You have no items in your cart. Want to get some nice things?

Go shopping

Mrs Billeci’s daughters had invited me round to play at their house. They lived on the floor below me and always ignored me. There were two years between them but they looked like twins and I could never tell them apart. They had long hair slicked back with hairbands, and black eyebrows. The contrast between the platinum-blond hair and the black eyebrows was extreme. I was sure their hair was dyed like mine; I had used Cristal Soleil blonding spray and I was all eyebrows too. But when I discovered it was their natural hair colour because their great grandparents were Swedish – platinum-blond Swedes – I felt put out. My relatives were all from Palermo: the women were housewives and the men were door-to-door salesmen for household goods. It’s been that way for generations and there’s not a lot I can do about it.[private]

The family photo that has pride of place on the living room unit shows me, my dad, my mum and my grandma, and we all look just like each other as my parents were first cousins. The Billeci sisters’ mum and dad, on the other hand, both worked for the council but they’d met at the bus stop for the number 29, which never comes.

Their house was full of rugs and bright-coloured Nino Parrucca vases and the walls were decorated with burgundy curlicue wallpaper which looked like the curtain in the Massimo Theatre. I would stroke it the way you do with velvet, running my hands over it until I’d grazed the skin. “Don’t get blood on the walls” they’d say. I’d suck my fingers and clench them into my palms behind my back.

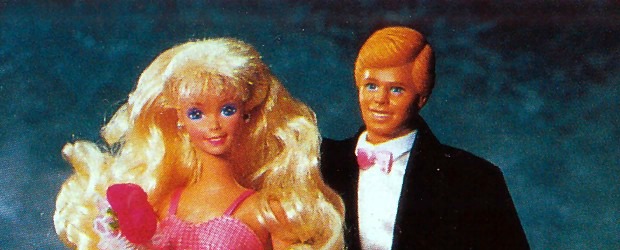

They had about fifty Barbie dolls scattered across the floor, all naked because the clothes were in the wardrobe. The action figures consisted of two handsome Kens and one hideous Big Jim who, unsurprisingly, always ended up on its own. They wanted my Barbie to pair up with him, even if my Barbie was a Tanya. My dad thought only Vikings from Northern European countries like the Swedes, or Americans who lived in big houses with swimming pools, could afford real Barbie dolls. Stumpy Sicilians with bleached hair could only hope to play with more rustic versions. And so he’d bought me Tanya, who came in a swimsuit with no accessories whatsoever.

Barbie’s wardrobe featured knickers, shoes, bags, collections by top stylists and work outfits. There was a Barbie secretary but not a Barbie waitress. Barbie the nurse but no Barbie the waitress. I knew a little bit about fashion, my mum worked in the boutique of an ailing aunt where she did everything and even I did lots too when I used to go in to help her. So to me, based on what I’d seen, waitress uniforms were always the nicest.

“Let’s play debutante balls,” the Billeci sisters had said.

“Nooo. Let’s play at Alice. I’ll be Alice and you can be the two waitresses.”

Alice was a TV program that used to be on Tele7 in the morning before school. It was set in a snack bar called ‘Mel’s place’ where the owner was a pain in the neck like my dad and the waitresses wore pink uniforms with a tiara-type cap.

As aprons we could have used Barbie ballerina’s tutu and Cicciobello’s bibs.

“They’re old. I don’t want to be old,” one of the Billeci sisters said.

“Alice was actually a singer.”

“But she’s old.”

“But she sings.”

“What’s that got to do with it?”

Art is oblivious to age, that’s what, as my dad always said when he sang Peppino di Capri songs in the living room and wanted my mum to enter him for the Corrida TV talent show. My mum was too embarrassed to enter him because he was old, tone-deaf and the audience would’ve booed him off, banging pots at him. She thought making a fool of yourself was more humiliating if you were old. Art is art, he’d say, even though when he talked about art, he was only saying it for the sake of it and he never did go on the Corrida.

I didn’t tell the Billecis this though. They said that if I wanted to be a skivvy then I could play doctors and nurses with the boys. Then they put Spring Barbie’s dress on Tanya and paired her up with hideous Big Jim and his painted-on clothes. All the couples were to do a waltz to the automatic tune played by a Bontempi keyboard that could do any musical style, even a neighing horse. Tanya’s arms didn’t bend like Barbie’s, Big Jim had to hold her up. She looked at him gratefully but his eyes gazed elsewhere. Whichever way you moved him, his pupils never looked straight at Tanya’s. I used a black pen that I kept in my pocket, just in case I got the urge to draw clothes, to make Big Jim’s pupils bigger, but ended up giving him a squint instead and he still wouldn’t look at Tanya. The Billeci sisters were adamant I’d broken their doll and they threw all three of us out: me, Tanya and Big Jim.

The next day I asked Antonio, whose mum was Mrs Gueci the lady on the sixth floor, to play at restaurants. He did catechism lessons with my mum and when his mum was working late and his dad was who knows where, he would stay at ours for dinner sometimes. I think they sent him to catechism class to keep him out of trouble. It was unusual for a thirteen-year-old not to have had his first communion by that time. I’d had mine the year before, when I was nine, the age you’re supposed to do it. Even though he’d never asked me to play doctors and nurses, he’d still pinch my calves and sometimes further up as well.

“How do you play?”

“You be the rich man who comes into the restaurant and I’ll tell you what’s on the menu.”

“And then?”

“Then you choose what dishes you’re having and give me a tip.”

I set the table on the desk with my dad’s samples: a Christmas tree table cloth, the Tweetie Pie and Sylvester plate, the Batman cup, plastic cutlery and a paper napkin. I had my maths jotter as a notebook and a black see-through hairdressing cape that I’d found in my mum’s drawer as an apron. For me, waitressing was all about the apron.

“Good afternoon sir, what can I get you?”

“What’s the dish of the day?”

“Hmmm, let’s see, baked pasta and breaded cutlets.”

“I’ll have lasagna please.”

“I’m sorry sir, but the lasagna is finished.”

“Well, take your trousers off then.”

Antonio threw me on the floor and tried to take my trousers off, which didn’t take him long as I’d already unbuttoned them after eating pasta omelette and two slices of meat. “You’ve got a fat belly” he said, tickling my stomach. No matter how much I wriggled to get away, he was twice the size of me. When my mum opened the door to my bedroom, that’s how she found us: me in my knickers and him on top of me, with the cape tickling me. She grabbed him by the ear and dragged him out.

“You and me are going to go to the doctor now. The real one,” she said.

“Miss, we were just playing,” he said.

“Playing around was what got the baker’s daughter pregnant.”

The baker’s daughter, who was the same age as Antonio, had the same Cinzia bike as me. Instinctively I looked at my stomach, all swollen from everything I’d had to eat.

“Miss, I didn’t even pull my zip down.”

“Be careful what you say,” my mum had replied, ripping the cape off him. Then she turned to me and said, “What is that napkin doing here?”

“We were playing restaurants.”

“The next time I’ll send you away to boarding school. You don’t even know how to lay knives and forks properly.”

Antonio and I avoided each other for a bit; after his first communion, he didn’t come to my house anymore. And even if I met him in the lobby waiting for the lift, I would head straight for the stairs, and if I bumped into him on the street I would start running. His being there made me feel like I was in my knickers. Until, little by little, he started pinching my calves again, and a bit further up too.

“Take your trousers off,” he’d say, but I’d refuse. “Why don’t you get the Billeci sisters to take their trousers off?” I’d ask, to wind him up. “I want to marry them”. That’s when I’d take my trousers off and wish the sisters the worst luck in the world.

I watched the baker’s daughter every day from my window to see how her tummy was growing. When she wasn’t at the baker’s she’d be on the swing in the park, just sitting there. “What is she thinking?” I’d wonder. No one knew anything about the baby’s dad. Whenever I asked my mum she just said the dad was away.

I dreamt about going to Paris to be a waitress when I left school. I imagined myself with a button nose and a bun in my hair, wiggling my hips in a little black dress and lacy apron as I swung the salt shaker to the rhythm of ‘Brigitte Bardot Bardot’. But that doesn’t mean when the teacher asked me what I wanted to do when I was big I would say “waitress”. It wasn’t that kind of dream. I wanted to be an artist but it seemed to me that I’d have to be a waitress first if I was going to be an artist. Whenever I saw celebrities interviewed on TV, they almost always said they’d started out as waitresses. I wasn’t really sure which kind of art I wanted to do, I liked drawing clothes but despite having my pen with me, the inspiration never came, and to make matters worse, my aunt had died leaving the shop to go out of business.

Big Jim and Tanya pretended to waltz together on my bedside table. She gazed ever more lovingly at him while he looked cross-eyed and distant. “I’ll find the right guy for you Tanya” I’d say. “Don’t worry.” But I’d keep forgetting to find someone for her. Time marched on while Tanya waited for someone to look at her properly, and the only thing that grew was the baker’s daughter’s son who would play football by himself in the football field while his mum would sit on the swing thinking about who knows what.

I’ve always wondered why it is that I see myself as a waitress in Paris. Alice was set in America and I’d never been to France.

Antonio thought that speaking to me in French would excite me like Gomez in the Addams Family.

“Escargots, s’il vous plait,” he would say when we played at restaurants.

“No, not snails. Have fondue instead.”

“I want the snails, ma cherie” and he’d kiss me on the arm like Gomez. He had me wear an apron of his mum’s – she worked in the hospital canteen – and a pair of hold-ups he’d pinched from his married sister. He’d kiss my arm all the way up to my neck and I’d bend over on the other side to pull them up. We didn’t even try to act out the scene with plates and cutlery anymore. He sat on the couch and I stood.

“No snails. What about vol-au-vent?” I pronounced it vollavant.

“Either you learn French or we play a different game,” Antonio said. We played a different game. It was still restaurants but in a hospital canteen instead of a French restaurant.

“But the canteen is more self-service,” I said. I was more interested in the interaction between the customer and the waitress.

“Unbutton your blouse and you’ll see some interaction.”

“Let’s do this: you pretend you’ve just woken up from a coma after ten years and I teach you how to eat a balanced diet.”

“But you only ever eat pasta omelette.”

“That’s not true.”

“Really? Well, unbutton your blouse and I’ll wake up from a coma. I’ve even lost my memory and am missing an arm.”

“OK. But just the top two buttons.”

“Feed me.”

There was nothing to feed him with but I fed him all the same.

After our first real kiss with our mouths wide open and touching teeth, I asked him if we were engaged. He said that people who are engaged have a ring.

“Can you see any rings?” he asked.

“No.”

“So there’s your answer.”

We’d meet up every now and then when he had the house to himself. We went further and further each time. At fourteen I thought I might be pregnant. I told him and he asked me if I was thick. “Do I have to explain how intercourse works?”

“I’m ten days late, I feel sick.”

I’d been told that one of my cousins had got pregnant while she was still a virgin just from touching her boyfriend with no clothes on.

“Maybe it’s hereditary,” I told Antonio. “We all look the same in my family.”

“You’re thick.”

After that we saw less and less of each other. He would say, “do like this, do like that, stop there.” He hardly touched me. One day, out of the blue, he invited me to the cinema where we sat like statues in our seats. At the end of the evening, he said that in the next few days he would take me out to dinner, to the zoo, to the fun park and to all those places where couples go. This threw me a bit because he hadn’t given me a ring, but I thought it was right to be engaged to someone that I’d seen more naked than anything else. The next day, instead of taking me to dinner, he gave me back an apron I’d left at his house and I saw him in the lift with one of the Billeci sisters who lived on the first floor and didn’t need to take the lift. I was a picture of misery when I got in the house and I couldn’t shake it. My dad, who didn’t know anything about me and Antonio, said, “these things happen.” I didn’t use the stairs or the lift for a week, I just stayed in bed with the shutters closed, agonising over which of the two Swedish sisters he’d picked, the younger one or the older one. My dad said, “Why don’t you punch him instead of just sleeping?” – which got me mad. I left the house with my fists clenched after that but I never met Antonio, and when I finally saw him, it’d been too long and I just said Hi.

One day, Big Jim and Tanya went missing. The first place I looked was the bin because my mum had been on at me to throw them away for years. Then I found out that she’d given them to a little girl at catechism classes whose house had burned down. The girl’s mum was staying with relatives for a bit, the dad with other members of the family and she was being shunted from one place to another.

“We’re hardly family,” I said to my mum. She looked at me in disgust.

While the girl was playing in the kitchen, I went in with a Cicciobello doll in a pram and asked her if she wanted to swap. Cicciobello’s face was covered in dust so I’d wiped it with a cloth.

“After the wedding,” the little girl said.

Big Jim and Tanya were getting married in the oven. Big Jim was wearing a black ribbon as a tie and Tanya the organza net from a wedding favour as a veil. He had his arm round her and despite the squint, was looking straight at her. At first I thought it was a miracle, but I hadn’t done it.

I turned to my mum who was shelling peas with my grandma and said, “I hate you.” She slapped me, not because she was hurt but because I’d said it in front of the little girl. Little girls whose houses have burned down shouldn’t have to hear the hate word.

I’d been looking for a special pen for years to make Big Jim’s pupils bigger without realizing that all I had to do was bend Tanya’s head a bit.[/private]

This story was originally published in Mari Accardi’s debut collection Il posto più strano dove mi sono innamorata (Terre di Mezzo Editore). Translated by Denise Muir.

Denise Muir is an Italian to English creative commercial translator, currently finding her feet in the literary translation world. Last year she started a blog about literary life in Italy and also writes for an online newspaper chronicling life in the Bel Paese. She is involved in the Translators in Schools program with the Stephen Spender Trust, works with an Italian library to promote reading in the community, blogged about and took part in events for the Stop Violence Against Women campaign and takes books into Italian classrooms to get young children off computers, away from TVs and into the real world.

About Mari Accardi

Mari Accardi was born in Palermo, Sicily, in 1977. She studied foreign languages and creative writing. In 2008 she won the literary competition "Subway Letteratura" and her short stories have appeared in Italian magazines and webzines, including L'accalappiacani, Watt, Doppiozero.com and Granta Italia. Her first book, Il posto più strano dove mi sono innamorata (The strangest place where I've fallen in love), is available from Terre di Mezzo Editore.