You have no items in your cart. Want to get some nice things?

Go shopping

The commonest complaint that writers make is that there isn’t enough time in the day. It’s true, of course, there isn’t. Once you’ve accounted for the day job, recovering from the day job, child-care, emptying and refilling the dishwasher, sorting out the household admin and so on, there is very little, if any, time left. So how on earth does one write that novel at all without the patron, the high-earning partner, the trust fund or moving back into Mum’s and Dad’s spare room?

I’ve recently finished the first draft of my second novel. It’s a story that gestated for some time in my head before I could engineer the circumstances that allowed me to write it. I knew instinctively that I was going to need a several month stretch in which I could fully immerse myself in a new fictional world. I knew I wouldn’t be able to create the book I wanted in fragments of time squeezed between other commitments. As the parent of a primary-schooler and the sole earner in our household, resigning from work altogether was simply not an option. Navigating a few months without salary was one thing but, as someone whose job had over the years become increasingly specialised, the possibility of not finding work again afterwards was terrifying.

I decided to ask my employer for a sabbatical. It took five months of negotiation to finalise the details. This negotiation required me to recognise the needs of my workplace and do my bit to help address them so that the impact on our service would be minimal. I waited until staffing issues were sorted, until new team members were fully up and running and I agreed to stay on the on-call rota. Yes, I was impatient. Already there were ideas buzzing round in my head that I was anxious to explore on the page. But the wait was worth it for several reasons. One is that I had a chance to prepare fully so that when I finally started writing I hit the ground running. The other was that I had my employer on side so that my job was preserved for me to return to, which took the fear and risk out of the enterprise.

I planned ahead carefully for the time when my salary would disappear. I was determined that I was not going to sacrifice my daughter’s interests for my own. If she was going to be required to do some extra sessions at after school club to free up a few more hours writing time, then so be it. But I was determined that the activities she enjoyed and valued, such as her music and swimming lessons and her big cat World Wildlife Fund adoptions, were all to continue and I was simply going to have to ring-fence the money for them. So the cuts had to be made elsewhere. In other words, in my own life. I cancelled all inessential subscriptions and memberships. I re-mortgaged. I changed my broadband provider, investigated swapping utilities and credit cards. I went through months’ worth of household accounts and bank statements to shave expenses down to the essentials. Social outings before and during my sabbatical became a seafront walk and coffee out of a thermos rather than a girls’ night out at a restaurant. I walked rather than drove. I stockpiled childcare vouchers in advance so that after school club fees would be covered later. I saved annual leave so that the first few weeks of my sabbatical would be slightly better paid.

Not all the preparation was financial. I slogged through a year’s worth of CPD in just over six months so that the annual appraisal which was scheduled to fall during my sabbatical period would not turn into a major distraction. I planned my research trip down to the minutiae. I compiled a bibliography from online library catalogues. I contacted libraries early to get membership forms. I reserved materials so they would be ready for collection the minute I first stepped through the door. I was organised.

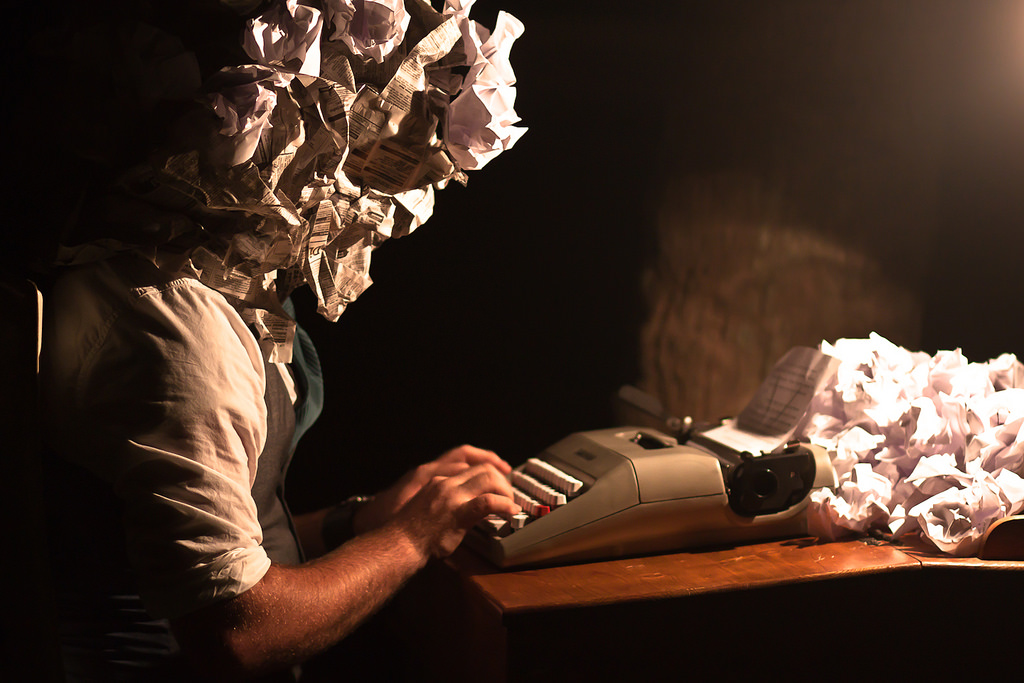

There is a view of writers and artists as chaotic, impractical, impulsive creatures who function best in the ether of ideas without the need to taint themselves with mundane, material considerations. It’s a view that writers often share of themselves. There is, I suspect, a grain of truth in it. In as much as there is a link between spontaneity and creativity. But, if generating ideas requires a certain restlessness of mind, manifesting them takes clarity and diligence. Of the writers I know, the successful ones (by which I mean those that complete projects rather than have private jets) are the disciplined ones who give a nod to practicality even if it’s not their superpower.

I realise now how unhelpful it has been to think of time as a luxury. It’s much more useful to think of it as a commodity. Money and time are intimately related in that one is usually traded for the latter. So one of the key means to free up time is to minimise financial outgoings. The less you need to earn to keep your lifestyle afloat, the less time you will need to spend doing the day job, the more time there will be to write. That said, I knew tightening the belt wasn’t going to be sufficient of itself. I would never have finished the project if I hadn’t been awarded a grant from Arts Council England. There are a few grant bodies that will fund research costs for writers and/or time to write and it’s worth investigating whether your project might be eligible. Only a minority of applications are successful. So how do you maximise the chances that yours will be one of them?

Sarah Palmer, of West Sussex Writers, writes grant bids as part of her day job. She says, ‘Read the application guidelines carefully. Some funding bodies provide very useful, detailed guidelines which will help you to focus your application, ensuring that you only give information that’s needed. Don’t just think about yourself when completing your application, but consider what you bring to the funding body you’re applying to. What are the funder’s stated aims, and how would your project help achieve them? Will your project raise the funder’s profile in the areas they are particularly interested in? If you’re applying to a regional or single-interest body, think about the relevant cultural landscape, and how you or your project will contribute to it. Go for facts, rather than hyperbole. Research your budget forecasts thoroughly, particularly if you know those funds are ‘restricted’ by which I mean that they are only awarded for a specific purpose such as travel. If you can, talk to people who have successfully applied for grants from the funder you’re applying to. Looking at successful applications will help you set the tone, and may also give you an understanding of the kind of language that particular funder looks for.’

To Palmer’s advice I would add that it is always worth getting someone else to proof-read your application before you submit, to check for concision and clarity. I have found that the process of filling out grant forms, of having to justify what you want and why, frequently helps to bring the project into focus.

Once you’ve freed up the time to write, start and don’t look back. No returning to tweak that first chapter. Develop tunnel-vision. It helps to have a dedicated work space so that you can leave your work out without having to tidy it away. I find that if work is left ‘mid-process’, it becomes easier to re-enter it the following day.

The last word should probably go to Lao Tzu: A journey of a thousand miles begins with a single step!

About Niyati Keni

Niyati Keni’s first novel, Esperanza Street, was released by indie literary press, Andotherstories, in February 2015. Described by Kirkus Reviews as a ‘luminous, revelatory study on the connection between person and place’, Esperanza Street is set in a small-town community in pre-EDSA revolution Philippines. Keni studied medicine in London and still practices part-time as a physician. She has travelled extensively within Asia. She graduated with distinction from the MA Writing at Sheffield Hallam University in 2007. She is now based in the south east of England where she is working on her second novel.

![th[8]](https://www.litromagazine.com/wp-content/uploads/2016/03/th8-300x240.jpg)