You have no items in your cart. Want to get some nice things?

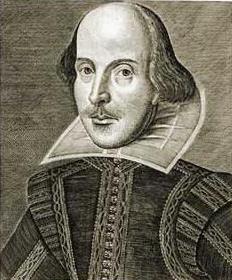

Go shoppingThis week I went along to the London Review Bookshop to hear American academic James Shapiro answering questions on his new book, Contested Will: Who Wrote Shakespeare?

I was hoping for a bit of argy-bargy, an audience packed with Shakespeare doubters, maybe a bit of refined academic heckling, but Shapiro seemed to be pretty much preaching to the converted. Nevertheless, it was an interesting hour. For the last hundred and fifty years, an ever-growing list of people, invariably royal, noble, distinguished or exciting in some way, have been put forward as the true author of Shakespeare’s plays.

I was hoping for a bit of argy-bargy, an audience packed with Shakespeare doubters, maybe a bit of refined academic heckling, but Shapiro seemed to be pretty much preaching to the converted. Nevertheless, it was an interesting hour. For the last hundred and fifty years, an ever-growing list of people, invariably royal, noble, distinguished or exciting in some way, have been put forward as the true author of Shakespeare’s plays.

It all started when an 18th-century scholar local to Stratford-upon-Avon went searching for books or papers belonging to Shakespeare and drew a blank. The conclusion he leapt to was that this absence of the trappings of a learned man must mean that Shakespeare was not a learned man, and that as only a learned man could possibly have written the plays, ergo, Shakespeare, son of a mere glove-maker, was an imposter.

It took a hundred years or so for this theory to catch on, but by the 19th century the idea that Shakespeare was an uneducated fraud who couldn’t spell his own name, let alone write the masterpieces of the English language, was rife. Mark Twain, Sigmund Freud, Orson Wells and Sir Derek Jacobi are among the notable names who’ve signed up to this anti-Stratford camp.

Rather than looking in detail at the contenders for the real Shakespeare, Contested Will instead examines why the question exists at all. It’s a weird one – why is the belief that Shakespeare didn’t write Shakespeare so prevalent, and why does it attract such ardent disciples? Is it down to sheer snobbery –the conviction that such brilliant writing must be the product of an educated, upper-class mind? Is it a modern love for conspiracy and esoteric secrets? Or is it because we have so few details about the life of the best-known English writer that we feel compelled to fill in the gaps using the only material available to us – the plays?

The argument seems to come down to the devil in the detail of the plays. How much of what Shakespeare wrote could he have made up, or got from books, and how much would have to come from experience? Could a man who’d never travelled to Italy have written the plays set there? Or, as another case in point, proponents of the Earl of Oxford as the real Shakespeare use the fact that the earl had three daughters and was once captured by pirates as an indication that he’s a more likely author of King Lear and Hamlet than the man from Stratford.

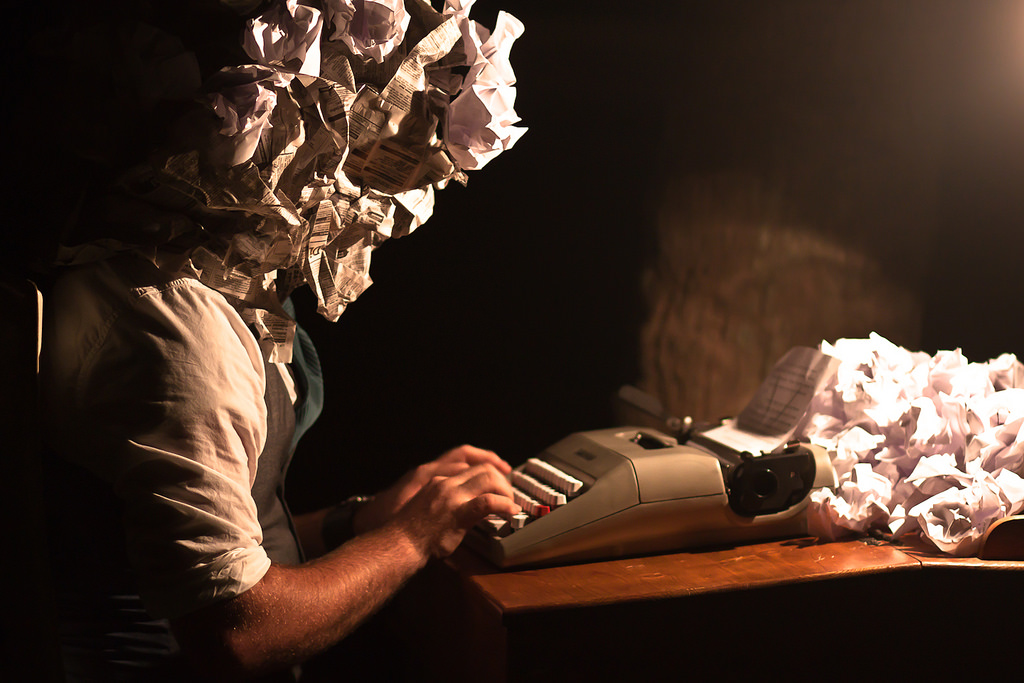

But Shapiro makes the case for the power of the imagination as the truth behind the mystery of Shakespeare’s plays. It’s a reassuring conclusion for anyone who’s ever hoped to write convincingly about stuff that hasn’t actually happened to them, whether it’s setting a story in a country they’ve never visited, writing from the point of view of a murderer, flying to other planets or turning into a werewolf.

The compulsion to read an author’s life into their work seems a basic one, as rife among modern authors as Elizabethan ones. Shapiro quotes T.S. Eliot, who commented that he was used “…to having my personal biography reconstructed from passages which I got out of books, or which I invented out of nothing because they sounded well; and to having my biography invariably ignored in what I did write from personal experience.”

And Lorrie Moore, quoted in this weekend’s Guardian Weekend talking to the Guardian Book Club, wondered whether there was a current trend for writers, especially women writers, to be routinely suspected of autobiography, with readers “determined to think of fiction as a mere route to memoir.” Moore’s stories, which often deal with marital breakdown and terminal illness, are frequently scanned for evidence of trauma in her own life, a process Moore tries to steer clear of.

It’s as if we’re getting fiction muddled up with the real-life memoir section at Waterstones, searching it for truth in the sense of what a writer has experienced on a literal level, rather than a deeper and more widely applicable truth that can come out of stories a writer dreamed up.

Personally, I come down on the side of those like Shapiro who maintain that you don’t need to have three daughters yourself to write convincingly about sibling rivalry, or have been kidnapped by pirates to imagine such an event taking place. It’s a case all writers who believe in the capacity of made-up stuff to contain truth should get behind.

About Liz Cookman

Liz is a thoroughly London-centric writer and a recent addition to the Litro Online team. She is passionate about creative non-fiction and waffles on a lot about London and the River Wandle - a total river bore. She holds a BA in Creative Writing and is studying for an MA in Travel and Nature Writing from Bath Spa University.