You have no items in your cart. Want to get some nice things?

Go shopping

Start from part one of this series.

We trudged through the grey town, our faces sprayed by drizzle no matter where we turned. I was in a foul mood, which the blandness of the place, coupled with the annoyingly present weather like a child incessantly badgering us, did nothing to assuage. It had to happen sometime. It wasn’t possible for our dream honeymoon to go off without a hitch. What with four weeks of travelling across a land totally alien to us, only in each other’s company for ninety per cent of the time, we were bound to hit a bump in the road. I tried to rationalise this in my mind at the time, but nothing worked. I couldn’t help myself. I resented my husband for Tokushima.

It was only meant to be a stop along our journey from Osaka to Japan’s southern island of Shikoku. Surprisingly, few tourists venture to this island, and our own introduction to it made me question if we were doing the right thing by “going off the beaten track”. Maybe the track is so beaten because it’s the most worthwhile.

The day started badly. Having been broiled overnight by our hostel’s Amazonian climate, we rushed with diminishing energy to the bus station. Thankfully, we had spent over an hour trying to locate it the evening before; that reconnaissance helped us to make it in time. We boarded a coach to Tokushima, which cost far too much for my liking. My liking only descended from there. I realised precisely how much we’d overpaid when I spotted the Japan Railways logo as soon as we took our seats. We hadn’t even needed to buy tickets at all – our JR passes, which I’d spent a week so far guarding like a hound, would have covered the journey.

“It didn’t say this was a JR coach anywhere at the ticket office!” my husband pleaded in his defence, but I was already beyond listening to reason. Not only had I lain awake all night sweating instead of sleeping, but I had also just got the news we’d wasted money we couldn’t afford to waste. This town had better be worth it.

It wasn’t. I try never to judge a place on first impression, but in Tokushima I relaxed those rules. Featureless grey blocks gathered around personality-free streets. My eyes caught a palm tree and clung to it – the only pleasant thing to look at in this dull town. I was aware of being immature in my silence. I knew I should at least talk to my husband before he tired of me and abandoned me here. But I was so worn out and annoyed by the whole morning that I couldn’t muster the energy even to speak. We made a mistake, so what? We shouldn’t have come to this dreary dump, but worse things have happened in life. I was beyond help. Every little thing annoyed me, even the traffic lights, which looked as if they were meant for cars but were facing our way. Was it green for humans or vehicles? Did it matter? There were no cars here. Not even the locals wanted to be here. We were the only visible beings for miles.

The reason we were here? A dance. The Awa Odori takes place out on the streets during O-bon, the Buddhist festival when spirits return to their family homes. It is said that in 1587, a feudal overlord threw a party to celebrate the completion of his castle (not that I could see one). His guests got so drunk they launched into a limb-flailing frenzy approaching a dance. This Dance of Fools then turned into an annual event, and has been kept alive since. We were in Tokushima to visit the Awa Odori Kaikan hall, a cultural centre featuring a small museum and a demonstration of this unique ritual.

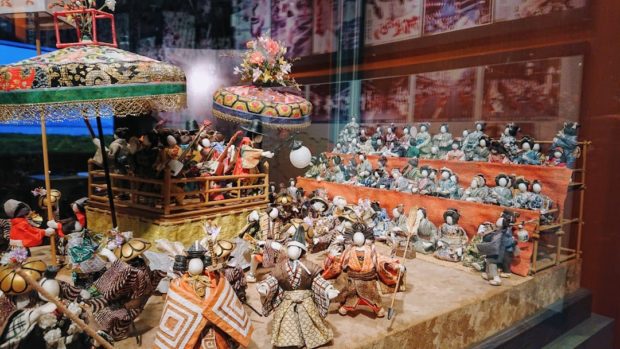

In fairness to Tokushima, things picked up here. The hall sits at the base of the verdant mount Bizan, offering a cable-car “Ropeway” for aerial views of the city. While we waited for the afternoon performance of the dance, we browsed the museum, full of figurine re-enactments of the ritual over the centuries. The low ticket cost was a huge compensation for the unnecessary travel fare we’d incurred, so I began to ease up. I’m not a stingy individual at all; my lack of money denotes my carelessness with it. But I battled a strong sense of injustice at being victimised. I now gradually came to see Tokushima not as a bad town, but simply an ordinary one. Its only offence to me was that it seemed a perfectly inoffensive place for an admin worker in the ’80s to inhabit a small flat. Was I annoyed that our trip-of-a-lifetime had thrown up a slice of real life, as opposed to a living postcard? If that was the case, then what purpose did I seek in travelling? Exposure to other cultures, including warts-and-all daily routine, or just something pretty to put on Instagram? Even this observation annoyed me.

We entered the main hall for the performance. There were hundreds of seats; I wondered how they’d be filled. And yet, to my surprise, people started to file into the auditorium until, eventually, there was a sizeable audience. Where had all these people come from?

The compere, a jovial man who went down a treat with the Japanese speakers, eventually asked that question aloud. That was when a cold ripple went through me. I hate audience participation; it’s the most English thing about my Cypriot self. I always sit near the back of a room, just in case, even if that room is the O2. My husband and I cringed and clenched, but of course it was only a matter of time before the compere gestured to us, two of the six white Westerners in the room, and asked us in English where we were from.

“England,” we replied, which he didn’t catch.

Someone closer to the stage piped up with a translation. This person was a young, fair-haired Australian, who proceeded to be interviewed by the excited compere. And she replied in his language, totally showing us up. How had I learned to say “station stamp” in Japanese, but not what country I had travelled from?

While the compere gave a history of the Awa Odori, an English translation was projected behind him. He talked us through the instruments that made up the backing music, and each was demonstrated by a member of his company – o-daiko, a booming large drum; shime-daiko, a smaller, higher-pitched drum; fue, a flute; and kane, a gong. We learned about the costumes worn by the male and female dancers. The women looked especially impressive, what with their pink and blue crepe-silk kimonos, geta (traditional clogs) and, most arresting of all, their Torioigasa; circular straw hats folded in half, and worn so that the front part shrouds the wearer’s face in shadow while the back tilts upwards to expose the nape. The hat is thought to have the dual function of attracting men while repulsing birds in the fields.

The lights went down, and the dance began. Against a backdrop of sunset hues, the dancers moved to the upbeat drum-and-flute music, roaming the stage as if in a street procession. With alternating hand movements above their heads and leaning forward on the tips of their platforms, the women called back to the words of the men (“Yattosa! / A, yatto, yatto!” – “It’s been a while, how are you?”). It was a mesmerising spectacle.

At the end of the performance, I was snapped from my trance by a nightmare. Audience participation had reared its ugly head again. The dancers came through the stalls looking for volunteers to learn the dance. I all but pushed my sacrificial husband at them. Dancing in public is more his sort of thing. There he was, tall and blonde and learning fast on that stage while I sat so far back in my near-the-back seat that I was practically one with the upholstery.

As if the audience participation wasn’t enough, an award ceremony followed it. The award for best dancer went to the Australian girl who’d spoken Japanese with the compere. I sat there, removed and guarded, but joining in the applause. I’m certain her reward was well earned.

Polis Loizou’s debut novel, Disbanded Kingdom, is out now.

About Polis Loizou

Polis Loizou is a co-founder of The Off-Off-Off-Broadway Company, which primarily performs his plays, and has had a series of successes since their first hit at the Buxton Fringe in 2009. His short stories have been featured in The Stockholm Review of Literature and Liars’ League NYC, and he is a frequent contributor to Litro Magazine. Born and raised in Cyprus, Polis is currently based in Nottingham after 14 years in London. 'Disbanded Kingdom' is his first published novel. He is currently represented by Litro's bespoke literary agency, Litro Represents.

- Web |

- More Posts(25)