You have no items in your cart. Want to get some nice things?

Go shoppingWith the release of his own sci-fi thriller, Plastic Jesus, author Wayne Simmons looks at what makes good dystopia.

Good friend and fellow hack, David Moody, describes ‘horror’ as an emotion, not a genre. It’s something you feel, something you suffer, as opposed to that dusty old shelf at your local Waterstone’s with all the books nobody wants to read.

But could the same be said for dystopian fiction? Is there a formula for this oft-ignored sub-genre, or is it more of a feeling, something a book either has or doesn’t have?

As a writer with four horror books on shelves, that’s a question I’m asking myself. My latest book, a sci-fi thriller entitled Plastic Jesus (Salt Publishing), is being described by some reviewers as dystopian and I’m wondering what exactly that means. Is it something I meant this book to be? Or is it just something it has become, with little or no help from me.

Like horror, dystopian fiction has its flagships; 1984 by George Orwell, A Clockwork Orange by Anthony Burgees, maybe even Neuromancer by William Gibson. And then you have the hidden gems such as Divided Kingdom by Rupert Thomson or Battle Royale by Koushun Takami. And it’s interesting because when I think of each of these very different books, I get the same colour in my mind: grey; I see smoke rising up from a jarring cityscape, I hear synth music in minor key. Because, when it all boils down, the most perfect example of dystopia, for me, is not to be found in literature, it’s to be found in film. One particular film, in fact: Ridley Scott’s Blade Runner.

Of course, Blade Runner is itself based on a book. It’s the adaptation of Philip K. Dick’s classic novel Do Androids Dream of Electric Sheep? But, in reality, they’re both very different: they feel different, for one thing; Do Androids Dream of Electric Sheep? is quite an offbeat and peculiar read, bordering on the absurd with its story of a society starved of reality, obsessing over cyber-pets, while Blade Runner is more like the noir of Raymond Chandler or James M. Cain; Harrison Ford’s somewhat muted performance as the trench-coated Rick Deckard echoing the chain-smoking, hard-drinking PIs of the 40s and 50s.

For my own take on dystopia, latest novel Plastic Jesus (Salt Publishing), it’s the smoke and cityscape and synth that I want. Essentially, this is a tech noir novel; the blending of low-life and high-tech; my love letter to Ridley Scott for Blade Runner, but also William Gibson for Neuromancer as well as a host of noir and neo-noir writers through the ages (Lawrence Block, Day Keene, Donald E. Westlake, Christa Faust etc.)

![2512_10151363704442181_2110671363_n[1]](https://www.litromagazine.com/wp-content/uploads/2013/11/2512_10151363704442181_2110671363_n1-300x460.jpg) The story takes place in Lark City, a sprawling neon metropolis set on an island off the coast of Total America. Lark is divided into four quarters: a business quarter known as Titanic; an industrial quarter called River; the more rundown side of town, known as Queens; and finally the old part of the city, known as Cathedral Quarter, with its tattoo parlours and smoky jazz clubs, as well as the city’s last remaining church. Tomb Street is Lark’s red light district, weaving through the city like a snake, soaking up style and clientele from all four quarters, an endless troupe of dancers and street performers parading like marionettes.

The story takes place in Lark City, a sprawling neon metropolis set on an island off the coast of Total America. Lark is divided into four quarters: a business quarter known as Titanic; an industrial quarter called River; the more rundown side of town, known as Queens; and finally the old part of the city, known as Cathedral Quarter, with its tattoo parlours and smoky jazz clubs, as well as the city’s last remaining church. Tomb Street is Lark’s red light district, weaving through the city like a snake, soaking up style and clientele from all four quarters, an endless troupe of dancers and street performers parading like marionettes.

We meet Johnny Lyon, a Code Guy (read programmer) who is tasked to write a controversial new programme for release via Virtual Reality. His employers, Alt Corp, hope that this new VR will speak to something deep within people, a yearning they didn’t even know they had. Lark City’s out of control, they say, with its drugs and prostitution and obsession with excess. Its people need a new addiction, something that will rein them in, give them a high that no drug will ever give them: they need religion.

And here’s the rub: for true dystopia, you need a failed attempt at utopia. It’s the contrast that makes the whole thing work. With Blade Runner, it was the basic cyberpunk hook: man invents machine; machine turns against man. With Plastic Jesus, it’s about religion: man invents religion, religion turns on man. Man tries to rebrand and reinvent religion using machine and… needless to say, things don’t go according to plan.

Of course, as a writer, I’d say Plastic Jesus is primarily about the characters – a varied bunch of disconnected and disenfranchised anti-heroes brought together through the repercussions of the Jesus programme’s launch, and their reaction to such. And that’s another thing I’ve learned about dystopia: it has to have a strong cast. It won’t work without it. And they can’t be happy campers, either: no, our cast must be surly types, beaten down by the system, almost – but not quite – ready to give up and give in.

In Plastic Jesus, there’s Johnny himself, who we meet in the prologue, standing by his dying wife’s bedside. Sometime later, we’re introduced to Kitty McBride, a crack whore who picks Johnny up from Vegas, where he’s drowning his sorrows. Kitty’s the daughter of druglord, Paul McBride, a Koy Town (think Deep South) gangster with everyone in his pockets. Reverend Shepherd is the last working cleric in Lark City and childhood friend of Paul McBride. Due to an unpaid debt, he agrees to store dope for McBride in the back storeroom of his church. Ex-addict, Rudlow is a trench-coated cop with a personal vendetta against McBride. With the help of his lover, an old-school brothel Madame named Dolly Bird, Rudlow strives to take the gangster down.

And then there’s the sci-fi element, often a bedfellow of dystopia. Plastic Jesus is set within the near future, 50-odd years from now. The story employs the cell phone as essential tech, a one-stop-shop for connection to the Net, wirelessly syncing APPs to do just about anything in the real world, from switching on lights to paying for drinks. The cell also provides access to virtual reality, pure unadulterated escapism. This requires the user to physically plug their brains into the cell using tech known as a wiretap and coil.

Are you scared yet? You should be: we’re not far off all this with our growing obsession with social networking and smart phones doing just about everything short of raising Jesus from the dead. And that’s dystopia too: a glimpse at what could be; the tyranny of 1984, perhaps, or brutality of Battle Royale or, indeed, Blade Runner.

But let’s not get too carried away. Plastic Jesus may qualify as dystopian fiction, and it may even hit upon some contemporary themes, such as the evolution of smart phones and social networking, but are these really things to be fearful of? Let’s face it, dystopian fiction isn’t exactly the Nostradamus of the literary world. See any robots in government yet? Japanese schoolgirls with machine guns? Exactly. You see, when it all boils down, a dystopian novel or film may say more about its writer than the world around him: it takes a certain type of miserable bastard to pen this stuff. Ever seen Ridley Scott interviewed? Not the cheeriest fellow. Blade Runner was a troubled shoot, by all accounts, both Ford and Scott reported as difficult to work with. Now, on the face of it, I consider myself quite an affable sort; I’m not your average artiste, disappearing up my own arse for large parts of the day. But I’m no Pollyanna, either, that’s for sure, and it wouldn’t take a shrink to spot little bits of my own psyche within this book: the hang-ups with religion; that lingering shadow of guilt; an underlying misanthropy, perhaps?

But we do need dystopia. Just as much as we need utopia. It’s the yin to our yang, the fears to our hopes, the flip side of an ever-spinning coin. And while dystopian storytelling is important, it’s also entertaining: I’ve just picked up the blu ray edition of Blade Runner: The Final Cut. The film’s had more editions than a ten bob note and there’s something to be said for that. It’s just about my favourite film in the world so to have my own work even mentioned in the same sentence as Ridley Scott’s seminal masterpiece is nothing short of humbling.

And maybe a little scary…

Plastic Jesus is available from Foyles for Books and all good bookshops.

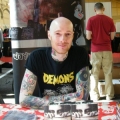

About Wayne Simmons

Belfast born, Wayne Simmons has loitered with intent around the genre scene for some years. He penned reviews and interviews for several online zines before publication of his debut novel in 2008. Wayne’s work has since been published in the UK, Austria, Germany, Spain, Turkey and North America. His bestselling zombie novel, FLU, was serialised by Sirius XM’s Book Radio. He continues to write reviews and features for various magazines as well as his own website and The Lair of Filth blog. He’s the co-host of extreme metal show, Doom N’ Gloom, and has his own podcast, HACK. He co-produces the Scardiff Horror Expo. Wayne’s forthcoming novel, PLASTIC JESUS (Salt Publishing) is a sci-fi thriller that’s been compared to Ridley Scott’s BLADE RUNNER and Christopher Nolan’s INCEPTION. Visit Wayne online at www.waynesimmons.org.