You have no items in your cart. Want to get some nice things?

Go shopping

On the morning her head exploded, Emily Mason planned her routine as precisely as an algorithm. She woke up at 6:30 a.m. to the buzz of her cell phone and got a glass of mango and orange juice blend from the refrigerator. Then she showered and laid out her work clothes. In addition to the white shirt and navy blue slacks, she selected a black sweater. Mornings had been unseasonably cold and hazy for July because of the forest fires up north. For breakfast, she had toast with Nutella spread and two slices of cantaloupe. Two gentle arcs, not cubes or rhomboids. By 7:30 a.m., she walked down the hill with her roommate Susan Chang to catch the bus to downtown Oakland.

Their apartment was in the Glenview district. There really was a glen beyond the ridge of redwood trees. A creek ran along the glen and there were supposed to be rainbow trout in the clear cool pools. Emily had never seen them even though she stopped and looked each time she hiked along the creek. If you looked at just the right angle between the craftsman bungalows, there was a view of the Bay Bridge and the San Francisco skyline. Familiar dogs and their owners greeted Emily and Susan from both sides of the street. A pug danced at the end of its leash and a chocolate Labrador cocked its head in greeting.

A cool breeze coursed through Emily’s hair as they hurried towards the bus stop. Then, as sudden and overwhelming as a thunderclap, she felt a burst of pain behind her eyes. Behind her ear drums, she heard a load roar like waves crashing on a rocky shore. She fell sideways, hitting her left shoulder and hip on the pavement but that pain was miniscule compared to the headache. As she lost consciousness, she saw Susan hunched over her and then the light dimmed as if Emily had been on stage and the show was now over. Am I dying? Emily thought. She saw strange wavering permutations of the clouds and then there was nothing, as if all the bright colours of her world were smeared grey with a broad palette knife.

Susan called 911 and then Emily’s mother who said would said she would take the next available flight from Los Angeles. The paramedics arrived within ten minutes and transported Emily to the downtown emergency room. Immediately after the CT scan, the emergency room physician called the neurosurgical service in San Francisco to arrange for transfer. Emily’s diagnosis would require specialized care only available at a tertiary centre.

As she drifted in and out of consciousness, Emily became aware of a continuous stream of nurses and physicians checking on her. Emily looked up and saw the green and blue tracing on the wall monitors. There was the regular rise and drop of her electrocardiogram and the steady repetition of the trifid wave form of her intracranial pressure measurements. A young nurse came to measure the pink fluid in the drip chamber that connected to the thin plastic tube exiting the front of Emily’s skull.

“How does it look?” asked Emily’s mother. She sat on a side chair and placed her right hand over Emily’s forearm. Like Emily, she had pretty green and gold hazel eyes but her eye lids were puffy and she looked like she might burst out crying at any moment.

“The blood is clearing and I see that Emily is waking up,” Marissa said with a bright smile. She wore powder blue scrubs and white tennis shoes. “She may be ready for surgery soon.”

Marissa asked Emily to measure her pain on a scale from zero to ten, before and after the Morphine. She asked each question with a cheerful expression and patient tone. Some people were just like that by nature, Emily surmised. From her back pocket, Marissa pulled out a diagram that had a series of line drawings of faces with increasingly painful expressions. If she had been asked on the Glenview side walk, Emily would have said off the scale, one hundred. Emily scrutinized the row of circles with dots for eyes and curves for smiles or frowns. Zero was a smiley face and ten was a crying face. The past few hours had been marked by alternating headache and then almost euphoria as the Morphine took effect. She picked seven for before the Morphine and four for right after the infusion.

*

On Monday morning rounds, Dr. Gabriel Reed, a surgical intern on the neurosurgical service, reviewed the surgery that was planned for the next morning. He wore a light blue shirt and navy blue slacks underneath his short white coat.

He looks no older than me.

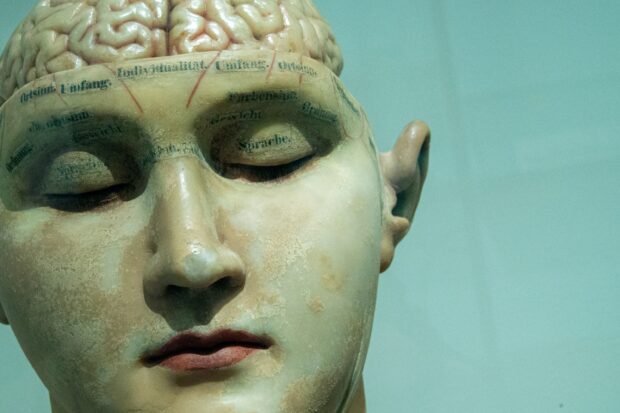

Reed explained that Emily had an aneurysm, an abnormal out pouching of a major artery in her brain. When the aneurysm ruptured, the blood blocked the pathways for cerebrospinal fluid and the brain ventricles ballooned. When Emily had been admitted to the intensive care unit, Dr. Mathew Trujillo, the chief resident, placed the brain catheter through a twist drill burr hole in Emily’s skull. Two days passed until Emily’s speech became understandable. She was in good enough condition now to undergo the major surgery to clip the aneurysm.

“Will you be there?” Emily asked.

“I will assist,” Reed said. “Dr. Trujillo and Dr. Narayan will be the main surgeons.”

I’m an unusual case that requires both the chief resident and the senior neurosurgeon.

She was rara avis, a hyacinth macaw or a blue bird-of-paradise flying above a flock of grey pigeons. She was not another stumbling wino who hit his head on the sidewalk.

*

Dr. Trujillo saw her midday, between surgical cases. He looked like a grown up boy genius with a thick helmet of unruly white streaked hair.

How many thousands of examinations has he taken? Likely thousands and aced each one.

On the computer screen at the bedside work station, Trujillo showed Emily her angiogram. Emily stared at the images. The base of the skull was a series of ridges and crevices through which blood vessels splayed out in a radiating branching network. They look like a spider web. Emily imagined the aneurysm as a black spider hidden in the darkest crevice, waiting to lure her prey and wrap them in her sticky spittle.

“Will you have to go through my brain to get to the aneurysm?” Emily asked.

“We will go between the frontal and temporal lobes,” Trujillo explained. “We won’t damage brain tissue.”

*

Dr. Narayan arrived on Monday evening. The neurosurgical team stood outside her room and reviewed her case. Narayan wore a grey pin striped suit with a crisp white shirt and a blue and gold stripped tie. Likely his college colours.

“Tomorrow is the big day,” he stated. “Your condition is now optimal for clipping.”

“Are you sure you can clip the aneurysm?” Emily asked.

“Yes,” Narayan said. “We have never failed before.”

“Could I have a stroke during surgery?” Emily asked.

“There can be unexpected complications,” Narayan continued. “But we have prepared for all the possibilities. The most important thing you can do now is to get a good night of rest before surgery.” Narayan gave her a confident smile and nod and then the team followed him to the next room.

*

As she watched the green and blue tracings on the electronic monitor, Emily tried to picture the blood clot deep in the left side of her brain. The clot was all that kept the aneurysm from bursting again. All the vital signs were stable for now but could change at any second. For an instant, Emily felt a cold panic but then she took a deep slow breath and resolved to endure what was unavoidable.

Emily took stock of her predicament. Before her head exploded, her worst experiences had included breaking up with her boyfriend after high school and almost failing calculus class during freshman year of college. Death had not approached her circle of family and friends. A classmate in high school overdosed on heroin but he was not a friend. The veterinarian put their cat down when Rex developed kidney disease. But now, a bloody time bomb had detonated in her head and could explode again tonight or during surgery.

Emily’s mother started to arrange items on the side table. First, the toiletries and then, the newspaper. She placed the cell phone, a hairbrush, and a wash towel in a neat row. She rolled the towel but then changed her mind and folded it twice to make a tight square

“You don’t need to do that,“ Emily said. “I might not be in the same room tomorrow.”

“I know. It’s just a distraction

“Just sit beside me,” Emily said.

They looked across bay and as the lights come on along the bridge cables. As evening progressed to night, images of her past appeared to Emily as if projected on the window. She saw the youthful face of her mother as she dressed Emily when she was a young child. She smelt granola and then chocolate cake baking in the oven. She told her mother that she remembered a vacation to Carmel when she was six years old. Her mother and father were holding each of her hands. The sand was wet and warm. They lifted her above the splashing foam and her laughter fluttered like a wind chime in the summer breeze and across the cerulean water. Her mother said that was one of her favourite memories as well.

She thought of Rex, their tabby cat. In the evenings after school, he waited for her in the foyer. She stroked his belly when he rolled over. She held him on her lap while she studied and he would lick her fingers. While she was at school, Rex spent most of his day lounging next to a heating vent. Emily could tell where he crept by the shed hairs on the living room couch or the dining chairs. Hummingbirds taunted him at the windows. Dogs lunged at him from the sidewalk. When Emily came back from the first semester of college, Rex hissed at her as if he resented her for growing up. Rex taught me how to love but not presume love returned.

She ruminated about Paul, her high school boyfriend. They knew each other since grade school and started dating junior year. He had been too eager to get married and get on with life. Paul did not even try for university and entered his father’s contracting business right out of high school. She heard that Paul now owned a water front condominium but was not married. Maybe I made a mistake.

Marissa returned to check on Emily. “Is there anything I can do for you?” she asked, still calm and cheerful near the end of her shift.

Please make time reverse to before my head exploded with a thunderclap. Make sure the surgeon is steady with the clip.

“Has everyone you have seen with my diagnosis done well after surgery?” Emily asked.

“You are young, healthy, and in good neurological condition. You should do quite well.” Marissa checked for blood clots or air bubbles in the tubing connected to Emily’s brain catheter.

“Has anyone with my diagnosis died?” Do I really want the answer? Her mother pursed her lips.

“Only an elderly patient who was in coma to begin with. I would not worry about that.“

“It’s hard not to worry,” Emily’s mother added.

“Try not to worry about what’s out of your control,” Marissa said. “Trust that you are in good hands.”

“I do trust them,” Emily said. Everything did come down to that. Her surgeons studied and practiced for years and would not falter now.

Marissa gave Emily’s hand a gentle squeeze and continued on her evening rounds.

As Emily gazed out the countless city lights, she understood that tomorrow would be the most important day of her young life. She knew that disease and death caught up to everyone. Her grandparents might die within a few years and her parents within in a few decades. With a shiver, she understood her time really could be now.

What will I miss?

Emily recalled the pile of unread books on her night stand at home. She wanted to read all the novels of Jane Austen and Gabriel Garcia Marquez. She wanted to study Italian and visit Venice before the sea reclaimed that unlikely city. She wanted to see the Aurora Borealis from a remote Alaskan wilderness and snorkel in the coral gardens of the Bora Bora lagoon. If she had children, she wondered how she would tell them her story.

What parts will I highlight and what parts will I leave out?

Emily resolved that if her surgery went well, she would repay her gratitude in ever widening circles. She closed her eyes, took a deep slow breath, and braced to endure whatever tomorrow brought.