You have no items in your cart. Want to get some nice things?

Go shopping

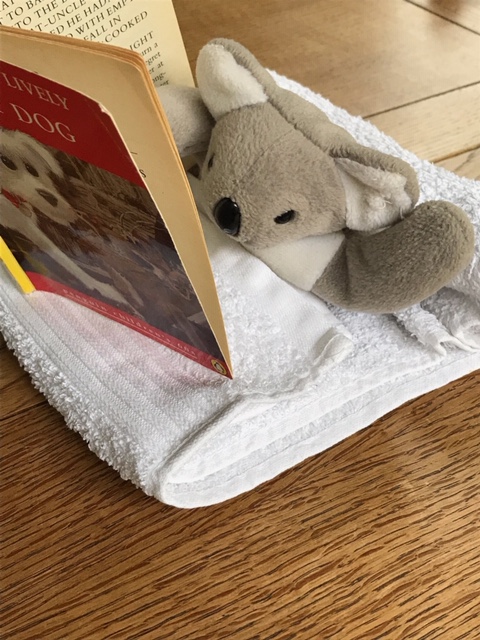

Photo Credit: Charles Rattray

He wonders whether it was the child or the old man in him that led him to do it, or whether it was the sentimentality that he would mock in anyone else, the sentimentality that cropped up more frequently as years passed. Why else did he look in the sewing box, the box that he, in a sexist fashion that he was always quick to condemn in others, referred to as his wife’s sewing box, why else would he have taken out that particular object? Who knows when the children last played with the bean-bag toy? It must be at least twenty years since his wife had put it in there with the intention of stitching back the side of the head, where a thread was still hanging loose. Twenty years is a long time and yet how quickly those years have passed, the years in which the children have left home and in which he has become old.

He listens to the silence, the bright silence of that late afternoon in August, the light still blazing through the French windows he had designed such a long time ago. The pleasure of solitude. For the first time in many years he experiences a sense of freedom. It is a feeling he likens to the days when he was young, the days before commitments and lasting relationships. Back then the feeling was accompanied by a conviction that the world was his playground. He recalls the fluttering in his chest, the flutter of restless energy that signalled infinite possibility. The memory of the flutter evokes nothing but the painful realization of its absence. This is the freedom of an old man, blank and content but dull and aimless. The pleasure of solitude turns into a pang of loneliness. Is he lost without duty and obligation? He never suffered from ambition but most of his adult life he felt constrained by the daily grind of work and the demands of his family. He had dreamt of the time when he would be free to indulge in his creative side, free to draw imaginary buildings without worrying whether they were viable projects. Now he has all the time in the world, but no burning desire for anything, and needs persuading to enjoy the moment: a glass of white wine, only slightly chilled, should help, temporarily. He contemplates the patio behind the window, the neat sculpted arrangement of greenery in terraced beds. A perfect picture, he reminds himself.

Nothing moves. All is still and silent. A vaguely-remembered sentence from a vaguely-remembered play comes to him: the world must be uninhabited. It might be because he hasn’t spoken to anyone for almost twenty-four hours, or an effect of the wine, on his empty stomach, that makes him light-headed and he experiences a strange sensation of time stopping. For a moment, he thinks he watches his body levitate. What scares him is not the sensation of it happening but the sight of his frailty. For the first time he sees himself as an old man.

He stretches and blinks several times to shake off the sensation. A few deep breaths. His eyes closed. Squeezed and opened. Again. Alert, he reaches for the paper. The same old news of the quagmire of national politics. He turns the pages of each section without reading them. Another sip of wine. Years ago, he would have thought “that’s the life”: sitting with a glass of wine, reading the paper on a summer afternoon in his beautiful, bright kitchen. Until he was old and retired, he didn’t know the meaning of desultory. Unguided by any definable intention, his body stands and walks to the cupboard opposite the window. He listens to his steps, welcoming anything that might shut out the silence that threatens him. The impervious silence of an indifferent world. His hand opens the middle door in the bottom row and pulls out a rectangular wicker box. With no hesitation, he lifts the lid and there it is: the small bean-bag toy. If he were to stop to think, he would have asked himself how he knew the toy was there. How come he isn’t surprised to see it? He holds it with his thumb and index finger, turning it around as if to inspect its condition.

He brought it back from a conference he attended in London and where he had had a fling – hardly an affair, just a two-night stand – with a woman who he had known by name from the articles she had published. She was a small, rather plump brunette, dressed in black, except for her shoes. He remembers being struck by the size of her feet. Nine, the same as his. While their bodies were still entangled, out of the corner of his eye, he caught sight of her hastily discarded red stilettos by the side of the bed. He hoped she wouldn’t take much longer and bizarrely – later the thought used to make him smile – not because he was losing it and feared slipping out but because he couldn’t wait to inspect her shoes. She cried out and he was free to leave the bed. They fitted him perfectly. He tottered around the room on the heels, his penis bobbing up and down. Antonia, yes, she was called Antonia, laughed. He stood in front of a full-length mirror, staring at his front and then his back. Through laughter, she shouted, “belle gambe”. Her beautiful Italian. Before he tiptoed down the corridor to his own room, wearing his brogues, she thanked him for the pillow talk. He may not have been her champion at the main course but at least he received praise for the dessert. The second and last time, she had gone to her room ahead of him – they had to make sure not to leave together in front of colleagues – and by the time he arrived, she was lying in bed with her clothes and shoes all put away. They were warm towards each other, but they could not conjure the excitement of the first time. The pillow talk was all shop: she complained about her department, and he reciprocated. When he sat up and reached for his shirt, he noticed a bean-bag toy by her bedside. He smiled. Did she share his affection for soft toys? A woman after his heart, unlike his wife who made fun of his fondness for things small and fluffy. He picked it up and saw it was brand new; the price tag was still attached. “For my daughter,” she said. “All her friends have them.” A good idea. He thought she deserved credit for knowing the latest fad of her children. He couldn’t say the same about himself. Despite his protestations, she insisted he took the toy. A present from her. She would buy another on the way to the station the next morning. It was appropriate for him to have it. He was a koala. No one had ever held onto her in bed as he did. Like a baby koala clinging onto his mother. Obliging and needy at the same time.

Next day, on the way to the train station, he stopped at the shop Antonia had described – she had left much earlier – and bought two more of the toys. He couldn’t face the prospect of his wife sneering had he returned with just one. Having three, one for each of the children, was fine. He didn’t count on their preferences. Each said they were happy with either the puppy or the tiger but no one wanted the koala. His wife said the koala was the best; it was like daddy and she called him by his own name. Charles, the koala. He had a moment of panic. How did his wife know what Antonia had said? But the trick worked. The elder girl said she would love the koala and the dispute was settled.

Antonia died a few years ago. He read her obituary in the “Other Lives” section, written by a friend, a colleague who referred to her affectionally as Toni. He contacted the obituary writer – again he was familiar with the name from professional journals – to ask about Antonia’s death. He had expected it to have been cancer – she had been in her fifties – but received no confirmation. Instead, the obituary writer sent him the unedited version of the text. He learned that Antonia had a passion for soft toys. An architect with a passion for soft toys. Her large collection was left to a museum. She had no children.

For months he couldn’t stop thinking of her. Why was there no cause of death mentioned? A fellow soft toy enthusiast. Like him, one who didn’t dare admit it to the world. Like him, one who understood that everyone needed something that mattered, however insignificant to the world. She was his first marital transgression but he had never thought of her, just as he didn’t think of those who followed. He made sure nothing disturbed his family life though he attended conferences and took other opportunities with dutiful regularity. Betrayals – but he never thought of them in such terms – kept him alive. Today, other stories of his life flow back. He cannot tell whether they are memories or fantasies but Antonia is the only one whose name he remembers. Toni, as her friend referred to her, poor Toni is dead. Her soft toys are in a museum. What happened to those beautiful shoes?

With no cause of death mentioned, he suspects it is suicide. Our culture still attaches shame to it. A remnant of Christian thinking in a secular society? He remembers reading somewhere that architects are the professionals fifth most likely to kill themselves. From Francesco Borromini onwards, throughout centuries. But their self-inflicted deaths are less publicized than those of writers. Everyone knows of Woolf walking into a river with stones in her pockets, Hemingway’s gun shot, or Plath’s head in a gas oven.

One day he will die too but the koala, as is in the nature of such things, will survive. He will make sure it is in mint condition. He could give it to a grandchild. If he ever has any.

It’s time to set about repairing the koala. He squints at the needle and it takes him several attempts before his trembling hand manages to force the thread through the eye. It feels like yesterday when he was a proud five-year-old helping his granny thread a needle. She struggled and struggled but he would succeed the first time he tried.

The koala lies inert in his palm as he stitches the side of its head. No anaesthetic but no complaints from the patient either. The operation is a success. The patient needs rest to recover fully. He takes a white hand towel and folds it to improvise a small mattress and a pillow. He tucks in the koala and props up an opened book in front of him. His is a learned koala.

And now all is done, he is fully free. Free to do as he pleases. But does anything please him these days? What to do? His growing hebetude is wearing. He has become someone he neither likes nor recognises. A lost old man, reeling from retirement.

But what if … what if … he did something. Something to make his retirement memorable? He has an idea. Its sparkle instantly energises him. When the night falls, he could take a taxi to the bridge furthest out in the estuary and jump in. It will take days before his body washes ashore. By that time, his wife will be back from her holiday. He wouldn’t want to have her to truncate it by the news of his demise. When she arrives, she will be with her best friend, no one better to offer her comfort as she finds out. He loved her all his life but he has nothing left any more. Nothing left to give except memories. What a sentimental old fool he is. He pours himself another glass of wine. He finishes the bottle and opens another one. He glances at the koala. Charles the koala, peacefully reading.

vesna main

Vesna Main was born in Zagreb, Croatia. She lives in London and in a small French village. Her publications include: a novel, A Woman with no Clothes On (Delancey, 2008), a collection of short stories, Temptation, A User’s Guide (Salt, 2018), a a novel in dialogue, Good Day? (Salt, 2019) shortlisted for Goldsmith Prize 2019, autofiction Only A Lodger … And Hardly That (Seagull Press, 2020) and novella Bruno and Adele (Platypus Press, 2020), republished in Shorts III (Platypus Press 2021). Her short stories have appeared in jorunals online and in print. Following on from Modernism, Main's focus is on exploring generic possibilities of the narrative. She lives in London.