You have no items in your cart. Want to get some nice things?

Go shoppingI.

“Have you ever heard of the poet Xu Zhimo?” asked Paul.

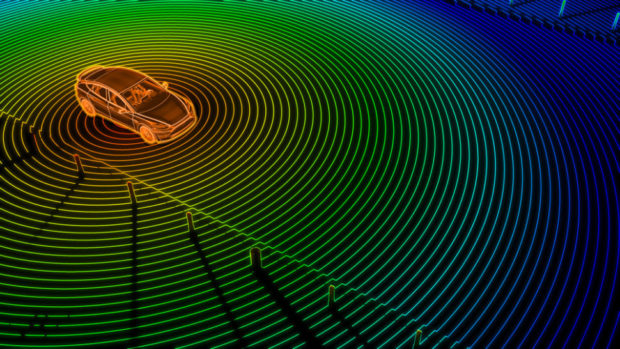

I hadn’t, nor was this a question I was expecting to hear from my Uber driver in a discussion about autonomous vehicles.

“A great Chinese poet, studied at Cambridge. The Chinese tourists love him. They go get their picture taken by the plaque over at King’s College. Problem is, it’s a big plaque, so they have to step back into the road to get a picture of it. So whenever I drive past King’s and see a group of Chinese tourists, I know I have to be on the lookout. Could a driverless car do that?”

Paul had a point. On the face of it, at least, being able to anticipate a pedestrian’s behaviour like that would require not just quicksilver silicon reflexes, but the ability to get inside their head, to understand their motivations, their goals, the reasons for their actions. In other words, to tell a story about what they were going to do and why they were going to do it.

Most of us make these kinds of predictions effortlessly. From planning a perfect date to getting the seating right at a dinner party, we’re able to understand and anticipate each other’s behaviour. This capacity is what philosophers call folk psychology – not the psychology of scientists in labs, but the psychology of everyday life. If I know my co-worker feels undervalued, I know he’ll appreciate an earnest email of thanks, and if I know my friend likes to be seen as an expert on arts and culture, I might make a point of asking her opinion on the latest Tarantino movie. At its most exalted, folk psychology can seem like magic – that moment when the detective intuits exactly what the murderer will to do next, or the lover knows just what to say to make her beloved swoon.

At its core, folk psychology is a matter of constructing models of people – their beliefs, dreams, fears, wants, and needs. In this sense, it’s a matter of storytelling, of creating narratives about the people around us. When we tell a story, we transform a dry and chaotic cosmos of objects, properties, and events into a vivid and tractable world of characters and motivations. And just as a story requires characters, so too do characters require a story.

It’s perhaps tempting to think that these abilities are a rarefied human quality – something required of people navigating complex social environments, but hardly a requirement for an artificial system. When Siri yet again gives me the wrong answer to my query, and I say an exaggerated thank you, it doesn’t matter that she doesn’t recognise my sarcasm. But cognitive scientists have long recognised that our ability to construct and elaborate stories and characters is key to many everyday tasks, from language, coordination, and leadership. And if we want artificial systems that aren’t just crude tools but colleagues, then they’ll need to learn to construct and understand stories – or at least, to convincingly fake it.

II.

In thinking about the importance of storytelling, language itself provides a good demonstration. Consider a sentence like “the scientists gave the monkeys bananas because they were hungry.”

This might seem like a simple bit of text, readily digestible without the need for storytelling or understanding. But there’s more complexity here than meets the eye. Nothing in the rules of the grammar or syntax of English tells you that the ones who were hungry were the monkeys – the word “they” could just as easily refer to the scientists themselves.

The reason we know it’s the monkeys who were hungry is that we’ve constructed a microstory: some scientists are doing an experiment, and they’re making sure the monkeys are properly fed. If we’d been given an unusual backstory – for example, one in which the scientists were only allowed to eat after giving bananas to their experimental animals – then we would naturally interpret the reference of the word “they” quite differently.

Examples like this have created a fertile test for artificial intelligence known as the Winograd Schema. If an AI can satisfactorily resolve this kind of ambiguity, the reasoning goes, it must actually have some intelligence, some ability to understand. Unfortunately, as is often the case in AI research, it turns out it’s easy to cheat on the test. By exposing artificial systems to large corpuses of text, it’s possible to teach them patterns of language and speech which they can use to work out the most likely reference of an ambiguous word. Artificial systems may not be able to understand, but – as it turns out – understanding isn’t necessary in this case for successful prediction.

This kind of ambiguity, though, is just the tip of the iceberg. Philosophers have long recognised that language doesn’t consist of simple atomic propositions, utterances like “the cup is on the table.” Most human language conveys far more than meets the eye: it’s full of shades of nuance and unspoken assumptions that can only be decoded once we have a grip on who we’re speaking to and the purpose of the conversation. This is most obvious when we speak obliquely. If I ask you if Jane is dating anyone, and you pause before replying that she’s been flying to New York a lot recently, I’ll naturally (and effortlessly) recognise that you’re hinting at a distant love affair.

This kind of implicit meaning – what linguists call pragmatics – underpins even simple communication, and involves a dizzying amount of interpretation that we conduct unconsciously. Imagine you’re sitting on a bench in the park and your friend leans over and points in the direction of an ice cream van. You instantly recognise that the person working in the van is your friend’s secret lover. But are they pointing out the ice cream van or their lover?

It depends. If they’ve disclosed their secret lover to you, then it’s reasonable to assume they’re pointing her out. But let’s say you know about their lover secretly – for example, by having read their secret diary without their knowledge. In that case, you know, but they don’t know that you know, so they’d have no reason to expect you to recognise their lover and must be pointing to the ice cream van. But things get yet still more complicated. Imagine that they caught you reading their secret diary. Now they’d know that you knew, and you’d know that they you knew that they knew, so it would make sense they were pointing out their lover (if you know what I mean).

It’s easy to get lost in descriptions of these kinds of complex “mind-reading” scenarios, but none of us have any difficulty in navigating them as they arise. We can keep track of who knows what, and who knows who know what, thanks to our effortless and largely unconscious social minds. It’s interesting and perhaps telling that even our closest relatives, chimpanzees, don’t seem to use pointing gestures in nature, and struggle to understand when scientists use pointing to help them locate food; even in these simple gestures, there’s a rich tapestry of social cognition woven into our everyday communication and even body language.

This casual facility for understanding others is brilliantly demonstrated by flash fiction. When we read a story like Hemingway’s “For sale: baby shoes, never worn”, our minds instantly fill out background details, turning a black and white sketch into a technicolour portrait, something no existing AI would be remotely capable of achieving. In order to understand stories, you have to construct them, by filling out a world with characters, motivations, backgrounds, and personalities.

Of course, not everyone has it so easy. Neurodiverse individuals, and in particular people with autism, often struggle to decode the subtle implications buried in these simple short utterances, and sometimes face real challenges in interpreting indirect communication. I should stress that autism takes many shapes and forms, and many people with autism have managed to find effective strategies for dealing with the frustratingly circuitous communicative tendencies of others. But their experience at the very least shows that the easy social understanding wielded by neurotypical people is a tricky cognitive achievement.

The exact nature of the achievement, however, is still something of a controversy. Do we learn to construct stories about others, or are we born with the ability to do so? Philosophers and psychologists are deeply divided on the issue. One famous experimental paradigm known as the “Sally Anne Test” (or more prosaically, the false belief task) has suggested that there’s a specific window in childhood development – around the age of four or five – when neurotypical children acquire the ability to understand that other people can have their own beliefs and agendas. In the classic version of the test, children see a doll (“Sally”) put a marble in a basket. Sally then leaves the room, and another doll (“Anne”) comes in and moves the marble to a different basket. Sally then re-enters the room, and the children are asked where she’ll initially look – in the basket she put the marble in originally, or the basket that Anne had moved it to?

Somewhat surprisingly, children younger than four seem to adamantly believe that Sally will look in the basket where the marble really is; the idea that she might not know that it’s been moved just doesn’t compute. But around age four, something seems to change for the neurotypical children: they pass the test fairly easily, suggesting they can now make sense of the fact that the world contains people who don’t believe the same things as them. By contrast, children with autism struggle with this test, suggesting that they haven’t yet acquired this ability. And while most adults with autism can pass it, they acquire this ability later, perhaps suggesting that they’ve had to learn to construct stories about others the hard way, rather than relying on some innate ability.

Even as adults, people with autism struggle to pass some subtler tests of this kind. In one such test, for example, participants are told a story about Sarah and Tom who are going on a picnic. Just as they sit down, torrential rain starts pouring down, to which Sarah remarks “How wonderful.” The participants are asked to say what Sarah meant by this. While most neurotypical adults immediately infer that she’s being sarcastic, those with autism are less confident, suggesting, for example, that perhaps Sarah really likes the rain. Here again, it’s the ability to tell accurate stories – to project ourselves inside Sarah’s head, to gauge her likely motivations – that’s key to understanding.

Exactly how to interpret results like these is still hugely controversial among philosophers and psychologists. But the most straightforward reading is that neurotypical people have an innate ability to understand others that “comes online” early in childhood, while people with autism have to acquire this ability the hard way.

It’s not hard to imagine why evolution might have endowed most people with this ability. We’re fundamentally social creatures, and the ability to easily model others’ beliefs and goals – to construct rich stories about each other’s minds – is extremely useful for our thriving and survival. Some thinkers have suggested that this ability is what makes humans so distinctive. For most of our recent evolutionary history, humans have lived in tight-knit social groups in which coordination, cooperation, and reciprocity have been key skills, whether via working together to bring down large prey or just keeping track of our friends and rivals, and stories are what enable us to do this.

There’s also a darker side to our ability to tell these kinds of stories, namely that it lets us manipulate and control each other. If you can effortless intuit other people’s motivations and beliefs, then it becomes easier to control them, whether by feeding them plausible lies or playing on their hopes and fears. And while not every social environment is as cutthroat as Game of Thrones or House of Cards, we’ve all encountered brilliant persuaders and manipulators who always seem to get their way. There’s even a view – the so-called “Machiavellian intelligence hypothesis” – that claims that it was this aspect of our social intelligence rather than cooperation that drove the explosion in our brain size in our recent evolution. Put bluntly, we’re smart because we need to be devious.

While systems such as DeepMind’s ToM-net (short for “Theory of Mind network”) are capable of predicting certain kinds of behaviour – and effectively passing the Sally-Anne test – they lack the understanding required for true manipulation: we need not fear an imminent virtual Iago. And while the cold impersonal intelligence exhibited by the ruthless artificial systems of Terminator or 2001 are certainly dreadful, their wickedness pales in comparison to the Machiavellian hatred of genuinely devious AIs like Harlan Ellison’s famous AM (“Aggressive Manipulator”) of “I Have No Mouth, and I Must Scream”. A system that was blind to the existence of others and their inner lives might be a killer, but it couldn’t be cruel, malicious, or exploitative. If this is right, then we should perhaps be somewhat relieved that this is a kind of intelligence that AIs seem to lack (at least for now). For humans, by contrast, the ability to tell stories is like the forbidden fruit: expelled from the Edenic solipsism of early childhood, we’re faced with a world of actors both malign and benevolent, and become ourselves capable of good and evil.

III.

We construct stories to understand and control. But we also create them to share. From the blind bard of Chios who stitched together the myths of Achilles, Odysseus, and Priam to the Mesopotamian scribes who laid down the tales of Gilgamesh and Enkidu at Uruk, every civilization with a written record has bequeathed to us its folklore and mythology. Exactly why we tell stories – their social and cultural function – is itself a vexed question among evolutionary psychologists, but it’s certainly true that the use of stories not merely as interpersonal tools but as a form of shared culture is that rara avis of anthropology, a near-universal human trait.

It’s tempting to think that our ability to craft and share stories publically is a development of something more basic, namely our ability to construct private mental stories to understand one another. Certainly, it’s hard to imagine that someone could write convincing fiction unless they already had a good grip on how other people tick. When the hashtag #menwritingwomen went viral last year, Twitter delighted in exposing the embarrassing blunders many male authors made when trying to craft believable female characters. Implicit (and sometimes explicit) in the critique was a charge not merely of literary ineptitude or anatomical cluelessness but a certain lack of empathy and understanding for the different experiences of women (apparently women do not routinely look in the mirror and compare their breasts to large items of fruit). It’s natural to think, then, that to tell a story about someone, you first need to get inside their head.

If this is right, then the one career that doesn’t need to fear automation any time soon is that of fiction author. But as proved to be true with linguistic ambiguity and theory of mind, even if artificial systems don’t really understand, they can do a passable job of faking it. A striking demonstration of this came with the development of a system called GPT-2 earlier this year by researchers at OpenAI. GPT-2 is a language model trained on some eight million webpages with a simple goal: predict the next word in a sentence. In this sense, it’s loosely comparable to the predictive text systems we’re all familiar with from smartphones. But GPT-2 goes way beyond their capabilities. Give it a prompt – even a few words – and it’ll wax lyrical, turning a sentence or two into a text resembling a news story, an essay, a short story, or even a poem.

It’s an unsettling experience which is worth experiencing first hand (you can try it yourself online at talktotransformer.com). For example, when I plug in “once upon a time”, GPT-2 returns a nice little poem –

Once upon a time

I was a very strong girl,

But soon I began to fall.

I’ve fallen too far.

But maybe that was too easy. How about a more specific opener; say, “Draco looked at Hermione coldly”?

Draco looked at Hermione coldly.

“I have to keep up appearances in class, you know,” he said. “The whole world gets to know me, that’s part of what makes me so mysterious. But I will keep it quiet if it means we will all be fine.”

“We must all be fine,” she said. “No one is going to want to touch your wand.”

Of course, GPT-2 isn’t operating in a vacuum here: of the 8 million webpages it was trained on, doubtless at least a couple of million of them were Harry Potter fanfiction (many of which probably involved a fair amount of wand-touching). But faced with an AI able to produce passages of fiction that could easily have been written by a real person, it’s hard not to feel human exceptionalism slipping away.

IV.

When we think about humans, stories, and AI, there’s a tension that’s hard to resolve. On the one hand, stories seem critical to our understanding of the world, of language, and of each other. They’re part of what makes us human, and part of the reason our species has been able to thrive so destructively. And yet everywhere we look, we can see artificial systems encroaching on our estates, clumsily but relentlessly doing what we do with stories, all with a complete lack of understanding. For now, most of what we see is a bad cover version: a simulacrum of human behaviour built on very different foundations. But with every new press release from Google or research paper from IBM, it feels like a little bit of human distinctiveness slips away.

When Paul had first told me about Xu Zhimo, I’d been impressed: clearly, anticipating the behaviour of pedestrians in the way he described was impossible for an artificial system that could get inside people’s heads. But the more I thought about it, the less sure I was. If there’s one thing AIs are good at, it’s learning from mistakes. A few chance collisions or near misses outside King’s College would be all it would take for a driverless car to realise that this was a dangerous spot. Given enough time and data, it might even learn to be cautious of large groups of tourists in front of Xu Zhimo’s plaque, and all this without a shred of understanding or empathy.

If AI can do so much without stories, then we face the question of why we tell them at all. Is the understanding they grant more superficial than meets the eye – nothing more than a rose-tinted Instagram filter on reality? Is it a mistake to argue, as I have, that they’re so important for our skills and abilities?

I think not. Even if stories aren’t essential for intelligent beings to understand the world, they’re a cognitive shortcut – an incredible interpretative strategy that lets us pull off miracles of prediction. When someone – even a person we just met – tells us that they’re afraid of flying, or have always dreamed of visiting Paris, or are excited about their new job, we can easily to fill out a picture of them that lets us understand and anticipate their behaviour. When we read a first-hand account of a parent who has lost a child or a soldier left to die on the battlefield, we can gain powerful new insights into human actions and emotions. As far as raw prediction goes, perhaps an AI will one day be able to match us at guessing what a desperate lover will do next, or how a community will react to a sudden tragedy. But it will do so thanks only to having copious amounts of data analysed grindingly over hundreds of millions of processing cycles. We can do it on the cheap.

There’s something almost mystical about this ability. In a memorable passage from Hogfather, the author Terry Pratchett asks us to grind the universe to the finest powder, and find a single atom of justice or molecule of mercy. If we grind the universe to a powder, we won’t find stories, character arcs, or motivations. Yet somehow we can use these things to understand, anticipate, and even manipulate each other. They may not be real in same way as atoms and molecules, but – to borrow a phrase from philosopher Daniel Dennett – they’re real patterns, and we’re exquisitely attuned to them. The stories we tell ourselves aren’t just some Dulcinea we need to believe in for our own comfort; they’re a royal road to understanding.

Henry Shevlin

Dr Henry Shevlin is a philosopher of mind and cognitive science whose research focuses on non-human minds in the form of both animals and artificial intelligence. After spending seven years in New York for his PhD (CUNY Graduate Center, 2016) he is now a researcher at the Leverhulme Centre for the Future of Intelligence at the University of Cambridge, where he leads the Consciousness & Intelligence project.

- Web |

- More Posts(1)