You have no items in your cart. Want to get some nice things?

Go shoppingI bought a new diary today. One of my New Year’s resolutions, probably like thousands of other people across the country, was to get into the discipline of writing a journal.

The last time I kept a regular diary was 1988, and looking back I’m not entirely sure I’m cut out to be a diarist. My entries back then, complete with creative spelling, ranged over exciting life events, (“30th December – Played Blockbusters. Had bath as planned.”), big decisions (“28th December – Have dicided not to join army but build my own rocket with my own team of astronaughts and land on mars! I will spend my 13 pounds on new mouse and cage.”) and teen trauma (“24th July – My mice killed each other, 2 dead, 1 shocked, 1 injered and 2 fine. Inbred. Had scones, jam and cream for tea.”)

I was a year older than Anne Frank when she started her diary when I penned those moving entries; it doesn’t bode well.

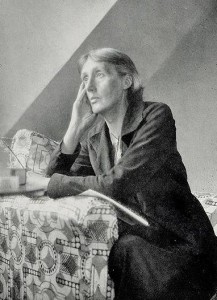

As fiction writers, we’re told diaries can help us store and sort ideas that can be used later to form stories. That’s what Virginia Woolf wanted to get out of it, at least. “The habit of writing for my eye only is good practice,” she wrote in her journal. “It loosens the ligaments.” Her ambition was for her diary to “resemble some deep old desk or capacious hold-all in which one flings a mess of odds and ends without looking them through. I should like to come back after a year or two and find that the collection had sorted itself and refined itself and coalesced.”

Sounds great, Virginia, but 22 years distance hasn’t sorted or refined my musings about inbred mice and astronauts into anything approaching memoir quality, and I’m not sure it’s going to start working now.

Doris Lessing was also dismissive, not about writing a diary (which she did) but about why anyone would want to read it afterwards. “I wonder”, she wrote, “Does the private life really matter? Who cares what is known about you and what isn’t?”

Forcing yourself to record your daily life usually shows up how unworthy of recording your daily life actually is. The early-18th Century essayist Joseph Addison made the same point about the ordinariness of most of our lives; in one of his essays he gives extracts from the diary of an “honest man… of greater consequence in his own thoughts than in the eye of the world.” This honest man’s entries aren’t far off my own 80s daily concerns: “Monday, eight o’clock. I put on my clothes, and walked into the parlour. Nine o’clock, ditto. Tied my knee-strings and washed my hands.”

Addison recommends his readers keep a diary of daily activity – not for literary inspiration, but because “This kind of self-examination would give them a true state of themselves, and incline them to consider seriously what they are about.” What he means is, it’ll make your realise how much time you’re wasting.

But sometimes even a mundane diary can deliver up sharp emotion or insight. My grandmother’s diaries were found after her death and read only once. They were all small Boots own-brand volumes, and her entries were short, mostly records of what she’d done. They were of no interest to anyone, perhaps not even to those of us who’d known and loved her. She wasn’t a writer. But then, towards the end, she began to record her feelings about my mum’s (her youngest daughter’s) death from breast cancer at the age of 48. Her words, still simple, were so harrowing that we put the diaries away again, back in their shoebox, unfinished. They’ll be of interest to some future generation of my family, but to us they were unreadable.

The natural first person narrative of a diary has the potential to mainline you straight into the author’s psyche, which is all the more shocking in amongst the dreary detail. Perhaps that’s why diaries have so often formed the structure of great works of literature – from Bram Stoker’s Dracula to William Boyd’s Any Human Heart.

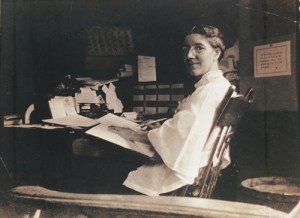

It’s a form that’s rarer in short stories, but it can be still used to great effect, as in one of my favourites, The Yellow Wallpaper by Charlotte Perkins Gillman, which is not only written as a series of journal entries, but has as one of its themes the process of diary-writing itself.

The female protagonist is banned from writing her journal by her husband (who is also her doctor), for fear it is feeding her “slight hysterical tendency,” which he believes is made worse by her “imaginative power and habit of storymaking.” Confined to her room, possibly suffering from post-natal depression, desperate to “relieve the press of ideas”, she writes in secret, but with no external experiences to record, she is left recording the walls around her – the horrendous yellow wallpaper which starts to obsess her.

Suppressing the urge to write and descending slowly into mental illness, she can’t even describe the pattern on the wallpaper coherently. She starts to see women imprisoned behind the pattern, creeping women who come out at night. In the end, she believes herself to be trapped inside the pattern.

The final chilling entry in her journal, which leaves us with the image of her crawling round the edge of the room, over the unconscious body of her husband, who has fainted in her way, is as horrible as the end of any ghost story.

Charlotte Perkins Gillman had herself suffered from depression, and she records in her own journal that she had been instructed by a doctor to “never touch pen, brush or pencil as long as you live”. The Yellow Wallpaper is a warning against following such advice, and a criticism of 19th century doctors who believed creativity fed female hysteria. Writing a journal, being able to describe and interpret your own life, was to Gillman essential, a healing work, a kind of therapy, a vent for emotion and expression of personality. She said later that not writing regularly had brought her close to “utter mental ruin”.

I suspect my diary is more likely to resemble the record of Addison’s terribly dull honourable man than Virginia Woolf’s deep old desk or Charlotte Perkins Gillman’s expression of the self.

Of course, I haven’t actually written anything in it since I bought it… I’ve been writing this blog instead. These days blogs, forums, Facebook, Twitter and the rest are making us obsessive self-recorders, better diarists than ever before. Joseph Addison’s honest gentleman’s diary does read suspiciously like a Twitter feed…

About Emily Cleaver

Emily Cleaver is Litro's Online Editor. She is passionate about short stories and writes, reads and reviews them. Her own stories have been published in the London Lies anthology from Arachne Press, Paraxis, .Cent, The Mechanics’ Institute Review, One Eye Grey, and Smoke magazines, performed to audiences at Liars League, Stand Up Tragedy, WritLOUD, Tales of the Decongested and Spark London and broadcasted on Resonance FM and Pagan Radio. As a former manager of one of London’s oldest second-hand bookshops, she also blogs about old and obscure books. You can read her tiny true dramas about working in a secondhand bookshop at smallplays.com and see more of her writing at emilycleaver.net.