You have no items in your cart. Want to get some nice things?

Go shopping

You were not lying on lounge chairs next to an abandoned pool in a cheap New Jersey motel waiting for the sun to come up behind Manhattan’s silhouette. No, you were not naked and you didn’t fall asleep in her arms first and it wasn’t as if it were true that all living beings rise at the same time, as if it were true that you and her needed the sun to tell you that it was time, it was time to unravel your bodies like ribbons to witness the sunrise she had brought you there to see.

No, that was not you.

—

I was not living in a co-op building in Sunset Park, Brooklyn. I was not subletting a one-bedroom apartment from an anorexic painter named Marcie. The bedroom’s walls were not stenciled with yellow Rorschach pelvises; the kitchen wall’s cornices were not glazed with scarlet, nor were there sky blue columns on each side of the living room. I was not rearranging the chunky couches and sundried lamps for the last time, or dusting the black and white photographs of polka-dotted Great Danes for the last time, at the same and only time he said, “you are a bad person.” I had not only lived there for five months before I fucked you and left him.

No, that was not me.

—

In our Mission things were heavy

The smell of new tiles

Mac and Cheese, please

The greenness of all times and spaces and trees

—

I remember, though.

I remember us walking towards Russia.

“RUSSIA,” you said, the vodka rolls down the S’s, what a name, no one could ever come up with another one like it.

The flowers growing on Russia’s trees opened their legs towards us, grass broke through Russia’s sidewalks so we could play with its green hair and a little girl drew pink, blue and red chalk balloons on the exteriors of houses lining up the hill.

I fell with my arms open like a ballerina at the top of the cement garden. Cars drove by playing rap music. You wore your hair in Afro curls. Your sweater felt like a bindle filled with rocks. You wore one of its sleeves and let the other one hang and eventually took it off and wore it over your shoulders.

“Let me carry it,” I said.

“I can’t take any more changes,” you said.

I saw moths and scorpions underneath my eyelids every time the tip of your tongue swept the insides of my mouth. A butterfly’s mouth grabbed ahold of mine. The pores on your cheeks and chin watered the scars of my old pimples with sweat, my palms hurt from touching your skin so much and so long our skins were all the same. One moment you wore Afro curls; the other you wore an Icelandic crown on top of your shiny elfin ears slathered with white glitter.

“You have beautiful ears,” I said.

“Ears are important,” you said.

Your ears had always seemed small. I must have never looked close enough because your ears are the most perfectly shaped and sized part of your body. I traced the birthmarks of your ears down your milky nape round the lunars of your chest and sketched the constellations of the Milky Way.

Our eyes fell moistened by what we saw in each other, had not seen before and still could not see. I had never loved you more nor so strongly seen that part of me that does not love anything or anyone at all.

A sticky cloud of mucus crystalized in my stomach.

“I feel you’re weak,” I said.

“I know,” you said.

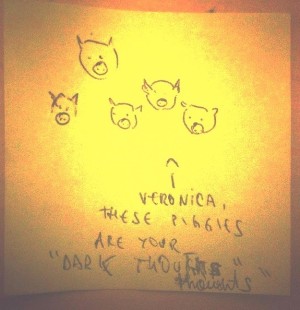

“Say hi,” you said, “Say hello to your dark thoughts.”

“Hello,” I said, and you drew five cute little pigs inside my viscous cloud.

“Ask them how they are,” you said.

I addressed them one by one:

How are you?

How are you?

How are you?

Who are you?

What are you?

We fell on the cement sidewalk on the corner of Russia and Brazil.

Reason was superficial, our feelings placeholders for places that do not exist.

The stomach was and is always inside. Our differences materialized in droplets, tears—our insides exposed so that we could uncover ourselves backwards and wear ourselves inside out like a snake that sloughs all of its parts including its eye caps.

I took your shirt off even though the curve of your back and your head hanging low told me no. I began to cry because I felt I was ripping your skin off instead of letting you shed. You were shedding slowly. I say slowly only because your clothes were coming off more slowly than mine. I had left all of my clothes on that cement hill where I fell. And all I had left were the dead cells born in my head hanging in purgatory down my back. I struggled to untether my body from their split-ended strands. The trail of death is sticky slug slime.

You watched me as I tried to pick off my deadness. You said I looked like an abandoned bear cub and I wept for you to lick off the leftover placenta on my fur. I wept for you to bring back the clothes I had abandoned on that hill; I wept for you to dress me, I wept for you to undress yourself.

You told me that somewhere a room exists with walls covered in shelves displaying the eyeglasses of everyone you have ever met. Every pair of eyeglasses has a tag with a name on it: Mami, Papi, Vanny, Abuela, Michael, Andres, Alejandra, Cristina, Nora, John, Sydnie, Nicholas, Craig, Sophia, Ben, Chris, Rachel, Vanessa, Claudette, Alex, etc.…You told me to visit the room, pick a pair of glasses off the shelf and clean the lenses with soap and water before witnessing what the world, its colors, its things, and its people looks like through someone else’s eyes. You told me you had visited the room to clean the lenses of my glasses so you could see life through me. When you put my glasses on you saw the world exactly as you always did.

There was no difference.

Your nose began to bleed and you asked if I had ever tasted blood before. I said I had only tasted my own so I stuck my tongue up your nostril. And although at first your blood tasted like iron and mercury, then it was life I could not stop consuming. I bit your nose to live through you and because of you at the same time; I judged you through me and because of you at the same time.

I say you are messy.

I say you are not as good at cooking as me.

I say you do not like dancing as much as me.

I say you are careless with money like me.

I say you like music with no soul.

I say you are shy in public.

I say you make hasty decisions.

I say go.

I grow another belly.

I see you are my best friend.

I see you make the best omelets.

I see you draw cartoons of us with hearts on lined paper.

I see you collecting spare change.

I see you laughing with your friends.

I see you stringing stories.

Pig #1 judges you like it once judged me.

Pig #2 takes and does not give back.

Pig #3 pretends to be everything I could ever want.

Pig #4 claims everything is your fault.

Pig#5 appears to be something it’s not.

Icelandic princess with Afro curls and glittered elfin ears, you are electronic, I am guitar djembe, and we are love, free in the better worse and in the same difference. Because of you, I see the feet of my gut-feelings skipping over never-ending nerve endings; I see movement inside of the brick and straw walls of my body where pigs may fade or multiply in all kinds of water. I put my hand in your pocket and find my glasses, I see we will carry our own and each other’s glasses everywhere we go.

I see.

I see you levelling out the acid in my spine.

I see we close our eyes at the same time to the beat of this song.

I see you spitting saliva on my eyeballs and wiping them squeaky clean.

I see our reality repeatedly correcting itself.

—

Today we can’t talk about yet. The coming and going from each other is too frequent. Our age impatient, our eyes always tired. We’re realizing no drug may be strong or multifaceted enough to ease our quickly evolving pains. Today we can’t talk about yet, but we do eat waffles and take photos of our penguin coffee mugs sitting across from each other on a booth at Eddie’s Dinner. Often you fall asleep with your glasses on and I take them off. Often I wear my outdated glasses that give me headaches. You say I should go to the doctor, I say I know and still don’t go. Today when you woke you asked, “glasses?” Sometimes I don’t know where they are but find them before you. Today I mistook mine for yours, “these aren’t mine,” you said and put them on anyways. Your eyes squinted as you leaned closer to my face to remove a piece of dry skin from my nose.

About Verónica Jordán-Sardi

Originally from Cali, Colombia, Verónica Jordán-Sardi immigrated to the United States with her immediate family as a young teen fleeing sociopolitical unrest. She holds a B.A. in English Literature and French from the University of Florida an M.A. in Comparative Literature from the University of Iowa and an M.F.A. in Creative Writing from California College of the Arts. Her work can be found in the Columbia Journal and the Comparative Literature Commons. Verónica currently lives and writes in San Francisco, California.