You have no items in your cart. Want to get some nice things?

Go shopping Last year lots of people I love lost people they love. At times I felt that I was watching an epidemic engineered to oscillate around me unfold. It’s not something I talk about often, because what a privilege to remain untouched personally, to bear only witness, to offer only support. And, with the irrational superstition of secular people, I worry that if I talk about it I might tempt fate to blow her brutal winds a little closer to me, to mine.

Last year lots of people I love lost people they love. At times I felt that I was watching an epidemic engineered to oscillate around me unfold. It’s not something I talk about often, because what a privilege to remain untouched personally, to bear only witness, to offer only support. And, with the irrational superstition of secular people, I worry that if I talk about it I might tempt fate to blow her brutal winds a little closer to me, to mine.

What I have done, with all my near ones grieving all their dear ones is walk around the parks of London. Around and around and around, past heaving Lidos and ice cream vans in the summer, along canals with long boats pumping wood smoke into the washed-out autumn, and treading carefully around dog shit, nos canisters and brave shoots in early thawing spring. Walking in spirals I listened to my best friends talk out the spiralling swirls of their grief.

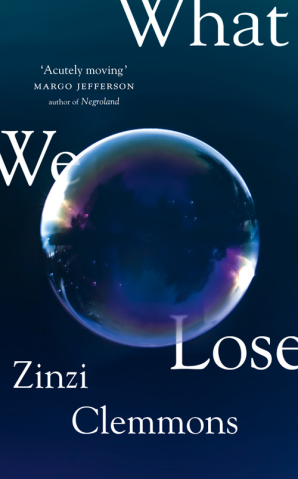

Zinzi Clemmons’ book What We Lose (Fourth Estate) is a book of that swirl, telling one such a spiral. It is a meditation on the loss of a mother and the way the complex life of Thandi, a middle-class black woman in the US, existed before this event and continues after it, growing around this loss the way tree roots do around stones. Grief constructs the form of this novel just as it constructed the walks I took, and so the book circles round and round, back through the birth of children, university, sex, food, the body that Thandi experiences.

In the way that grief picks everything up and shakes it violently so the book sometimes seems to be a litter of disconnected anecdotes and nonfiction interventions. There is an intriguing and profound section two-thirds of the way through about Winnie Mandela and the perception that mothers, including the ‘Mothers of nations’ like Mandela, are nurturing and peaceful. Yet the book presents testimony from the South African Truth and Reconciliation Commission that explores Mandela’s part in kidnappings and murders of so-called ‘informants’. Mothers also do brutal things to protect children of nations, of households. There are many places that Clemmons could have taken this. Perhaps into a discussion of collective grief and restorative justice, especially considering that many South African women still consider Winnie Mandela’s contribution to the struggle equal to – if not more important than – Nelson Mandela’s. Clemmons does not broaden this out, however, choosing instead for it to sit unexplained against a story of personal grief.

This novel is referred to by Clemmons in her acknowledgments as ‘a weird little book’ and indeed it is. But not in a bad way. It is weird in the way that Maggie Nelson and Olivia Laing are weird, in the way that the new nonfiction turn creates interesting books that are deeply personal, the prose incisive, stylised and pared back. Clemmons’ work, while introduced as a novel, reads (at least semi-) autobiographically and it is because of this that I forgave it many messy elements and a few less-than-beautiful sentences than I would a ‘straight’ novel.

Like Maggie Nelson, Clemmons is brave enough to present ideas without explaining everything away to the reader. This is, throughout the book, at times successful and at times less so. The most interesting idea she presents is that emotional and physical states should be braided into an intersectional understanding of who a person is. Intersectionality, developed by Kimberlie Crenshaw and other Black feminists suggests that social categories like race, class and gender are interdependent. Intersectional understanding suggests that the experience of middle-class black women in the United States – which is the experience that Clemmons explores – is a very different to the constellation of ‘woman’ that white women experience and different again to that which working-class black women experience and so on. Clemmons however also suggests that states of feeling, particularly physical and emotional pain, also transform, change, mediate and intersect with social categories usually explored by intersectional work. Just as our gender, race and class (to name but three possible categories) form us differently, so whether we are in pain or not in pain, in grief but not in grief, also mediate the complexities of what it means to be. This book is weird, sure, and certainly imperfect – but Clemmons’ contribution is profound.

About Rosa Campbell

Originally from Sydney, Rosa Valerie Campbell is a 28 year old writer based in London. She has just finished her first novel and is enjoying writing short fiction, poetry, reviews and work for theatre. Her work has appeared in published in Voiceworks, Cellar Door, The Letters Page and others. Her immersive theatre works What I War Today: A play about Primark was put on as part of Futurespark Festival and The Fortress was part of Big Noise Festival. Her poetry is being showcased at Noted Festival in March, 2015. She loves hot strong coffee, her new rucksack and artistic collaborations, so do get in touch.