You have no items in your cart. Want to get some nice things?

Go shopping

Last week’s unveiling of the Man Booker Prize longlist, the first since chairman Jonathan Taylor’s September 2013 pronouncement, “We are embracing the freedom of English… wherever it may be. We are abandoning the constraints of geography and national boundaries”, elicited the usual roundup of author omissions in the press. Almost uniformly, the media listed some combination of Ian McEwan, Donna Tartt, Will Self, Martin Amis, Sarah Waters, Nicola Barker and Philip Hensher as those Irish and Commonwealth authors particularly disadvantaged by the new, global, Booker scheme. Some reports highlighted its lack of women, three out of thirteen, and others noted that roughly a third was American — which, depending on your books editor, either confirmed or finally struck down the idea that the Booker had discreetly swapped its Kingfisher for a Coors Light.

Most striking, however, was the fact that British-Indian Neel Mukherjee represented the sole non-white novelist in this new phase of avowed globalism. Compared to the 2013 longlist, which included Tash Aw, NoViolet Bulawayo and Jhumpa Lahiri, this year’s crop signals a disappointing retreat, even as the Booker Foundation insists that its mandate is now set in international diversity. That its committee was largely unable to identify — from a global pool —worthy novels whose authors were not white men is a baffling result that borders on debacle. Such titles as Kamila Shamsie’s A God in Every Stone, a delicately crafted story examining the relationships between cultures and histories, Hanya Yanagihara’s The People in the Trees, a confrontational novel tackling power and innocence, or Xiaolu Guo’s I Am China, a layered and multivoiced narrative spanning continents, would sit comfortably beside any of the books under consideration for the 2014 award.

Jury chairman A.C. Grayling’s hollow assurances that the committee’s selections were based on literary merit, irrespective of gender and nationality, have done little to assuage these concerns. As bloggers and columnists have observed, his panel absurdly managed only one more woman, and one fewer person of colour, than men named David. Electing four British academics and two ex-pat Americans living in England to select six Britons, four Americans, two Irishmen and an Australian is perhaps not the best way to reinforce a newfound commitment to “the freedom of English” across the globe. If, as the Booker Foundation pledged in its grand autumn press release, 2014 marked a renewed dedication to international Anglophone literature, it would have been advisable to ensure that this generous spirit of egalitarianism was reflected in practice.

Tempting as it is to be swept along this current of outrage, it’s worth remembering that the Booker Prize remains an establishment publishing event that brokers hotly tipped business properties and should not be mistaken for a meaningful barometer of literary worthiness. The prize has in the past played a key role in propelling howling mediocrities into the commercial stratosphere. Complaints on representation and the absence of smaller or experimental publishing houses are annual sport for literary commentators and water-cooler fodder for industry insiders.

The award’s significance to the reading public, however, lies in the popularity of its brand. Even those authors omitted from the shortlist will surely highlight their longlist nod on blurbs and press kits. A Booker nomination is an important statement on a writer’s critical and popular appeal — alarmingly, most of the English-speaking world has appears to have been found lacking. Though the chosen novelists are deserving, the 2014 cohort represents an utter failure of imagination and mission on behalf of the judging committee. Offered an opportunity to make a decisive mark on the selection process following their organization’s noisy proclamation on its global outlook, the judges instead opted to punt.

The Booker Foundation’s understanding of “global expansion”, as they call it, is a curious thing — this turn of the nomination wheel yields only four of the 58 nations where English is an official language, not counting the many, many, other countries where it is spoken. As it stands, this year’s badly miscalculated selection only seems to reiterate the borders Man Booker moved to erase less than ten months ago. To tap into the alleged American flavour of Booker 2014 and paraphrase the tortured war cry of long dead Brooklyn Dodgers fans, maybe next year.

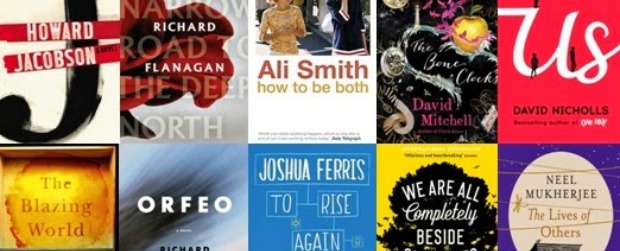

If you haven’t already seen the Man Booker Prize 2014 longlist, here it is:

To Rise Again at a Decent Hour, Joshua Ferris (Viking)

The Narrow Road to the Deep North, Richard Flanagan (Chatto & Windus)

We Are All Completely Beside Ourselves, Karen Joy Fowler (Serpent’s Tail)

The Blazing World, Siri Hustvedt (Sceptre)

J, Howard Jacobson (Jonathan Cape)

The Wake, Paul Kingsnorth (Unbound)

The Bone Clocks, David Mitchell (Sceptre)

The Lives of Others, Neel Mukherjee (Chatto & Windus)

Us, David Nicholls (Hodder & Stoughton)

The Dog, Joseph O’Neill (Fourth Estate)

Orfeo, Richard Powers (Atlantic Books)

How to be Both, Ali Smith (Hamish Hamilton)

History of the Rain, Niall Williams (Bloomsbury)

Litro’s mission is to find the best and most exciting new voices in fiction and non-fiction and give them a platform for their work. To read work from other writers to watch, get our All-Access membership for subscription to our print magazine, membership of our Book Club and unlimited online access.

You have a point, and I say that even as a man named David. Question is, which annual prize should we pay attention to instead?