You have no items in your cart. Want to get some nice things?

Go shopping

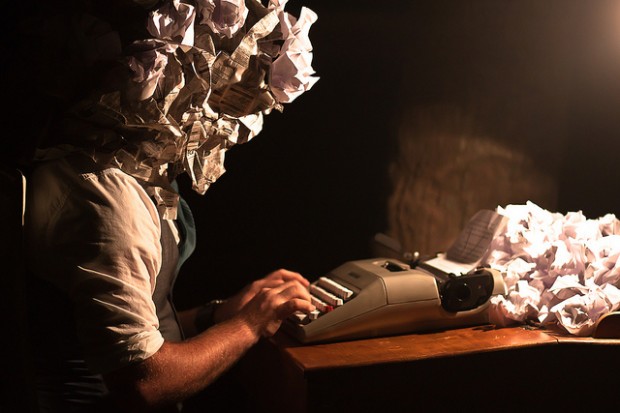

(1)

A writer is always serving sentences and is therefore always in prison.

(2)

For me, the truth and the truth alone is impossible to write, for when I try I end up writing I love you, I love you, I love you only. I’ve to manipulate. This is going to be fiction.

(3)

Consider a hollow sphere made of a hard wood called The Third World. Inside it an abyss, an abyss both created and protected by The Third World. On the surface crawls a termite. Its name is Saadat Hasan Manto. The termite bites into the wood and turns up a lot of The Third World dust, but that’s not enough; it can’t bore through to the abyss. The teeth erode with time.

But Manto carries on. He is delusional. There’s no point, but he carries on. There comes a time when he feels that he’s really close, just a little more labor and there would be a hole in The Third World, a hole that would take willing future termites into the abyss, but then the time passes and Manto tires. He is going to die. He collects all The Third World dust he has created and hurls it on The Third World. I came the closest, he says. This too is literature, he says.

(4)

I saw the word solipsistic used in a rejection email I received from an editor. It was used against me, or rather, it was used to describe the short story I’d sent to the editor for his kind consideration. I didn’t respond to this email. I didn’t know how to.

(5)

While walking on a lonely street late in the night, under the photogenic light of halogen lamps, a light that looked both poetic and doomsday-like, I was scared if what the editor had said was literally true. My toothache was the only thing that saved me from paranoia.

(6)

Extremely detailed love stories, where love is almost obsessive, when rendered in a monologue, will qualify as solipsistic. Because the only way for obsessive love to continue being obsessive is to turn unto itself, to fold over, to gaze at itself and find consolation in the return of the gaze. There is a limiting point of, and from there on nothing exists beyond the geometry of the gaze.

(7)

But where is the detail in my love story?

(8)

I’d a dream in which I saw a man in very loose, white kurta-pajama. The pajama was from another era. The man was a bit drunk. Maybe a lot drunk. Spectacles askew, hair a mess. Although you could sense that in usual times both the spectacles and the hair would be impeccable. He was walking on a road in a city that looked both ancient and familiar. He was Saadat Hasan Manto. He was smoking a cigarette, Caravan brand. He was smoking frenetically, as if all he wanted to do was inhale. It is valid to ask how I know the brand of the cigarette, for this is a dream. But in fact, I also know the brand of liquor in the pocket of his kurta, it is a quarter of Hiran brand whisky. Please note that a dream is both a cinematic and a novelistic experience.

(9)

Am I just fooling here, or is it possible to say that inner life is more broken than ever?

I don’t know, but if it is, so should be fiction.

The grand continuity of narrative is no more. All that became hyper killed it – hyper-reality, hyper-referentiality.

Even when I feel the direst isolation, the uttermost pangs of love, the most brutal betrayal, even when I’m completely inside any given emotion, I can think of many other things, many outer things. I can remember a novel that contained a situation very similar to mine, or I can think of the brand of cigarette that is least harmful to my lungs, or I can remember the issue of the internet bill that needs to be paid today for the sheer sustenance of normal life. All this comes briefly, but potently. Potently enough to push me into a perpetual state of distraction, a state that persists even in the most poignant moments of my being.

(10)

I step out of Classic Restaurant after another solitary dinner, and I go to a cigarette hatch next to it. I ask for a few cigarettes. The vendor uses the word dollar for rupees. He says something like, Give me one more dollar and I will give you ten dollars back. It’s funny, I don’t know how. I smile at him. He smiles back.

I think of happiness, of the essential conditions for it.

Is it possible to simulate happiness, to a point when the simulation ceases to matter, and happiness becomes a neurosis in itself? Is it as simply achieved as by calling a rupee a dollar?

And which word is more proper here, simulation or dissimulation?

I walk on. I walk on and others walk past me. Most of those who walk past me are men caked black by their work, most likely physical work, with their cheap, shoddily-cut shirts un-tucked and falling over their waists in a manner that is almost an insurrection against what may be called fashion. An indifferent, busy one passes, his eyes looking down to the road. Then another one: with a weird confident gait, the amplitude of his arms’ movement forcing me to adjust. I think of Dostoyevsky for a while, of the underground man’s ranting about crossing the street and always having to make way for someone coming from the opposite direction. But I know that that ranting is not apropos of my walk here. Then another man passes, a wetness glistening across his cheeks, a wetness that could be smeared tears, and all of a sudden I know beyond doubt that these are tears. The next moment there is a black hole inside my heart and it does what a black hole does even before I can identify it as horror or sadness.

My mind once again goes to the word solipsistic, and for a brief while it appears an alluring thought that there is nothing beyond me, that all these men crossing me on my walk back home are my creation.

(11)

Thinking of nausea makes you nauseous, thinking of love makes you _______

(12)

So in the dream it is morning time. My perspective has shifted from Manto. Now, there is man approaching from the other direction. Round Joycean glasses, tubercular face, jaundiced complexion, Bali cigarette dangling on the lips, thin poetry book in one hand, eyes too black to describe, thin curly hair, loose old T-shirt, dirty jeans, toe-gaping sneakers with shoelaces untied and made a grimy brown by the street, torn socks beneath, a smell of coffee and cunt in the mouth, or perhaps coffee and paper, teeth greyed by a summer of eating only fish and nothing else, long slender fingers, a folded dagger in the jeans pocket, no pens, no paper, and in the head an Italian movie’s violent scenes fighting with a French movie’s erotic ones.

This man is Roberto Bolaño, no fucking doubt.

(13)

This, here, is not a dream. This is for the man on the streets. This is for the man who is so naked he does not even have the luxury to hide his erections. This is for the man whose sweat smells of iron and bread. This is for the man who serves boiled eggs on square newspaper cuttings, the eggs garnished with onion and coriander and a salt whose saltiness is beyond measure. This is for the man who runs the risk of being swallowed by an open manhole every monsoon. This is for the man who will never ever read this. This is for the man who pedals an old bicycle on the Western Express Highway, where even the mini-whirlwind of a racing Audi can take him to the next world. This is for the man who sells idli-sambhar in the mornings and cigarettes and chai in the late nights, all by moving through residential quarters on a bicycle. This is for the man who never looks at shop windows, because for him happiness is still something that can be seen and bought. This is for the man who knows his wife sometimes grants favours for money, and whose only hope is to keep this fact in some secrecy. This is for the man who carries two heavy buckets of water for some obscure master for some obscure reason. This is for the man who scratches his balls viciously. This is for the man who thinks of a belly as a symbol of the kind of social weight he will never have. This is for the man who ridicules love, for love is never as strong an impulse as survival. This is for the man who gets bad business ideas, like selling slightly rotten tomatoes to those who want to make their own ketchup at home.

(14)

Of course I’ve seen a psychiatrist. She’s a lady in her thirties, living alone in Bandra West. She calls her subjects (or objects?) to her house. I see some irony in the fact that she’s divorced. I must say that she, with a spunky bob-cut and light colored tops and linen pants, is quite attractive. And chirpy. I’m not a psychoanalyst, she says often, I’m a psychiatrist. Or maybe she says that she is not a psychiatrist but a psychoanalyst. I don’t know. She did explain the difference between the two to me once, but I’ve forgotten. Anyhow. More than listening to my afflictions and remedying them, I sometimes fear that her agenda is to seduce me. The first time I met her, it was for jealousy. Recently, I’ve met her for loss. That I would choose jealousy over loss is not saying much. The first time I met her, she told me that if ever I was to separate from her (my love), the greater loss would be hers (my love’s). I think this was her (the psychiatrist) trying to manipulate me into health. There is really no way to convince me now that the greater loss has been hers (my love’s).

In our last session, the attractive psychiatrist told me that I’m neurotic, that I’m neurotic about my love and my writing. I wanted to correct her, because it is likely that I’m not as neurotic about my writing as I am about literature. There is a big difference there. Neurosis is not a bad thing in itself, she tells me. Everyone is neurotic, she adds. Can you tell me what she, my love, is neurotic about? I ask her. Maybe happiness, maybe she is neurotic about the abstract concept of happiness, she says. I mull over this. This seems right, so right that it makes me visibly disconcerted. To save myself I ask her, What are you neurotic about? The psychiatrist laughs. She’s really pretty when she laughs. She says, I’m neurotic about neuroses, maybe. That’s complicated, I say in a funny vein, but in truth I’m now thinking about the infinite loop of neuroses. The bad, mad infinity of it. I ask her if I need therapy, or medication. Yes, you need some help, she says. I don’t know why but I sense some malice in this statement, or maybe I sense a lie. The room constricts a bit. Is it possible to live with neurosis? I ask her. Yes, she says. But it needs to be kept in check, she adds. OK, I say, somehow disbelieving everything she has said, and then I rise from the tiny designer ottoman that I’m sitting on. I look at her, sitting on a chair with a question in her grey-black eyes. What is this question? I wonder. I don’t wait for the answer to come to me. I walk toward the door that will take me out of her living room, out of her house, out on the street. While I’m going out she asks, Will you come next Sunday? I’ll let you know, I reply. It’s nice to see you, she says. I leave.

I don’t go the next Sunday, or the next. Which is to say that now I’m living with unchecked neuroses. Of love and of literature. I walk on the street and I see unhappy men and I think many things. I think that all these men and all this unhappiness is my creation. And I think how can all this, this passing by unhappy men on Bombay’s streets, be made literature? And I think, How will someone neurotic about happiness react to all this unhappiness on the street?

Maybe she’ll just leave Bombay.

(15)

There is nothing to say, though she calls me every day, out of some vague concern she can’t comprehend and I’m too scared to guess. Sometimes she even addresses me ‘My love.’ I don’t call her because I’m scared of filling silences with piteous love.

(16)

A coitus-interruptus dream.

I was spooning with a woman. And then the dream dissolved. I can’t say that I woke up just then, but I did reach a pedestal higher in consciousness. Then the same dream started reappearing. This time the location of my dream was an office cabin. This time the woman was most certainly her, my love. The dream dissolved again at that very moment, but this time there was a reason to it: a man entering the cabin through a door that had suddenly come to be. The visage of this entrant, this despoiler, remained unclear. It could have been a phantom of capitalism. It could have been a phantom of capitalism.

(17)

We were four of us guys at a friend’s place, drinking and smoking, and scandalizing the already-scandalous broken-engagement drama that one of the guys there had suffered. I ridiculed the guy especially, for what he called love was not love according to me. He had met the girl for not more than twenty hours combined on six different visits.

Anyhow, there was a computer and we got to playing our favorite songs on YouTube. Someone played Nusrat Fateh Ali Khan, the dead Pakistani qawwalist. The song was beautiful, and it led me to thoughts of her. I found in the song a voice substituting for my own, and at that second I would have given an arm for that very sound to enter her ears in all its pathos. But then I realized that even if it did materialize – the miracle of the cross-continental syncing of music, that is – it would be in vain. She just wouldn’t understand the words of the song, the poetry in them.

I decided that I needed to send her a translation. I asked the host for a pen and paper. I repeated in my head the words of the song:

Saanu ek pal chain na aawe – 2

Sajna tere bina – 2

I wrote the following:

I don’t have a moment of peace – 2

Without you O lover – 2

This didn’t work, so I tried again:

There is not one calm second for me – 2

Without you my love – 2

This didn’t work either, and I crossed out the words and made to try again, but by this time the song had ended. The song had ended and that ending gave me a moment to reflect what I really was, or was becoming, and what that becoming was making me do. At once I felt embarrassed by my emotions, by the way these emotions were manifesting, as if their manifestation was an impossibility that nevertheless had to be made possible. Aren’t emotions always so basic, so simple, so kitsch, that the only superlative they can really achieve is embarrassment? I crumpled the paper and threw it inside a large bin that was being used as an ashtray, and inside the bin a hundred or so cigarette butts surrounded my crumpled translation. Someone flicked some ash on the crumpled paper, and the ash slithered through inside a fold, and for a moment I felt that my words had been touched by the remnants of a murderous fire, and that touch was like the cauterization of something inside me, and I was silent and grand and lyrical and tragic and heroic, though ultimately embarrassed.

(18)

By this time Manto has found a bench and is feeding nearby pigeons. Bolaño approaches. They look at each other and then Bolaño sits on the same bench. He asks for a few grains to feed the pigeons.

‘This is a dream,’ Bolaño says.

‘I know,’ says Manto.

Silence and pigeon-song. The sky is greying.

‘I cried when I read Khol Do,’ Bolaño says. ‘It was an amazing story.’

‘Frankly I haven’t understood you yet,’ Manto says.

‘But you’ve understood why …’

‘Why I don’t understand you? Yes, I have.’

The pigeons’ throats glisten purple like the Eastern sky in a Himalayan sunset. The pigeons are out of sync, just like the metaphor of the previous sentence. This dream is really absurd.

‘Liver, you too, right?’ Bolaño asks.

‘Yes,’ Manto replies.

‘I always wanted to die of the lung,’ Bolaño says.

‘Why?’

‘Because of Kafka, maybe even Bernhard,’ Bolaño says. ‘I kept smoking so much all the time, thinking that it would ensure that the only way I could die was of the lung. How silly!’

‘Hmm,’ Manto says. ‘Maybe guys now will want to die of liver.’

There is a sudden reduction in the dream: nothing in it beside these two, the bench they’re sitting on, the pigeons they’re feeding, the catastrophic sky they are under, and the grains in their palms and on the ground. But that is a lot already.

‘I tried to enter, you know, I tried to bore through,’ Manto says. ‘But it was tough for me.’

‘I know,’ Bolaño says. ‘The Third World requires the work of previous ones.’

‘How did you get there?’ Manto says. ‘I mean, inside the thing.’

‘I was born in the abyss, in a way,’ Bolaño says. ‘Or maybe I was always falling. But not without people like you. There were enough like you in Latin America. Or maybe I should say the West. But then it’s not The Third World I’m talking about any more.’

‘What is left to do now?’ Manto asks.

‘For us?’

‘No, for them. Do you think there are others working on it now? In my part of the world?’

‘It’s tough to say,’ Bolaño says, and pauses. It is not a shallow pause. ‘Anyway, it’s not that important you know,’ he says.

‘What? What is not important?’

‘Boring through. Reaching the abyss. For what?’

‘For literature.’

‘But it’s not important.’

‘What is not important?’

‘Literature. Literature’s not important.’

A massive altering within the dream. The pigeons all fly away, simultaneously, as if the wind has turned odious, or as if they had been waiting all the time for the sound of a special word. Manto starts to melt, and sighs while melting. Bolaño flashes on and off. He doesn’t care. Then it vanishes, the dream. All that exists is the absence of a dream, though it smells like burning cigarettes for some time.

About Tanuj Solanki

Tanuj Solanki is a writer based in Bombay, India. His work has been published in Atticus Review, Burrow Press Review, elimae, Annalemma, Out of Print, and others. He is also the founding editor of The Bombay Literary Magazine.