You have no items in your cart. Want to get some nice things?

Go shopping

Even if our predecessors had started from land with inadequate supplies, they would have managed well enough as long as they drifted across the sea with the current, in which fish abounded. There was not a day on our whole voyage on which fish were not swimming round the raft and could not easily be caught. Scarcely a day passed without flying fish, at any rate, coming on board of their own accord. It even happened that large bonitos, delicious eating, swam on board with the masses of water that came from astern and lay kicking on the raft when the water had vanished down between the logs as a sieve. To starve to death was impossible.

The old natives knew well the device which many ship-wrecked men hit upon during the war chewing thirst-quenching moisture out of raw fish. One can also press the juices out by twisting pieces of fish in a cloth, or, if the fish is large, it is a fairly simple matter to cut holes in its side, which soon become filled with ooze from the fish’s lymphatic glands. It does not taste good if one has anything better to drink, but the percentage of salt is so low that one’s thirst is quenched.

The necessity for drinking water was greatly reduced if we bathed regularly and lay down wet in the shady cabin. If a shark was patrolling majestically round about us and preventing a real plunge from the side of the raft, one had only to lie down on the logs aft and get a good grip of the ropes with one’s fingers and tots. Then we got several bathfuls of crystal-clear Pacific pouring over us every few seconds.

When tormented by thirst in a hot climate, one generally assumes that the body needs water, and this may often lead to immoderate inroads on the water ration without any benefit whatever. On really hot days in the tropics you can pour tepid water down your throat till you taste it at the back of your mouth, and you are just as thirsty. It is not liquid the body needs then, but, curiously enough, salt. The special rations we had on board included salt tablets to be taken regularly on particularly hot days, because perspiration drains the body of salt. We experienced days like this when the wind had died away and the sun blazed down on the raft without mercy. Our water ration could be ladled into us till it squelched in our stomachs, but our throats malignantly demanded much more. On such days we added from 20 to 40 per cent of bitter, salt sea water to our fresh-water ration and found, to our surprise, that this brackish water quenched our thirst. We had the taste of sea water in our mouths for a long time afterward but never felt unwell, and moreover we had our water ration considerably increased.

One morning, as we sat at breakfast, an unexpected sea splashed into our gruel and taught us quite gratuitously that the taste of oats removed the greater part of the sickening taste of sea water!

The old Polynesians had preserved some curious traditions, according to which their earliest forefathers, when they came sailing across the sea, had with them leaves of a certain plant which they chewed, with the result that their thirst disappeared. Another effect of the plant was that in an emergency they could drink sea water without being sick. No such plants grew in the South Sea islands; they must, therefore, have originated in their ancestors’ homeland. The Polynesian historians repeated these statements so often that modern scientists investigated the matter and came to the conclusion that the only known plant with such an effect was the coca plant, which grew only in Peru. And in prehistoric Peru this very coca plant, which contains cocaine, was regularly used both by the Incas and by their vanished forerunners, as is shown by discoveries in pre-Inca graves. On exhausting mountain journeys and sea voyages they took with them piles of these leaves and chewed them for days on end to remove the feelings of thirst and weariness. And over a fairly short period the chewing of coca leaves will even allow one to drink sea water with a certain immunity.

We did not test coca leaves on board the Kon-Tiki, but we had on the foredeck large wicker baskets full of other plants, some of which had left a deeper imprint on the South Sea islands. The baskets stood lashed fast in the lee of the cabin wall, and as time passed yellow shoots and green leaves of potatoes and coconuts shot up higher and higher from the wickerwork. It was like a little tropical garden on board the wooden raft.

This is an extract from Kon-Tiki Across the Pacific by Raft (1950). Full text available from the Universal Library.

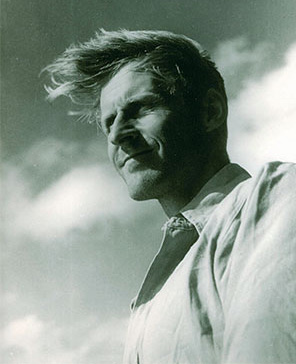

Thor Heyerdahl (1914-2002) was a Norwegian ethnographer and adventurer with a background in zoology and geography. Heyerdahl became notable for the “Kon-Tiki expedition”, in which he sailed 8,000 km by raft from South America to the Tuamotu Islands.

Thor Heyerdahl (1914-2002) was a Norwegian ethnographer and adventurer with a background in zoology and geography. Heyerdahl became notable for the “Kon-Tiki expedition”, in which he sailed 8,000 km by raft from South America to the Tuamotu Islands.

One comment