You have no items in your cart. Want to get some nice things?

Go shopping

These days there seems to be a literary prize for everything. Having an argument with another author? Start your own literary prize. Don’t like one prize’s shortlist? Start your own. Are you a company who wants to show there’s a heart beating under that cold hard business exterior of yours? You know the drill.

I’m not particularly bothered by this. To me, the fact that people care enough about books to argue about them is great, and it’s wonderful to be able to acknowledge good writers from all across the enormous spectrum of reading material that we as a nation consume. But I have to admit that although I’m in favour of recognition of real talent, there’s one particular literary prize that has stolen my heart – and it’s one, perversely, that’s not about good writing at all. Praise is all very well, but sometimes writers are sorely in need of some well-timed ego deflation, and the Bad Sex Award, in magnificent style, does just that.

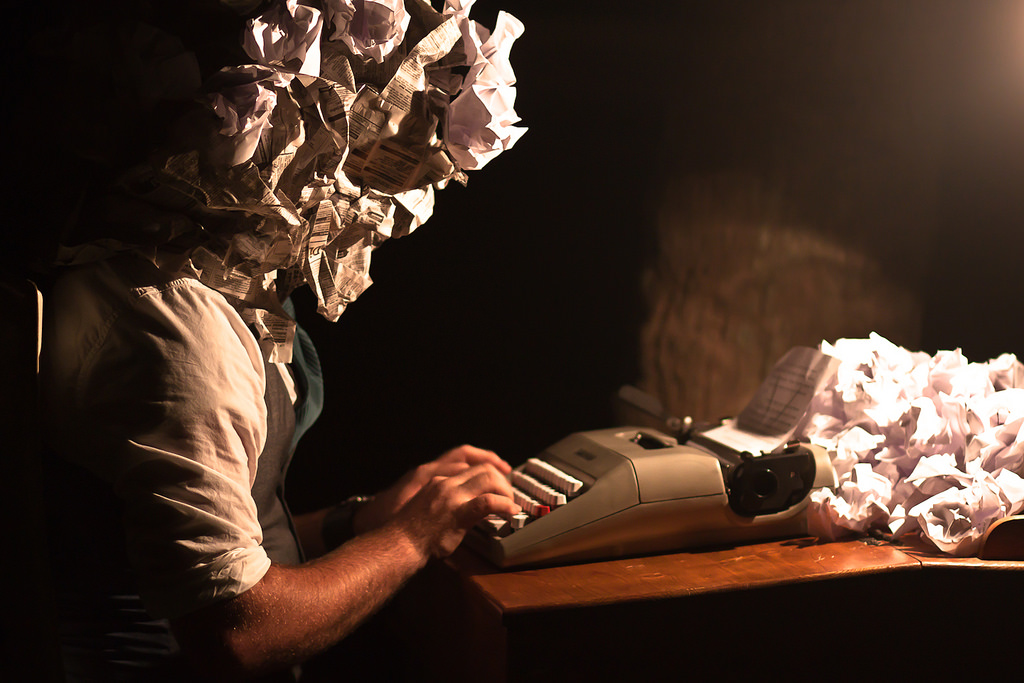

2011’s shortlist was finally announced last week, and it brings together everything I cherish about bad writing: flowery prose, overblown descriptions and metaphors that most certainly do not give the effect that was originally intended. Sad as I am to see that the particular horse I was backing – A. L. Kennedy’s The Blue Book, a true masterpiece of overegged, over-emotionalised and gruesomely over-described sexual encounters – didn’t make it beyond the longlist, a lot of magnificent material did.

This year, the deathless prose on offer includes: “He began yet another eternity of regional body worship”, “I opened my mouth wide and bit into her thigh and I did not hear her squeal”, and “We’re the same organism: some outrageous sea creature”. (Extracts from David Guterson, repeat offender Christos Tsiolkias and Dori Ostermiller respectively). It’s all jaw-droppingly, rib-achingly terrible, and it powerfully reinforces my theory that sex is the one thing that it’s almost impossible to write well about.

Part of it, of course, is the country we live in. Britain is the land of innuendo after all, the nudge nudge wink wink capital of the world and so there is always going to be something in us that needs to giggle at any mention of how’s-your-father. Here, even writing about writing about sex is fraught with difficulties. In that last paragraph I typed the word ‘roughly’ and was then racked with horrible doubt. Suddenly ‘roughly’ stopped meaning approximately and became something you might find in a Daily Mail headline describing a politician’s extra-curricular rompfest.

But there’s more to it than English prudery. Words, when it comes to sex, are so loaded down with association that they become completely unwieldy. When it comes to describing acts of a sexual nature, there isn’t a register in the world that isn’t bound up in entirely un-erotic connotations. Use clinical terms and you begin to sound like you’ve inhaled Gray’s Anatomy; use metaphors and your readers will start to wonder when they wandered into a greenhouse or a larder; use slang and you might be unfortunately mistaken for a 12 year old boy.

And that’s just the words. Sex, whether we talk about it openly or not, has so many emotions associated with it that it’s incredibly difficult not to have a sex scene turn into a festival of alarming cliché. Authors seem to assume either that sex is something so emotionally important that it can only be described as some sort of ultra-serious pseudo-religious epiphany, with ecstatic descriptions of flying and swimming and turning into plant life (and usually all at once), or as a horrific squelchy farce, all wobbling and wincing and noises.

It almost gets worse when writers try to give their sex scene the personal touch. There are many universals when it comes to sex, but what’s certainly not universal is individual preference. This is something that many authors unfortunately fail to realise. Far too often I’ve read a sex scene and been left with the distinctly uncomfortable feeling that I now know what Salman Rushdie or Martin Amis is like in bed. Call me crazy, but I’m not sure that this is knowledge I need.

All the same, though, and for all my griping, I prefer to live in a world with too much bad sex writing than none at all. There’s something very heartening in the Bad Sex Award’s assumption that the average reader’s response to, say, a graphically-described sex scene between two men will be gentle amusement at the author’s awkward choice of metaphor. Not so long ago a more pressing concern would have been when the case was scheduled to come up at the Old Bailey.

Sex has had to quite literally fight its way into literature via a series of astonishingly unpleasant obscenity trials. The one that started it all, of course, was Oscar Wilde’s in 1895, when The Picture of Dorian Grey (which, ironically, does not contain any sex scenes at all) was used to demonstrate its author’s general depravity and particular fondness for Greek sculpture. Most readers have also heard of the trial that pretty much finished British obscenity laws off. Lady Chatterley’s Lover (which more than makes up for Dorian’s lack of sexual content) was first published in 1928 and banned in Britain until 1960, when it spectacularly won its trial, allowing us all to read about Mellors’s pale, scrawny thighs without fear of prosecution. Lawrence, were he writing today, would certainly earn himself a Bad Sex Award or five.

But between those two, in 1927, there was another trial that sums up, for me, the tragedy of literary censorship. It also, ironically, contains what I think is one of the cleverest sex scenes in modern literature, an example of how you can write about sex in a way that’s both sensitive and suggestive, leaving the perfect gap for the reader’s mind (the dirtiest thing in the world) to fill in with whatever it fancies.

The Well of Loneliness, by Radclyffe Hall, is about lesbians. This is fairly obvious. The main character is a woman who has a relationship with another woman. But all the same, The Well of Loneliness is about as graphic as a shopping list. The book contains one sex scene, the scene for which it was charged and found guilty, and in its entirety it reads:

“And that night, they were not divided.”

Grim as the sexual extracts from the books on this year’s Bad Sex Award shortlist are (and they are grim), I think I prefer to live in an age where Haruki Murakami can describe a nipple as “like a vine’s new tendrils seeking sunlight”, rather than one in which seven words, with not a single genital among them, can get a book banned for obscenity. Because I don’t think sex is something adults need to be protected from, and also because that nipple description is incredibly funny.

Robin Stevens

About Robin Stevens

Robin started out writing literary features for Litro and joined the team in November 2012. She is from Oxford by way of California, and she recently completed an English Literature MA at King's College, London. Her dissertation was on crime fiction, so she can now officially refer to herself as an expert in murder (she's not sure whether she should be proud of that). Robin reviews books for The Bookbag and on her own personal blog, redbreastedbird.blogspot.co.uk. She also writes children's novels. Luckily, she believes that you can never have too many books in your life.