You have no items in your cart. Want to get some nice things?

Go shopping

I remember a night years ago drinking with my friend Steve: Tecates, shots of rum, shots of schnapps. We were in a bar in downtown Austin, pretending that we were stepping past boundaries, going for, you know, freedom. I remember getting really drunk, and then Steve was throwing the keys to his screaming Kawasaki 1100 on the table in front of me. “There’s a shake in the forks at 114,” he said, “but it’ll smooth out if you ride through it.”

I remember next the rich guttural of the engine in the parking lot, the easy glide out onto the road—and then I was (now I am) on a freeway, past midnight, and wind gushing past, flattening my face, the shake at 114—there it is—rattling the bones in my arms up to the shoulders, and then through it, the dial glowing 120 mph, the little beam of the bike’s light eaten up so fast that road lines and markers snap past, street lights, the vague masses of houses to either side, underpasses, land forms blink, then gone. Pure luck to have lived through that ride, of course. I remember that night now (decades later) as a kind of chill running through the nerves to think of all that was wagered on that nothing of speed. And yet whatever dreams I was nurturing about myself that night, released in fumes of alcohol, a part of me knew even then what tomfoolery it was: I rarely spoke of it to anyone.

I remember another ride a few years before that, again with Steve, my copilot of so many near crashes in those years. It was one of those nights of drifting around, nothing to do, a kind of bored lassitude that was really trapped energy looking for an outlet. I remember saying, I’m hungry, and Steve saying why not drive to San Antonio for Mexican food, and suddenly we were driving south, a hundred miles distant, and once again it was a midnight run. Our destination: a famed all-night Mexican restaurant where a predictable parade of drunken soldiers from the air base, San Antonio mobsters and their mysterious dolled-up women, horn players and accordionists from conjuntos bands, slumming socialites, local ward bosses—in other words, night denizens of all stripes—rubbed elbows and ate tacos together in the pre-dawn hours.

I remember we got lost en route, off the grid, on two lane blacktops that seemed to uncoil endlessly deeper into darkened flat empty semi-arid ranchland, roads that hadn’t seen a car roll past since sunset and wouldn’t see another besides ours until after dawn. Yet we drove on, cheerfully lost, and then suddenly arrived at a crossroads, and there suspended above the intersection swung a massive blinking red light. I remember how we came to a stop and climbed out and stood there, just looking. All around us: the silence of the countryside, its complete emptiness, the traffic light itself, faintly humming, dwarfed by a landscape immense enough to swallow it like a drop, and yet, suspended there above us, unnecessarily massive, clicking on, casting a deep red glow over the asphalt, over the roadside ditches and the barbwire fences that lay just at the edge of sight, and then just as suddenly snapping off and plunging us into total darkness.

I remember the oddly divergent intensities of these memories: one of speed and one of stillness. A pairing that makes me wonder generally about alterations (augmentations?) of reality: aren’t they always, by their nature, forms of erasure, and fundamentally artificial ones at that? I remember another time, this during high school, when over a space of ten weeks I read The Brothers Karamazov, The Castle, and Watt, understanding perhaps for the first time the freedom to be found in the traps that art sets for us. Yet here too emerges an incongruity: for how is the escape literature offered from those grim days of a Texas boyhood different from a drunken night ride on a motorcycle, and are they not equally cancellations of the given world, and was I not in cultivating such evasions—are we not, all of us, (it can be argued) when we make our great escapes—simply joining the “secret lunar societies”, fleeing to “territories infinitely more artificial than society offers us”—these the phrases Deleuze uses in defining the characteristic goals of—the pervert?

Peter Vilbig’s short story ‘Pathway‘ can be read in Litro #134: Augmented Reality.

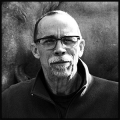

About Peter Vilbig

Peter Vilbig is a writer and teacher living in Brooklyn, New York. He is a former journalist who covered politics, war, and refugees in Central America and later government, crime, and culture in Miami, Washington, D.C., and New York. His reporting from Central America appeared in The Boston Globe, and he was a staff writer for The Miami Herald. His short fiction has appeared in 3:AM Magazine, Baltimore Review, Drunken Boat, Fleeting, Horizon Review, The Ledge Poetry and Fiction Magazine, The Linnet's Wings, Saranac Review, Shenandoah, and Tin House, among other publications. He is currently completing a collection of short fiction.

Must read the full article carefully to get help in changing desktop icons in your windows 10 pc.