You have no items in your cart. Want to get some nice things?

Go shopping

I am an experienced and well published poet yet have had great difficulty in using the personal first person or autobiographical material in my work. My barriers to the ‘I’ are complex I attribute the reasons at least partly to an English working class, post-war, Methodist upbringing where to put oneself forward was considered wrong and the community was more important than the individual. As poet Helen Farish noted in the journal Life Writing, ‘[W]omen have internalized fears of being and saying themselves’.

However, the personal barriers would have been easier to overcome had it not been for my awareness of the critical response, or lack of it, to women’s poetry with autobiographical elements. Gill and Waters, in the ‘Poetry and Autobiography’ introduction to the journal Life Writing, suggest that the critical reception of women’s ‘confessional’ poetry has come to mean that ‘to label a [woman’s] poem as ‘autobiographical’ or to identify autobiographical sources or voices is tantamount to denying its creative or aesthetic value’. This has been perfectly illustrated recently by the magazine Private Eye whose literary reviewer seems to be annoyed by Sharon Olds winning the prestigious T S Eliot prize for Stag’s Leap; the reviewer’s approach is to wonder ‘whether she’s really a poet at all’ and to say that Olds ‘merely cuts up and shapes her chatty memories on the page so they resemble poetry’.

This sort of prejudice against domestic, confessional, or autobiographical poetry does not seem to apply to male poets; Christopher Reid’s Costa Prize winning collection The Scattering was about his wife’s death and Don Paterson’s acclaimed collection Rain includes intimate poems about his children; the Contemporary Poetry Review called the Paterson collection “a poignant and remarkable book”.

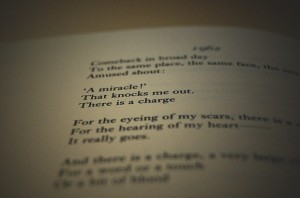

While birth and parenting surely belong with the great poetic themes such as love and death, it seems women can only be accepted as narrators when it is going awry; they can write about miscarriage or death, they can write about failing and being inadequate (and preferably also be suicidal) but a straightforward poetic exploration of the miracle of creating a human being is regarded as something akin to grabbing a stranger’s arm, fixing them with a glittering eye, and forcing them to look at family photos. Kate Clanchy’s book, Newborn, (2005) is a collection of fine poetry about childbirth and motherhood from a skilled and experienced poet; her earlier collections won both acclaim and prizes yet Newborn met with very mixed reviews including an online one reportedly of such misogyny and venom directed at the poet herself that it was taken down as potentially libellous.

The critical reception of any women’s poetry that can be labelled ‘confessional’ has engendered a self-consciousness about the ‘I’ which significantly contributed to my own discomfort in writing poetry in the first person. I am apparently not alone in feeling a need to distance myself from the I in poetry; Deryn Rees-Jones, in her critical work Consorting with Angels (2005), analyses some of the distancing strategies employed by British women writing today to deflect ‘a direct relationship between the ‘I’ of the poet and the poetic ‘I’’ including Carol Ann Duffy through myth and monologue, Selima Hill through surreal imagery, and Alice Oswald by a coalescence of body and nature through multiple voices.

While there are plenty of sources to be found of women writing about the dismissal of any women’s poetry with autobiographical elements, direct evidence is more difficult to track down. In some ways, this is not surprising; we know that women’s poetry is in the minority on the review pages and also proportionately published less (given that more women than men read and write poetry). Publisher Neil Astley, in his 2005 ‘StAnza’ lecture surveyed the Guardian Review’s poetry pages:

‘I went through a pile of over 70 Reviews collected over a two-year period from 2003 up to last weekend. Even I found the statistics shocking. ….. I counted full-length reviews of 66 other new poetry books, but only 10 of those were by women writers. Those 66 books were reviewed by 38 different critics, but only four of those were women’

Blogger Fiona Moore has done a more recent survey of the same publication and, while there has been some improvement since then, there is still gender disparity : from March 2012 to April 2013 the poetry books reviewed were 75% by men and 25% by women (actual figures for last three years available on the blog, URL below).

Both Astley and Moore chose the Guardian to survey; it probably covers poetry more thoroughly than the other UK broadsheets and has a reputation of being left-leaning and politically correct so that it could be assumed the paper would have less gender bias than the more conservative publications. In addition, as Fiona Moore says, ‘because the Guardian is mainstream, reaching a far wider audience than any poetry magazine. People whose acquaintance with contemporary poetry goes no further than skimming the [Guardian] Review’s reviews will have no idea of its diversity.’ ‘VIDA’ counts gender disparity in reviews across a range of publications in the USA, collecting similar results as above with a few notable exceptions.

Given the difficulty of finding reviews of women’s poetry to sample, and given that work dismissed as ‘confessional’ is often rejected, primary written sources of the critical response to such work are extremely difficult to find, with the exception of the couple of examples noted above. Where reviews do show distaste for women’s directly autobiographical work, it is often stated obliquely. A review by Adrien Grafe (2008) praises Helen Farish’s poetry for being ‘subtler, more objective and distanced, and therefore ultimately more moving, than that of some of her sisters and contemporaries’ thus apparently offering a pat on the head to Farish for being ‘distanced’ while, by using the politically loaded ‘sisters’, taking a sideswipe at women’s poetry which is more direct.

Another reason it is difficult to find very much explicit evidence is that the poetry world is small and bears grudges; women who stand up to bring attention to any disparity are usually attacked, often viciously, for daring to question the status quo. Neil Astley’s lecture details examples of such responses. Any discussion there was to be had about this issue had to offer safety and confidentiality.

I use Facebook a lot for poetry networking and chose to use it as a way to approach experienced, published, women poets, and ask them to share any direct experiences of negative responses to autobiographical work. I assured them of confidentiality and that I would neither name nor quote them in any subsequent articles or papers without permission. I sent out 60 requests and received 35 responses; even if those who didn’t respond all had no negative experiences, those who did respond showed a significant proportion with tales to tell. 25 of the 35 responding gave direct examples of negative experiences they’d had with editors, other poets, agents, and tutors. These experiences ranged from tutors refusing to critique work that was too ‘female’ or ‘domestic’ to an editor of a well-known journal stating they didn’t publish ‘confessional’ work. While it is difficult to convey the negativity of the experiences without breaching confidentiality, some of the language used by the critics was repeated in several women’s stories: ‘domestic’ and ‘of no interest’ was the most common, ‘coy’ appeared a few times, while any assertiveness or hint of anger in the poems was described as ‘shrill’.

One woman’s work was described as ‘fluffy’ in a review – not a critical term I am familiar with! These were all experienced poets who understand about submission and publication; they don’t have unrealistic ideas about ratios of acceptance or rejection yet some of them seemed to have been harbouring feelings of frustration, hurt, or anger about these incidents for some time so that being given an opportunity to talk about it opened the floodgates. It is not surprising that poets are left feeling frustrated by criticism that is essentially unanswerable. Any serious writer learns the value of critique and editorial feedback; we learn, especially if we’ve spent any time in workshops, that any critique offered should be accepted without argument or defensiveness whether we agree with it or not and whether we intend to act on it or not. Having one’s work dismissed through a lack or denial of critical engagement effectively and comprehensively disempowers the writer who then has no way of moving past such a barrier.

So why is it so difficult for editors and critics to afford women’s first person poetry a properly thorough critical response? Perhaps because, as poet Rose Kelleher said in a discussion about the negative reaction to Sharon Olds, ‘the universal ‘I’ is male’ and if that is so, then those readers, however unconsciously, will be more inclined to dismiss the work as irrelevant to their concerns and discard it without close reading. The lyric poem, perhaps more than any other, demands the reader submits to it and accepts its world view; Vicki Bertram, in her book Gendering Poetry, describes some of the research which has been done about the effect of gender on readers as well as writers. She describes Sarah Mills’s experiments from Gendering the Reader where she examines both male and female reception of a poem which is an explicitly female lyric poem and shows how male readers struggle to engage with it, suggesting they ‘struggle to find a position from which to read as males’. The alternative for male readers is cross-gender identification which is, of course, possible but as Bertram says, ‘a more unusual experience for men’ while women have had to become used to reading, and identifying with, the male lyric through its prevalence in education, publication, and anthologies.

Whatever gains have been made by women in the publishing world, the default definition of poet is still male; no-one says ’male poet’ because at some level it sounds tautologous and poets who are women are described as ‘women poets’ as if they have to be defined in terms of their abberance, of their not being men. As in the visual arts, in poetry women have traditionally been the object of the male gaze, rather than the artist; the vehicle of the metaphor rather than the creator of it. Poetry has traditionally been framed as authoritative and public; it has been seen as imparting wisdom, philosophy, history, and insight to a passive audience. Law, medicine, politics and other domains that are seen as carrying authority have been strongly defended against incursion by women and the same is true of poetry. One of the most effective defences has been the focus on content, rather than craft, in women’s poetry and the use of that focus as a means of dismissal. The poet Helen Farish, writing about a conference in an article for the journal Life Writing, describes a male poet expressing his relief to be reading with two other male poets because ‘men write about ideas, women only write about themselves’.

Most, if not all, lyric poetry is, at its heart, about the big life issues of love and death; a way to examine and express the mysteries of the human condition. How absurd, then, it seems to limit or dismiss the mysteries at life’s beginning of childbirth and child-rearing or those of sustaining life through feeding and nurturing. This division in themes was strengthened by the Victorian emphasis on separation of the male public domain and the female domestic domain, following the foregrounding of the lyric ‘I’ through the Romantics. Division in themes and domains appears, to some extent, to be self-sustaining; women poets who have managed to established a strong public lyric voice such as Gillian Clarke and Eavan Boland ‘have done so by delineating a specifically female sphere: the neglected matter of women’s domestic lives’ (Bertram, Gendering Poetry). Where critical works include women’s poetry, it is often sequestered to a separate chapter and analysed only in terms of Feminist Theory and not any of the other approaches available. For example, in His Book ‘The Twentieth Century in Poetry’ Peter Childs included chapters on ‘Recent Male Anthologies’ and Recent Anthologies by Women’; however, ‘while the first chapter covers a broad range of issues from Thatcherism to philosophy, the second takes feminism as its central theme’ (Bertram).

What can we, as poets, do about these issues? The disparity in critical response is not universal; there are properly critical reviews of women’s lyric poetry and we need to acknowledge and promote them. When we write reviews, we need to ensure we don’t perpetuate the status quo by concentrating on content but offer thorough analysis of craft and technique. We need to write what we need to write, without fear or consideration of critical response. What we have to say matters and we can say it as women because, as Vicki Bertram writes: ‘Sex and gender matter in poetry. They play a significant part in the way poets write and readers read. As a genre, poetry has proved especially resistant to this idea. To deny this is to facilitate a critical tradition that prioritises and naturalises men’s writing and concerns.’ I agree that it is important, in criticism, to consider something as intrinsic to our identities as writers as sex and gender just as cultural and societal influences are taken into account; however, the consideration of it is not a reason to abdicate responsibility for a properly thorough critical response for women’s poetry as well as men’s. I look forward to a time when our work may be judged on its craft and technique, its metaphor and music, rather than solely on its content, domestic or otherwise.

Further reading:

Astley, Neil, (2005) StAnza Lecture 2005

Bertram, Vicki, (2005) Gendering Poetry, London: Pandora Press

Farish, Helen, (2009) ‘Faking it up with the Truth: The Complexities of the Apparently Autobiographical ‘I’’, Life Writing, 6 (1)

Mills, Sarah, (1994) Gendering the Reader, Harlow, Prentice Hall

Moore, Fiona, (2013) Poetry and Sexism in the Guardian Review

Rees-Jones, Deryn, (2005), Consorting with Angels: Essays on Modern Women Poets, Tarset: Bloodaxe Books

VIDA count

About Angela France

Angela France works for a youth charity and lectures creative writing at the University of Gloucestershire. She has an MA from the University of Gloucestershire and is studying for a PhD. Her publications include ‘Occupation’ (Ragged Raven Press, 2009), ‘Lessons in Mallemaroking’ (Nine Arches Press, 2011) and her latest collection, 'Hide' (Nine Arches Press, 2013). Angela is features editor of Iota and runs a monthly poetry cafe, ‘Buzzwords’.

One comment