You have no items in your cart. Want to get some nice things?

Go shopping

Sometimes, someone has to point out the obvious.

Like when Leslie Fiedler analysed classic American literature in his book, Love and Death in the American Novel.

He didn’t actually (as many believe) accuse the great American writers of the nineteenth century of being closet homosexuals, but he did point out (rather amusingly, it seems to me) that many of the great works of fiction from the new continent (Moby Dick, the Leatherstocking novels of Fenimore Cooper, and Huckleberry Finn, to give just a few examples) featured plots that were perhaps not quite ‘adult’ in an odd way, and of course, all paired a white male protagonist with an almost umbilically linked black male companion. (Ishmael and Queequeg, Hawkeye and Uncas, Tom Sawyer and Huckleberry Finn).

It was obvious, but no one, up to the point when Fiedler came on the scene, had had the nerve to point it out, even if they’d seen it. Legend has it that Fiedler was approached by Hemingway at a party. “D- do you really believe all that about Huck Finn?’ he stammeringly asked. (Fiedler’s book was the development of an earlier essay he had written, more challengingly titled ‘C’mon back to the raft, Huck honey’.) Whether or not the story is true, Fiedler’s observations scandalised the critical establishment of the time. Some would argue that they haven’t quite got over it to this day.

Not that his observations make the books any less impressive or important. Fiedler’s theory was that America, with its Puritan tradition, had a different psychological framework to that of Europe, where a vigorous Catholic tradition allowed for confession and forgiveness. Americans specialised in repressed guilt.

The plots of these novels though are more reminiscent of young adult literature. Their basis is in straightforward adventure, rather than the more adult (social) themes of the (decadent?) old world. But is that a bad thing? I remember someone pointing out to me once how ‘adolescent’ Keats’ poetry was, but surely that is the whole point about it? It captures the vigour and passions of youth in a way that other, more mature, poets can only gesture at. But that, as they say, is another debate completely.

Thinking about those American novels though, made me ask whether there aren’t novels of value that might approach the same levels of importance in the British tradition, and whether because of the ‘immaturity’ of their subject matter, they might be undervalued. Do such things exist, and do they, even if perhaps less substantial than say, Great Expectations, sit alongside in terms of sheer quality?

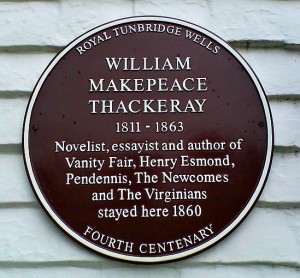

Leaving aside for a moment the fact that the wonderful Thackeray, who belongs perhaps more in a European tradition than a British one, is consistently overlooked, largely because his genius in confronting chaos may be slightly too foreign for British taste. At the point where Dickens resorts to comedy and satire or some mawkish pathos – look no further than David Copperfield’s relationships with Dora and Agnes – Thackeray gives us sexual behaviour in social contexts even more complex than Madame Bovary or Therese Raquin, particularly in Barry Lyndon, his masterpiece (which translated brilliantly into Kubrick’s film), and Vanity Fair, which runs it a close second.

But I’d like to propose the reinstatement of a couple of works of imagination that hardly seem to feature (except perhaps as symptoms of the age) in the critical canon. I’m thinking of Robert Louis Stevenson’s Kidnapped and Rudyard Kipling’s Kim.

Both are rites of passage novels. The hero comes to knowledge of himself and his world through dangerous exploits in unhospitable circumstances.

David Balfour, the 17 year old hero of Kidnapped, has delusions of grandeur. On his father’s death, he goes out (with much the same attitude perhaps as Laurie Lee, walking off to Spain on that summer morning) to reclaim his inheritance. His dead father’s brother, a psychotic miser of breathtaking proportions, tries to kill him – by beguiling David into going up a staircase of a ruined tower in the dark to bring back documents; only a bolt of lightning prevents David from stepping off the staircase into a fatal void.

That one scene, so dramatically rendered it seemed to me then, in the BBC’s Sunday Serial production, had me trembling for most of the week.

But even this somehow gets smoothed over, and David is once more taken in, allowing his Uncle to have him kidnapped by the sea captain, Hoseason, to be taken to the Carolinas in servitude. Enter then, by the most improbable deus ex machina circumstance (Hoseason’s brig runs down a boat in the fog and one man leaps aboard), Alan Breck Stewart, a Highland rebel, fiercely loyal to the deposed Stewart dynasty.

Stewart is yesterday, as much as the book is (the plot is set in the 1750’s). He is small, determined, vainglorious (‘Am I not a bonny wee fighter?’ he exclaims in a testosterone filled rush after bloodily defending himself against Hoseason’s hapless crew.) Yet he proves to have a shabby nobility and a gritty resilience that David (and we) can only admire. Their journey to Edinburgh, where David finally establishes his inheritance, is a trial of David’s manhood, in which he has his eyes opened in terms of values, loyalty, love, endurance and many other qualities, before the novel’s abrupt ending – with Alan Breck Stewart standing out awkwardly from his natural environment – outside Edinburgh’s British Linen Bank (signalling perhaps that we have witnessed the last guttering flames of heroism in these islands).

Kim, the eponymous subject of Kipling’s novel, is the orphan son of Irish parents in India in the 1890’s, somewhere amongst the Afghan wars of that era. He becomes the chela or disciple of an Indian holy man, but also is inveigled into ‘the Great Game’, spying for the English rulers, principally against the Russian agents who are attempting to destabilise the situation.

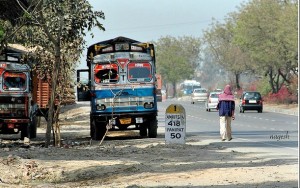

Kim’s journey along the Grand Trunk Road opens his eyes to many things, against a Technicolor background of all that is India in Victorian times.

“All castes and kinds of men move here. Look! Brahmins and chumars, bankers and tinkers, barbers and bunnias, pilgrims and potters—all the world going and coming.”

In the midst of this melting pot, Kim is recognised by the Chaplain of his father’s old regiment by a document that he keeps around his neck. He is then sent away to be educated among the English colonists, with his holy man’s agreement. After three years, he rejoins the lama and travels with him, passing information covertly to the authorities as the lama seeks enlightenment.

Finally, the lama finds the River of the Arrow he is searching for and achieves his spiritual fulfilment. Will Kim follow him, or continue in the service of the English, or try to combine the two? On that subject Kim can only say, “I am not a sahib. I am thy chela.”

These books have obviously similar themes – the journey from ignorance to knowledge, the awakening into manhood, with all its complexity, and the realisation of the difficulties of making moral judgements, particularly when those judgements are of individuals, rather than generalised toward races or nations. David Balfour is no kind of rebel, but he comes to appreciate the values that impel impoverished Highland crofters to pay their dues abroad, as well as to the British state.

Each also has a spiritual dimension: questions are posed, not just about behaviour and what it is to be an adult, but about how to live, how to balance a respect for spiritual concerns with those of the real world and one’s own circumstances. What of course they don’t have is the suggestion of a quasi-sexual relationship between the hero and his companion. While Melville knowingly describes to us the process known as the squeezing of the sperm (in the chapter of Moby Dick called ‘A Squeeze of the Hand’), hints of sexual awakening in these two British novels, such as they are, are resolutely heterosexual. (Encounters with the daughter of the ferryman in Kidnapped and the Kulu woman in Kim are pointers to a sexual future for both).

Both journeys are remarkable for their surroundings – David Balfour’s across the wilds of Scotland (before arriving at ‘civilisation’ in Edinburgh), Kim’s across India, and into the hills, before his lama finds his enlightenment on the plains. Both are set amongst violence and potential disorder, where misjudgements in terms of behaviour will (and often nearly do) have catastrophic effects.

When it comes to critical judgement, Stevenson is often ignored (a children’s writer, famous for Long John Silver, the black spot and the treasure) while Kipling is summarily dispatched (mainly because of his poetic legacy) as ‘misogynistic, racist, and a glorifier of war’. But in these two novels if nowhere else, it seems to me, both rise above those verdicts. And, just to try to make these two unfashionable novels a little more respectable, I can say that Seamus Heaney was fond of quoting Kidnapped as one of his most important influences and Henry James wrote in praise of both.

Perhaps the Victorian era, a time like no other, was one where it was easy to confuse quantity (isn’t there simply too much Scott, Tennyson and Trollope?) with poetry and fiction that requires a little more discrimination, and I would have to admit that certainly there are a number of other works in the Stevenson and Kipling canon a good deal less worthy of respect. Here, it seems to me, these writers achieve something beyond their ‘normal’ selves.

The most powerful aspect of both of these books, it seems to me, is the fact that their endings are beginnings – having learnt lessons, the panorama of possibility opens up to these, now knowledgeable, heroes. Stevenson, finally and unwisely succumbed to the impulse to create a sequel (in the not-very successful Catriona). Kipling had the wisdom to see that pursuing Kim further might only provide a terrible anti-climax.

Whether David Balfour in later life did more than become a good upstanding citizen and whether Kim might later have changed the destiny of history are questions that may well impel the careful reader to re-examine these two novels that seem, to me at least, to stretch the adventure genre beyond its normal limits.

About Michael Spring

Michael Spring lives and works in London, a city that never ceases to provide inspiration of one kind or another. He works for a graphic design agency now, but has been a director of a PR firm, and an award-winning advertising copywriter. He is @dudley_antipope on Twitter.