You have no items in your cart. Want to get some nice things?

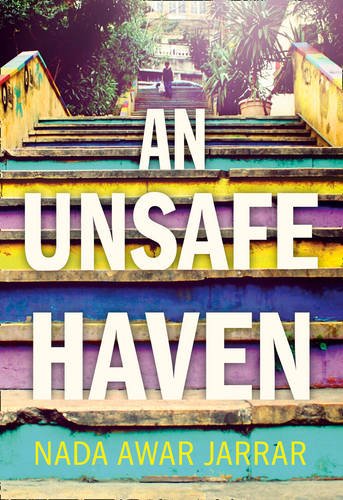

Go shopping Nada Awar Jarrar is a Lebanese novelist who won the Commonwealth Writers’ Prize for her first book Somewhere, Home (2003). Her latest novel, An Unsafe Haven (Borough Press, 2016) is a scaffold of a story inhabited by a few closely knit characters; the reader is subsequently immersed in an appreciation of physical space with the occasional wandering scent of coffee or blossom winding its way through to you from the outset. This successfully sets up an ongoing focus on “place”. The theme of the story is fundamentally one of displacement and identity: a poignant theme recurrent in Jarrar’s writing.

Nada Awar Jarrar is a Lebanese novelist who won the Commonwealth Writers’ Prize for her first book Somewhere, Home (2003). Her latest novel, An Unsafe Haven (Borough Press, 2016) is a scaffold of a story inhabited by a few closely knit characters; the reader is subsequently immersed in an appreciation of physical space with the occasional wandering scent of coffee or blossom winding its way through to you from the outset. This successfully sets up an ongoing focus on “place”. The theme of the story is fundamentally one of displacement and identity: a poignant theme recurrent in Jarrar’s writing.

The story charts the unfurling dynamics within two trans-cultural partnerships and a mother-daughter dyad living in a dry and transitional modern day Beirut. The novel is not afraid to ask major questions. How far can the self can be expressed within coupledom, with all the intimacy and compromise that comes with it? What is the ideal degree of cultural assimilation? This question, in particular, plays out via the western “outsider” characters: a young mother from Berlin and an American doctor. The western perception of “enmeshedness” – stereotypical of the extended eastern family – is juxtaposed with the reality of the locals.

This is, at heart, a political novel, mapping domestic perspectives onto the Arab Spring whose reverberations are still being felt. All around the world, in conflict zones, the silent protest of everyday life grinds on. An Unsafe Haven asks: why? Why stay? Is this a civilian fantasy or an essential political protest? What purpose does it serve, given the surrounding trauma and loss? The importance of the “everyday rhythm of life” is cited in humanities literature as key to trauma recovery and indeed survival. The answers that the novel presents go beyond the demographics of age and gender. They lie in the personal, the everyday minutiae. One of the characters is torn between her children’s safety and her family identity. It’s fight or flight.

The publisher describes Jarrar’s work as part of the “New Wave” of fiction addressing the contemporary refugee crisis. The book projects a refreshing voice into the otherwise formulaic presentation of the plight of refugees by mainstream media. It fractures the myths surrounding the motivations for forced migration. Research suggests that a minority of an affected population leave a conflict area and become “displaced”. The assumption is that it is the strongest – the most culturally privileged (the more affluent and young men) – who have the most resources to enable departure. What is not often talked about is the exertion of free will at the individual level. Yes, many choices are related to the survival – but perhaps “sometimes the price that has to be paid merely to survive is not worth it,” to quote an older character, Nazha, who wishes to return home to Baghdad regardless of the surrounding peril. Are we perhaps bound to choose passionate living over safety? Is integrity of identity more important than just survival? “Father was only half himself when away from Lebanon, not because he had been diminished for want of home but because everything about him that was most true had Lebanon at its anchor.”

Through its realistic narrative, the book does manage to do justice to the meat and bone realities of both conflict and displacement. A unwanted baby serves as the strongest motif of disempowerment, symbolising the particular traumas that women and child refugees may endure. The result grounds this piece of work beyond philosophical indulgence and refocuses the reader onto the reality of, say, the Calais Jungle and our ensuing responsibility.

Unusually, the plight of older people is sensitively considered. Even in regular conditions, the old are concerned about being a burden to others – but in wartime conditions they are amplified. Perhaps old age provides a position in which to reflect on and digest the meaning of one’s preceding life – a process enhanced by remaining immersed in the very places one lived in during that time.

Does one revert to “home” as one approaches the end of life? Certainly, from personal experience: my father, who had lived the majority of his life in the UK and consciously considered it home, was only able to drink Ceylon tea and eat papaya the days before he passed. Is this a physiological reversion or psychological regression? An acceleration back in time through childhood to before birth?

This concern – of how the self relates to place – can be seen as a gentle foray into psychogeography. What are the implications for psychogeography of destruction and grave personal danger? Is what we feel for our homes a kind of love? What determines an authentic connection with place is questioned and its value unpicked. As one character muses, maybe we only get one chance at one point in time of finding home.

As more of the central characters leave Beirut, we are left with a grieving for the place itself: there is a sense of betrayal, an anthropomorphising of the city as being worthy of loyalty. We are invited to question our relationship to place in a more ecological context. What part of me fades when removed from the tapestry of birdsong, earth smell, traffic pattern we have lived in or habituated to? And was it ever a true part of self?

What emerges is a notion of responsibility toward place that is apolitical: more ecological, even developmental.

The carefully chosen title is a beautiful summary capturing the complexity, the strain and ultimately the instinct of how we identify with home, place and belonging. The publishers are certainly right to be proud of this elegant and relevant literary contribution.

About Rushika Wick

Rushika Wick is a poet and doctor based in South London. Her first collection "Afterlife As Trash" was published by Verve in 2021 and highly commended in the Forward prizes. She is an assistant editor for tentacular magazine, a poetry reader for Ambit and editor for sunseekers poetry project. You can follow her on instagram @rushikawick