You have no items in your cart. Want to get some nice things?

Go shoppingThe development of computer technology is to a great degree driven by the development of computer games, and to a large extent that development is used to power the graphics, the visual part of a game. The human brain uses most of its energy to process visual information, and in a similar way will much of a computer’s power go to display the graphics, everything we see in the game.

Yet for all their visual power, games and the computer technology behind them have problems presenting truly lifelike and detailed human or animal characters. Few would confuse a computer generated image of a human being with a photograph of one. But as opposed to human characters, there exists no such “uncanny valley” between the architecture presented in a game and its player. It is perhaps not strange, then, that architecture has many functions in games, perhaps even more than it does in our everyday lives.

Architecture as the Real, the Past, and the Future

The most obvious function for architecture in games is as backdrop and props for the game’s narrative and characters. By mimicking familiar landmarks and buildings, architecture establishes a time and a place for the game, as well as affording it a claim to realism.

The famous and infamous Grand Theft Auto games are examples of this. They mimic (with a few sly changes) not only the architecture and buildings of cities such as New York, Los Angeles and Miami, but also music and clothing typical of the place and time in which the game is set.

By subtly, or not so subtly, changing famous cityscapes and architectural landmarks, games can present alternate versions of the past, or possible futures, such as Bioshock Infinite‘s Americana-style dystopia, the steampunked London in Thief, and the near-future Chicago of the upcoming game Watch_Dogs, where the player hacks into the city’s computer controlled functions, such as electricity and surveillance cameras, for their own ends.

https://youtu.be/bmwyW-Q960M

But unlike the architecture in everyday life, architecture in games does not need to concern itself with building costs, practicality, scale, or even gravity. Thus, games from the classical Myst series to the ongoing Final Fantasy role-playing games present architecture that is effortlessly impossible; gigantic flying fortresses, spires that stretch kilometres into the air, or castles built on the edges of waterfalls.

Perhaps in the games of the future the architecture will look more detailed and “real” than that of our own world, or be able to recreate the past to a detail and degree of immersion no museum display can do. Videos of the upcoming game Assassin’s Creed: Unity presents a 1:1 scale version of Paris during and after the French revolution, with an architecture that is extremely researched and detailed.

Architecture as Gameplay

Even though the architecture in games consists of weightless pixels, its second and perhaps most important function is to provide barriers where they are needed, and drops or ledges where those are necessary.

Since the earliest platform games (Donkey Kong, Mario Bros., etc.) architecture has been an intrinsic part of the gameplay which the player must learn and master in order to progress. In games, players must navigate hallways and corridors so large and labyrinthine that even Theseus would have hesitated to enter (Doom, Unreal, Half-Life), perform gravity-defying, vertigo-inducing leaps across platforms and ledges (Portal, Prince of Persia), or scale the outside of tall buildings (Mirror’s Edge, Assassin’s Creed), all while being chased by opponents controlled by the game. In games where fighting is not really an option, the architecture and learning how to navigate it becomes even more important, such as the poetic game Journey, the empathetic Ico, and the frightening Outlast.

Yet, the architecture in games is not only a problem that must be solved, an obstacle to overcome, or a challenge to be met. In stealth games such as the Splinter Cell series and the Metal Gear series, the architecture is the player’s weapon with which to confuse, trap, or evade enemies by luring them behind corners, attack from pipes in the ceiling, or slip quietly away through ventilation shafts.

https://youtu.be/VSAD6LktJGo

As the player becomes more and more adept at the gameplay and at navigating the architecture, it will progressively increase in complexity and difficulty in order to challenge the player and maintain her interest.

In massively online multiplayer games (MMO) – of which World of Warcraft, with its more than 10 million players, is the biggest and most well known – a large part of the game’s activities take place inside structures called dungeons. These are enormous locales that can accommodate groups of up to twenty-five players, in fierce battles against groups of computer-controlled enemies in what is considered the most challenging gameplay of the genre. Usually, these group battles require the players to read and coordinate their use of the architecture correctly, from clicking on doors, to herding the enemies into parts of the structures where they will be easier to fight.

Thus, in games, architecture isn’t simply buildings or houses, but to a large extent how the game communicates with the player and imparts its tasks to them. It is no wonder that one academic commentator on games concludes that “the narrative in games is not primarily reliant on story, nor on character, nor on language. Rather, the primary narrative mode of games, is spatial. Spatial stories and environmental storytelling provide a staging ground where narrative events are enacted” (Janice Lee).

Architecture as Narrative

Since a game’s narrative isn’t expressed only by the game’s characters and their actions, but via the environment of the game and what the player does there, architecture is especially significant for games.

In our everyday life, all human-made objects have been designed, constructed, and produced by someone. But in games, not only are all human-made objects created by someone, but so is everything else the player can see on the screen, even natural processes such as decay, weather, or light conditions. The trash in the street, the cracks in the pavement, the mud on the vehicles, everything is there for a reason.

Often that reason is to create a certain atmosphere or to induce specific emotions in the player. In many games, especially those with a dark or tense plot, the characters’ inner state and that which the game wishes to impart on the player is visualized by architecture and landscape.

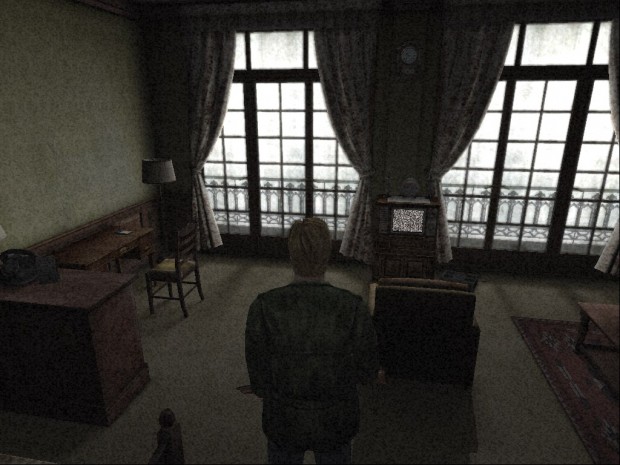

In the classical horror game Silent Hill 2, the plot first removes the player from her ordinary world by taking her down a long and winding path in a fog-filled forest which it takes minutes in real-time to traverse. This is long enough for the game’s sense of isolation and gloom to really sink in. From there the player must find her way through various locales that devolve from the homely and familiar to the unsettling and monstrous.

Thus, like a digital Orpheus, the game’s protagonist must search the underworld, first in his notions of home and safety (an apartment building), then among memories consciously kept and treasured (a museum), to the sense of being trapped in an untenable situation (a jail), to admitting old traumas (a hospital), before he can finally accept life as a fleeting, momentary state (a hotel), and escape.

Architecture as Player Housing

For some games, presenting the players with an architecture full of challenges and narrative is not enough. Several online multiplayer games provide small pieces of architecture to its players: houses, spaceships, or whichever unit of domicile is appropriate for the game world. The players buy or obtain this player housing from the game in other ways, and place their virtual homes in designated areas.

Along with housing, these games also provide ways for the players to purchase or create a great variety of furniture, pets, servants, crafting stations, or other items to decorate their housing with. In these player-“built” spaces, players can meet, talk, fight, party, and just about everything they do in their real life homes.

On a larger scale, members of the game’s player organizations, called guilds, can pool their resources and buy and furnish a large housing space, a guild hall. Online games offer this to make players invest more time, energy, and real life money in the game. Player housing can become one of the most popular aspects of a game, as it was for the science fiction MMO Star Wars Galaxies, and may become for the upcoming fantasy MMO EverQuest Next.

In yet other online games your home can literally be your castle. Some MMOs, such as The Elder Scrolls Online and Age of Conan, offer guilds the opportunity to build castles or fortresses in areas set aside for that purpose. Opposing guilds or players can then purchase or build engines, siege the fortress, and engage in large-scale battles involving 48 players or more on each side. Such guild fortresses and siege battles are another selling point of certain MMOs, particularly those who focus on player-versus-player fighting.

Breaking the Boundaries

Yet, despite all the vital functions architecture has in a game, we can not talk about architecture without also mentioning how players always explore the boundaries set by the architecture and try to move beyond it. Players do this out of curiosity, the sheer thrill of it, and to find out if it can give them some kind of gameplay advantage.

Hence, they will scale walls thought to be impassable from the game designers’ side, climb up on rooftops or mountain peaks, swim for hours to the edge of the map, or spend weeks finding the fastest and most efficient way through a building.

Game developers are well aware of this behavior and usually set barriers to prevent players from falling off the edge of the game world or entering the buildings that serve as backdrop on the horizon. The developers of Grand Theft Auto V even placed a poster on top of their version of the Golden Gate Bridge. This poster says “There are no Easter Eggs up here. Go away”. In MMOs, putting yourself in a place where you can reach opponents but they cannot reach you, may be enough to be banned from the game.

Conclusion

Clearly, in games, architecture is much more than backdrop or set pieces, but serves as mediator for time and place, gameplay, narrative, atmosphere, characterization, customization, and limitation, or all of the above at the same time.

This may be one of the aspects of games that sets them apart from other media and makes at least one academic researcher of the field conclude that “Games are not part of the narrative media ecology formed by movies, novels, and theatre and should perhaps not be compared with it”.

The games for the next generation of consoles were presented at the big games conference E3 this week. Many of the games showed a stunning level of detail of architecture and landscapes that was close to photo-realism. One game, The Division, even introduced its narrative of a pandemic disaster through the architecture and decay of a city apartment.

Perhaps this continued development and refinement of the architecture we see in games will also mean more complex narratives and characterizations, as well as challenging gameplay? Who knows what virtual architectures will arise in the games in the future and how they may influence us as players and human beings.

About Berit Ellingsen

Berit Ellingsen is a Korean-Norwegian writer whose stories have or will appear in W.W. Norton's Flash Fiction International Anthology, SmokeLong Quarterly, Unstuck, and other places. Berit's short story collection, Beneath the Liquid Skin, was published by firthFORTH Books in 2012, and the novel, Une Ville Vide, by PublieMonde in 2013. Berit's work has been nominated for the Pushcart Prize, the British Science Fiction Award, and included in the Wigleaf top 50 longlist. Find out more at https://beritellingsen.com.