You have no items in your cart. Want to get some nice things?

Go shopping

Until quite recently, editors were portrayed by disgruntled authors as pompous, tight-fisted and brutally interventionist, as if these three characteristics were somehow a minimum requirement for the job. This species of editor was best illustrated by Mark Twain’s caricature of a man armed with his carving-knife and tomahawk, gleefully cutting away at everything “smart”, but which he deemed superfluous, in a manuscript.

Today, for the most part, these editors seem no longer to exist. In fact, since Blake Morrison’s long essay on the demise of interventionism in 2005, it has become almost a truism that British editing has disappeared. Articles bemoaning the decline in editorial standards, like those on the death of the novel and the irrelevance of the Booker prize, are now an annual event. As an explanation, the writer usually describes how the modern editor’s schedule is so crammed with meetings and administration that there is rarely time for nurturing new talent—mostly, promising manuscripts remain what they are: promising. What has also been in question is whether editors today have the nerve to edit literary heavyweights and “big brand authors”. As Jan Moir pointed out in a review of J. K. Rowling’s The Casual Vacancy for the Daily Mail, the book’s unnecessary length might be put down to the editor’s timidity: after all, “who would dare to edit the most successful author in the world?”

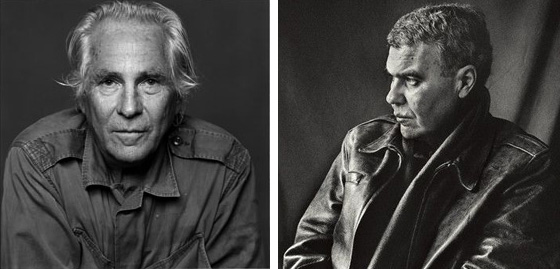

Gordon Lish would have. At the dawn of the 1980s—that decade most often blamed for the corporatisation of publishing and editing’s subsequent decline—he recognised the importance of intervention. When Raymond Carver delivered to Lish his second collection of short stories, then entitled Beginners, the Knopf editor promptly drew his scythe: story titles were changed, plotlines altered, endings rewritten. The edited manuscript was only a little more than half as long as the original, barely the same book.

Lish, a former fiction editor at Esquire and an early champion of Carver’s work, was a close friend of the author. Despite feeling indebted to Lish for his earlier collection, Will You Please Be Quiet, Please?—Carver said grandly, in a letter to Lish, that he already owed “some degree of immortality” to him—Carver clearly felt that his artistic integrity was being compromised in Lish’s edits to his second collection and asked him, in a desperate plea, to “do the necessary things to stop the production of the book”.

“I’ve got to pull out of this one,” he begins in the same letter, appealing to Lish to otherwise let the original manuscript stand, albeit with some changes brought over from the edited version. “Please hear me… My very sanity is on the line here.” Such transformative changes would inevitably raise questions about the work’s authorship, and this was something Carver doubtless felt uncomfortable with. Equally, he didn’t want to have to justify the changes to the many authors who’d read and commented on the original versions of the stories—Donald Hall, for example, and Richard Ford and Tobias Wolff. “How can I explain to these fellows when I see them, as I will see them, what happened to the story in the meantime, after its book publication?” he wrote.

So we might question the sincerity of the letter written by Carver a week later, in which he claimed to be “thrilled” with the book that Lish was insisting on publishing without compromise in its edited form. In fact, later in the same letter Carver again asked that several of the lost pages be reinstated, but his tone suggests that by then he was either coming round to the edits or, more likely, was tired of arguing with Lish: “please look at the suggestions I’ve penciled in and entertain those suggestions seriously, even if finally you decide otherwise”.

In the end, Lish published the book as planned, the lost pages lost. Nevertheless, when it hit the shelves, Carver wouldn’t have to justify a thing to those who’d read the earlier version; the collection, surely one of the best ever published, was explanation enough. The slim, 130-page book, brilliantly retitled What We Talk About When We Talk About Love, would win almost universal acclaim. It wasn’t long before the now ubiquitous term “Carveresque” would enter the lexicon. Like his contemporary, Donald Barthelme, Carver had created a world and a style distinctly his own—except it wasn’t just his; it was his editor’s too. Naturally, success dampened his discomfort with the editorial changes, and in an interview with the Paris Review three years later he said of Lish, “He’s a good editor. Maybe he’s a great editor.”

Still, the ambivalence here is surprising. Thirty years on, the original, unedited typescript is in print under its original name, published by Vintage, and for the first time we can confirm what most already suspected: that Lish was not just a good, but great, editor. While it’s hard to agree that the original simply “isn’t very good”, as the New York Review of Books claimed, it is evident that even Lish’s lightest touches—an extra paragraph break, for instance—could be inspired and transforming. Without Lish’s edits, one of the best works of twentieth-century American fiction might have remained just another promising collection, possibly out of print by now.

Authors today tend to have an amiably professional relationship with their editor. They’ll likely be asked to do little more than delete repetitions, anglicise phrases and alter consistency errors; at the most, there’ll be a vague request to “tighten up” certain passages, whatever that means. Rarely are manuscripts rewritten or extensively cut, as Carver’s was, so close to publication. Increasingly, editors refuse to commission anything that needs significant editorial work. As former Chatto and Windus editor Rebecca Carter has said, in the world of corporate publishing, marketing campaigns take priority over manuscripts, and understaffed editorial departments have little time for nurturing talent. It is little surprise, really, that Carter became a literary agent last year.

Changes like those made by Lish are today made before any rights are sold, usually at the request of the author’s closest ally. If editors are becoming increasingly distanced from both author and text, the agent is ever more involved: Jonny Geller, who is arguably London’s most successful agent, has talked of entire mornings spent copyediting (here’s his manifesto for the modern literary agent). Even if the cliché that agents are failed editors isn’t true, this should not be happening. Edits made during breaks from selling rights and negotiating contracts are unlikely to do a manuscript justice; however pushed for time, editors need to spend more time editing. Of course, some editors today must believe, as Victor Gollancz famously did, that a hands-off approach is preferable, but I suspect most just lack the time and the courage to be radical. We should not forget that Carver was a short-story writer, and that this is a form which has always demanded condensed prose shorn of elaboration. But novelists, too, can benefit from extensive, even drastic, cuts.

David Foster Wallace often talked of his battle to avoid what he called the “look-at-me-please-love-me-I-hate-you syndrome”, by which he meant the compulsion to show off in a bid to win the reader’s admiration. If gaining the love of the reader becomes the writer’s primary aim, he begins to detest that reader for the power they have over him, as they can chose to like him or not. Sidetracked by creating showy, elaborate sentences, the writer will soon forget the ultimate purpose of the work: to communicate with the reader, not to win her love. This illuminates the complaint, once so commonly voiced by authors, that editors would pull from a manuscript all those sections the writer was most fond of.

That is not to say that every work should be edited into spare, Carveresque prose—difficulty and verbosity has its place, not least in Wallace’s own fiction—but the editor has a vital role in making sure that literature does its job: that it not only entertains but enriches the lives of its readers, and that a book or short story is the very best it can be. The poet T. S. Eliot once said that “an editor should tell the author his writing is better than it is.” Editors today should not ignore his qualification: “Not a lot better, a little better.”

You can compare here the original draft of “Beginners” with the final version of the story, retitled “What We Talk About When We Talk About Love”.

About Sam Humphrey

Sam Humphrey has an MA in Modern and Contemporary Literature from Birkbeck College, University of London. He has worked at Sheil Land Associates literary agency for four years and has a keen interest in publishing history. He is active in debates surrounding publishing in the digital age and contributes to The Bookseller's FutureBook blog. He lives in Dalston, north-east London.