You have no items in your cart. Want to get some nice things?

Go shopping

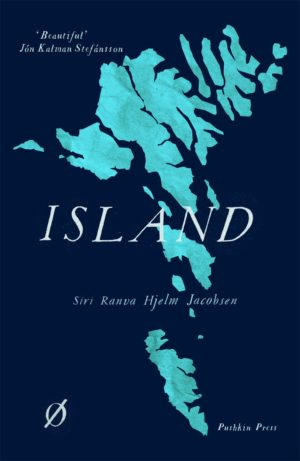

Siri Ranva Hjelm Jacobsen was born in 1980 into a Faroese-Danish family. She lives in Copenhagen and works as an author and critic. Island is her critically acclaimed and internationally award-winning debut novel, which has been translated into five languages.

Split across three generations of one family, ittells the story an unnamed Danish narrator’s return to the Faroe Islands, where she has never lived but always considered home. During her stay, she finds her stories entwining with those of her parents and grandparents as she searches for a way to reconnect with her roots.

KW: Thank you so much for speaking to us. I just wanted to say how much I enjoyed the book. I read it in one sitting, which is rare for me.

SRHJ: I’m glad to hear that.

KW: Let’s get started with a perhaps deceptively simple question. What inspired you to write Island?

SRHJ: I wrote the book during a time at which a certain ethnically focused populist nationalism was very much on the rise in Denmark, which made the question of what it means to be Danish very present in society. As a person who has family scattered all over the world and as a person who doesn’t look very Danish, it is a question that has always been posed of me – “Oh, you’re not all Danish, are you?”

It’s a question of what it means to belong and have a home and how these basic human needs are connected to nationality. Although it’s an interesting thing to talk about, you start to experience a certain distance between yourself and what you’re supposed to be when you’re asked this question your entire life.

Having roots in other places in the world, I have experienced a very strange longing for home. It was this core feeling that I wanted to explore.

KW: When you’re writing a book with obvious parallels to your own life, there’ll inevitably be a suggestion that it’s autobiographical. How much of Island, if any, is autobiographical?

SRHJ: Not very much. My grandmother never had an abortion on a ferry, and my mother’s great aunt never turned into a seagull. Although I wouldn’t call it autobiographical, I do I share a lot of feelings with the narrator, and it’s been very interesting for me to explore them outside of myself.

KW: How similar are you to the book’s narrator who is only referred to as the granddaughter?

SRHJ: Not at all. I’m a very inquisitive person; if I don’t understand something, I confront it, but I needed a narrator with a different mindset. The granddaughter is very nonconfrontational; a little withdrawn and has a very soft imagination. Instead of going to her relatives and asking about her family’s history, she tiptoes through their stories and then fills in the gaps with her own poetic imaginings.

KW: There is a s sense in the book that, as we mature, we develop a more rounded understanding of our older relatives. Did writing the book help you see your own parents and grandparents differently?

SRHJ: It’s a funny story. When the book came out, I took part in a literary festival for debuting novelists and scholars from across Europe, featuring one novelist from each European country.

During the festival, the scholars discovered two common themes: One was migration and its consequences in relation related to identity. The other was grandparents, which really surprised the scholars; they’d never previously seen grandparents as a hot topic for young people.

The world is moving so fast that my generation – and those younger than me – don’t have an immediate connection to the generations before us. Our lives are radically different from those of our grandparents and our histories are, sort of, severed. This leaves a real gap as knowing your history, knowing your roots, and having a connection backward in time are necessary for a stable and strong identity.

When I was in my early 20s, I interviewed my grandfather. It was hard for him to tell his story. It wasn’t a particularly dramatic or strange story, but he was a proud man and relaying your life is always difficult. I’m very glad I did it.

KW: I think that’s true for everyone. We expect our grandparents to be quite conventional and just envision them as older people. Until we’re older ourselves, we don’t realise that they were young too and they had messy lives as well.

SRHJ: Exactly. It was very important for me that the grandparents of Island didn’t have a particularly spectacular story. I wanted their story to be relatable to most people who have moved from one place in the world to another – although that choice, in itself, can be very dramatic.

KW: In the book you juxtapose some really bleak images with almost fairy-tale-like descriptions of the landscape. One that really stood out for me was the description of the protagonist’s grandmother having an abortion and it being like a crow pecking at her urethra. You can almost feel that. How do you come up with these images?

SRHJ: I’m glad that was so memorable, but also, I’m sorry! There is a children’s song called “Krákan” which has always fascinated me and involves a crow. It has little cute melody, but the words are quite terrifying. If you’ve ever seen a crow pecking, you’ll know that they make these extremely precise little motions, but that their movements are also quite fast and erratic.

My first great literary love as an adult was the Swedish author Selma Lagerlöf, who was the first female Nobel Prize winner for literature. She wrote realistic stories but also had a very gothic streak. What she did that I found so fascinating was that she used nature to describe the characters’ inner lives. For me, that was a very helpful strategy for this narrator who’s kind of shy.

When it comes to the abortion, the first contractions are very bad, but the narrator is also trying to protect the modesty of this person who, at the same time, is completely laid bare, so she goes to nature and natural imagery. I think, as humans, we can accept a lot of violence in nature.

KW: The next thing I wanted to ask you about was translation. As a native English speaker, I absolutely loved the translation, but how do you feel about having your work translated?

SRHJ: I’m very happy that you like the translation. I’ve been working as a literary translator for the past six years myself. I’m very grateful that I’ve had the opportunity to do that because it has taught me a lot about being translated.

Being translated is amazing but also very difficult, especially if it’s into a language you’re familiar with yourself. For example, being translated into English, for me, was very different from being translated into Italian as I don’t understand a word of Italian.

There’s also a real learning experience, and you learn so much about yourself as an author that only a translator can teach you.

KW: Island is obviously focused very much on a specific part of the world. But the themes of identity and place really resonated with me in the UK. Did you expect the book to be so relevant for people wherever they are in the world?

SRHJ: I hoped. I didn’t really know what to expect from my first novel, but I’ve had some amazing reactions on a very broad spectrum. For example, I’ve had the daughter of Iranian refugees tell me she really related to the book. Then, at the other end of the spectrum, there was the loveliest old man who had his son teach him how to use Facebook Messenger so he could write to me and tell me that every summer when the forests in Sweden turned green, he longed for his grandmother’s old cottage.

It has been such a privilege. When I close my eyes, I can see a map of the world; the reactions are like lights connecting in a web. I do think that the themes of the book, especially migration and belonging, are basic human themes, which will become increasingly important as we begin to move around more and more.

KW: I’ve read that you have an interest in ecofeminism. I think the cause is very misunderstood, or it certainly is in the UK. A lot of people see it as being anti-men or being for hippies. Do you have any thoughts on that?

SRHJ: It’s so funny because I recently attended a literature festival in Italy and took part in a panel discussion on climate fiction. I think that’s an iffy term, but it’s fiction dealing with the changes in nature that are occurring globally. A young Italian woman raised her hand and said that every time she took part in any form of activism, politicians would dismiss her as a hippie feminist.

It’s been the same all over the world, but it is changing in Scandinavia now. It’s becoming too difficult to write these movements off as having nothing to do with mainstream culture.We all have to figure out how to live in the world, in the best possible way, as it changes. These changes are going to happen and it’s going to affect us globally, although the effect will be worse for some than others.

If we want to keep our humanity and, if we want to sustain our democracies, these are questions we must concern ourselves with. It starts with the economy, with redistributing resources and wealth in a way that is sustainable. I’m not an economist, and that’s not my area of expertise. The small contribution I can make is tell stories and ask questions, through literature, that invite people to imagine new ways of being.

KW: For me, the book very much fell into the genres of life writing and nature writing. These are two of my favourite genres. What do you enjoy reading yourself?

SRHJ: My personal tastes in literature are a little different. I’m a great lover of science fiction, but I think that, even in the in the strangest stories, what catches you is the basic humanity.

After my literature degree, I still have a list of required reading on the backburner, which is growing all the time. I think it’s a magical state of being; to be constantly aware that the world is full of art, experiences, and stories; that there are so many that you will never get through them.

KW: That seems like a perfect way to end. Thank you again for speaking to us.

SRHJ: My pleasure.

About Katy Ward

Katy Ward is a short story writer and journalist based in the north of England. Her fiction, which has been published in various journals in the UK and US, focuses on the themes of addiction, social class, and shattered relationships. As a journalist and editor, her work has appeared in numerous national newspapers and independent media outlets.