, all the commas in the bank, all the Benjis in yo face gone make you do sunthin.

AUDREY SHIPP

Born in Los Angeles, Audrey Shipp is an essayist and poet whose most recent writing appears in "Linden Avenue Literary Journal," August 2018 and "A Gathering Together," Spring 2018. Her bilingual and trilingual poetry appeared in "Americas Review (Arte-Publico Press)" which was formerly published by the University of Houston. She teaches English and ESL at a public high school in Los Angeles.

- Web |

- More Posts(7)