You have no items in your cart. Want to get some nice things?

Go shopping

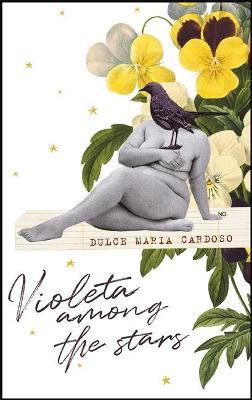

For most readers, the one-sentence novel is reminiscent of James Joyce’s trademark stream-of-consciousness technique. Certainly he isn’t the only one who just will not end his sentences, but the sense of urgency that the technique lends to Dulce Maria Cardoso’s novel Violeta among the Stars is in no way comparable. But let us start at the beginning – a dark and stormy night. Violeta is on a business trip, travelling on a lonely road, and the almost inevitable accident happens. As she is strapped into the car seat, hoping for help to arrive, she sees her life flashing before her eyes. Soon it becomes apparent that Violeta will soon rest “among the stars,” and we get to share a glimpse of her diverse “freakish” inner life, ranging from her often-strained relationship with her daughter, her more than strained relationship with her family, her job, her sex life, and, lastly, her own death. It is a picture of an altogether unremarkable life in about 400 pages. Yet the writing is all but unremarkable.

“remember what happened to the thief who stole the full stops” – the thief was left with a mesmerising account of Violeta’s rich inner life. I was unsure of the writing at the beginning, the style being unfamiliar and Violeta’s own thoughts often being interrupted by other people’s thoughts. It is a deliberate fracturing of both narrative voice and plot that can make the musings about her estranged and difficult parents, her disappointing life, her own dislike of her body, and the absolute adoration of her daughter, who is “the most perfect part of me,” difficult to follow. It is a monologue, almost like a poem, that leaves one tired and drained, at times unable to follow the train of thought. There is no picking-up of pace, and the novel is filled with repetitions and at times slightly odd phrasings.

However, it offers a steady reading experience that lures readers in without their noticing: Somewhere along the line, you will find yourself unable to put it down and the pages will be flying by like Violeta’s quick sexual encounters. The repetitions and breaks in reading that had made it difficult to immerse oneself in the story at the beginning soon put you in an almost trance-like state, in which everything but Violeta’s consciousness begins to fade away. Her almost feverish accounts of her life up to the accident draw the reader deeply into a life that seems so simple at first glance but is overshadowed by an all but picture-perfect family life. Even though Violeta is clearly the focal point, it becomes ever clearer that her daughter is both the troublemaker and the saviour in her life and the life of her own deceased parents.

The most remarkable aspects in Violeta’s life are certainly her personal relationships. As a travelling salesperson for waxing products, she prides herself on her knowledge of both products and customers. Women’s body hair is her sworn enemy, a million-strong army that only the products she sells and her own knowledge can defeat. Even though the pride in her work is obvious – work which brought her into the fatal storm in the first place – Violeta is constantly worrying about her customers only buying from her out of pity. While Angel is, at least at the beginning, made out to be her life partner, she constantly belittles him and his career. He is a mediocre comedian, at best, and the funniest jokes he has to offer are repetitions of what the hecklers on senior citizen days out have to say about him. Of course, this relationship is complicated by a million unsaid things that only come to light gradually over the course of the novel.

The second anchoring relationship in the novel is Violeta’s family life. Her mother, who dabbled in French to raise her social standing, and her father, who slowly slipped into madness and only spoke to his birds the further his mental decline progressed, seemingly had little love left for their daughter with all her imperfections. This relationship, too, is mirrored in an inanimate object, namely the house of Violeta’s parents. This house, beloved by her daughter but disliked by Violeta, causes the last fight between mother and daughter, after Violeta sells the house that is seemingly closing in on her. Only through the voluntary loss of the house is Violeta able to partially reconcile her parent-daughter relationship. Both relationships seem to be based on crudeness and cruelty, but the more insight the reader gains on Violeta, the easier it becomes to pinpoint and differentiate her thoughts and feelings.

Dulce Maria Cardoso’s writing is a force to be reckoned with. While at the beginning the stream-of-consciousness technique might not work out for every reader, it is a structural reflection of Violeta’s life. The frequent stops and interruptions reflect upon the way Violeta’s life was not a one-way street; her life itself was filled with forceful stops and repetitions, misunderstandings and intriguing personal relationships. Parallel to her thoughts constantly circling back to her daughter, she increasingly seems to become the glue that binds the narrative together. As the narrative picks up the loose ends it previously hinted at, Portugal’s contemporary history and everyday tragedies are woven into a heart-wrenching account of a life that we can all envision in our own relationships and our own contradictions and conflicts.

A word on the translation has to be said as well. Both the translator Ángel Gurría-Quintana and Cardoso herself are true masters of their craft. While there are a few instances in the translation that could have been phrased differently to ensure a smooth reading experience, writing still reads compellingly in English. My personal impression was that the few pages where the translation was not as successful do hinder the reading experience but not in any lasting fashion.

Certainly, Violeta among the Stars should be approached with a mind open to less common narrative forms. It is neither an entertaining read nor an easy afternoon or poolside novel. Apart from an openness to its form, this book demands constant attention and the willingness to immerse oneself in Violeta’s monologue. I would argue that Violeta among the Stars is a wonderful example of the lasting impression form can leave beyond content. The novel itself is an artistic achievement in style and form that will move you, even if you don’t want it to. It is an extraordinary piece of writing on the life of an ordinary woman.

Violeta among the Stars

By Dulce Maria Cardosa

Translated by Ángel Gurría-Quintana

MacLehose Press, 396 pages

About Raphaela Behounek

Raphaela Behounek is a PhD student at the University of Salzburg, Austria, currently researching in the field of young adult fiction and fantastic fiction. After completing a BA in English and American Studies, she went on to earn her MA in Literature from the University of Essex, UK. Her research interests are Fantastic fiction, the fictionalisation of institutions and power relations, as well as literature in popular culture. A key area in her work is not only teaching literacy, but also how literature can transcend the page and offer real-life impulses.