You have no items in your cart. Want to get some nice things?

Go shopping

M.J. Nicholls’ Trimming England takes the reader on a journey through an alternate England led by people who think it’s a good idea to “trim” the country of its more colourful inhabitants. The book opens with an introduction from Nicholls, writing in the year 2023. He has won a free holiday in Jersey from a Munch bar, but the hotel he will be staying in, the Hotel Diabolique, is famous for its “discomfort” and prides itself on giving its guests a terrible experience. Its only visitors are “masochists, sex tourists, and contest winners,” all of whom are apparently fine with paying £10.99 for an uncooked sprout.

There is, however, one other group who stays in this hotel. Contained within its walls is a “prison for public nuisance offenders,” which currently holds 47 people. Nicholls explains that, in 2021, British Prime Minister Frank Oakface devised a scheme to improve life in England’s 48 counties. The “largest irritant” in each county would be identified via online polling and then incarcerated for a duration dependent on the supposed severity of the irritant’s crime. Nicholls decides to accept his prize and go to the Hotel Diabolique. Once there, he meets all 47 inmates of this “irritant-cleansing scheme” and sets about recording their stories. The chapters that follow are those stories, recast in “more palatable and vivid literary styles.” Each chapter is named after the part of England from which the irritant was trimmed. The sentence is recorded, spanning a few hours to a few decades, and the crimes, which range from “seeking sympathy” to lobotomising children for profit.

In the opening chapter, Tyrone Pouch, a writer by trade, takes to social media to express his frustration with a bout of writer’s block: “I lapse into creative coma.” The post is well received – 50+ likes – and the next day Tyrone indulges himself again: “Verily, I sink into a trough of brain-mush.” But he loses his “core base of likers,” and the reason soon becomes clear to him: He expressed his “impotence in a creative way, hinting to the reader [he] was merely pretending” to have writer’s block. He then tries to salvage his reputation as a terrible writer: “I cannot write a single pissing thing.” But it’s too late, and the comment section is littered with “faux-concern.” Tyrone resorts to “writing lengthy retractions” but they fall on deaf ears. He then commits to stop being “a writer writing nonwriting about not-writing,” but before he can put his resolution into practice, he is incarcerated. Sentence: two years. Crime: “abysmal second status.”

This first case establishes the book’s preoccupation with writers and their writing, a pattern that is acknowledged by Nicholls in his introduction, blaming it on the current social climate, which is a “time of deep-seated anti-intellectualism in the country.” In a later chapter, we meet Hector Lettsin, who is tired of being published in “small unprofitable low-circulation presses” and in need of an agent. He submits his “highly literary new novel” (entitled My Highly Literary New Novel) to several agents, and eventually bags Sam Ruple, who has no scruples about transforming Hector’s novel into “a breakthrough big whopper.” Hector agrees to abandon his plan to spit on “the tired conventions of the novel” and instead embrace “likeable” characters and the whimsical opinions of focus groups. Sentence: 79 years.

Further on, in Shropshire, Simone Slaph’s debut novel, Love Among Bedwetters, is about to be published, but there’s a catch. You see, for an author to survive in today’s market, she must have a “niche.” If Simone goes ahead with her debut, she will need to embrace the mantle of “that bedwetting author.” Simone weighs up the pros and cons: having recognition and an income vs. “having strangers think she is a bedwetter.” She decides to make her bed and, indeed, wet it. Her second novel, Bedwetters in Borstal, is about “prisoners who piss themselves.” Crime: “soul for hot piss.” Sentence: eight years.

These tales from the world of publishing will almost certainly bring a knowing smile to the face of any writer (They did to this reviewer.) But the wit that accompanies these observations should be enough to entertain even those who have never heard of the Writers’ and Artists’ Yearbook. Delving deeper, behind the charming absurdity, is a thoughtful analysis of the literary novel in modern publishing (For poor Simone, even the term “literary” is too literary and has to be replaced with “easypleasy.”) And because the starving artists and publishing establishment are both represented at their most excessive, one is not left feeling a bias in favour of one over the other. Both can be reasonable and irritating in equal measure.

For those not amused by scribblers and their scribbles, there are plenty of other characters being trimmed from England. There is the magazine editor who confuses “novelty teacosies” with “Heinrich Himmler action figures” (naturally, an easy mistake to make), and the man who starts a local campaign to turn a woman’s living room into a public toilet, all because she “tutted hard” when he bumped into her along Porthmeor Beach. A mystery criminal is sentenced for an unspecified time for daring to suggest, in a public forum, that Manchester might be renamed Squidgieroonienips, and Frank Fitch gets “11 furlongs” for letting the world know that he’s been to a tree that appeared in “Escape to the Country East Sussex,” along with several other insufferable YouTube comments.

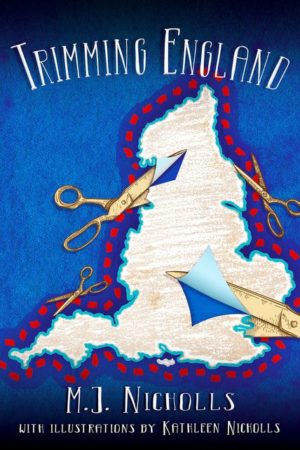

Accompanying the text is a series of illustrations by Kathleen Nicholls that shows a map-like outline of the region of England under observation and, within the region’s parameters, the drawing of an object or character featured in the chapter. The simplicity of these drawings – nothing more than black lines against a cream background – adds to the sense of intimacy developed in the text. They are doodles of a kind one might make in a diary, little memorials to the bizarre. And Trimming England is, if anything, a monument to the bizarre, describing a world in which a mother tells her son that his father has died by texting “YR FTHR HD HRT ATTACK. DID NT SRVVE. PLS CM HM.” Understandably, she must have had a lot on her plate. Though some readers might find the lack of a single narrative disjointing (The book can seem like a collection of intriguing but independent short stories at times, which is of course the intention, hence the novel being presented as edited and introduced by Nicholls rather than written by him), the landscape of Trimming England is so well defined and consistently wound into the fabric of each mini-narrative that immersion comes naturally. Indeed, the episodic nature of the book, coupled with its quirky tangents and playful dialogues brings to mind John Kennedy Toole’s A Confederacy of Dunces. As in Toole’s satirical novel, Trimming England is not just a showcase of strange “irritants,” it’s also the documentation of a society. For Toole, the society is New Orleans. For Nicholls, it’s England. And for all its absurdity and inventiveness, there is, in a way, a quaint Englishness to many of the characters and their stories, underdogs struggling against the wrath of mundanity.

Trimming England presents the reader with a world that is both incredibly strange and all too familiar. The novel’s imaginative premise is its initial draw, but its cast of characters will take you to the end. One after another, these 47 prisoners keep the reader’s attention with their mannerisms and reasoning on subjects that combine the unusual with the everyday. It was a good thing Nicholls won that contest, though one can’t help wonder if winning it was more than mere chance. Was Nicholls the 48th condemned irritant? If so, through writing this book, he has more than repaid his debt to society.

Trimming England

By M.J. Nicholls

Sagging Meniscus Press, 256 pages

About Robert Montero

Robert Montero is a London-based writer whose work has appeared in South Bank Poetry and London Grip, among others. A novel he wrote was long-listed for the Exeter Novel Prize.