You have no items in your cart. Want to get some nice things?

Go shopping

02 May 1945

Captain Stoddard:

At your request, I have set down a description of my duties from 1933 until the time of my arrest. I have taken the liberty of providing details of a personal nature. Although these may not be of immediate interest to you, I feel they provide a fuller picture of my circumstances.

I was born in 1890 in the village of Ferch to the northwest of Potsdam. My father was the village doctor, my mother its nurse. If this association strikes you as quaint, it is because the Deutschland is different now than it was then.

All my life I wanted to be an artist. Perhaps it is a common ambition in young men of privilege, but in me it was a comical one for I was entirely without talent. I did, however, possess a fascination for the interior of things, a curiosity that leads to the joys of classification, which are meager and few, but are the wellsprings of discovery.

[private]Discipline, obedience, restraint: these were the skills my father strove to cultivate, perhaps because he recognized them as his own. Thus, I learned to shunt the hot wax of my artistic impulses into the mold of the scholar, and the peculiar habits of my youth served me well as a critic and a collector. All things happen for a reason.

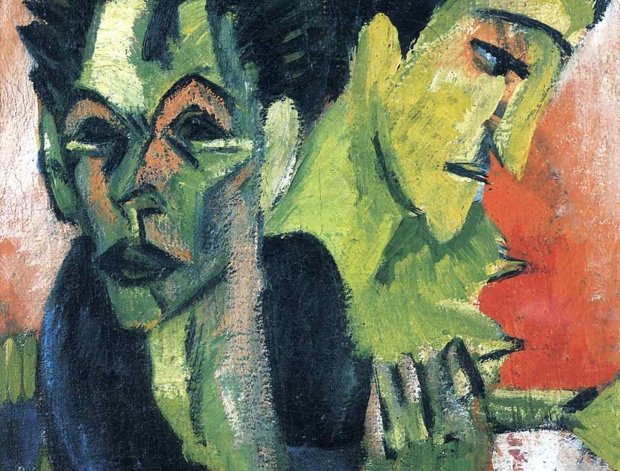

I joined the National Socialist Party in October of 1933. I want to make it clear that my motive for joining the party was to enhance my career. I was not much interested in politics. The world of art was more than enough for my overzealous imagination. Perhaps you think this irresponsible of me; perhaps you have a right to think that way. I understood, sooner than most I think, that the National Socialist worldview was stridently straightforward, and just as there was room for only one Führer, one Reich, and one people, in the world the party foresaw there would be room for just one kind of art.

Uninspired depictions of farm life and rural landscapes hold no great sway over me, and one can only look at so many idealized depictions of Teutonic mythology in the neo-classical style before slipping into a kind of intellectual stupor. These were the works the party championed, and it stood to reason they would, in time, become the only works the Reich would deem suitable for viewing. As you well know, I was right. The new works went up and while the propagandists were busy ensuring that it served their purposes, I made it my business to safeguard the German public from “inferior” art. I amassed, as you might imagine, a handsome collection. I was left to manage things as I pleased. If I had had a title, it would have been “Minister of Degenerate Art.”

I never would have been able to manage all this without my peerless assistant, Alexander Overbruck. I met Alex, the quintessential Austrian craftsmen, during a trip to Madrid. His lungs were so weak the doctors had sent him to the dry climate to recuperate, but his love of Goya was greater than his concern for his well-being and I found him at the Prado working feverishly as a restorer. In Alex I discovered a colleague who possessed the talent I had once yearned for, but without the brashness that transforms ambition into immodesty. I came to know him quite well during my visit to Madrid, and I urged him to return to Berlin with me. Despite my best efforts to persuade him, Alex declined; but he promised to come north as soon as his health permitted.

A year later, he was in Berlin. Alex might have joined me sooner if not for his lingering concern that the political climate might be more detrimental to his health than the harsh winters. His fear stemmed from an accident of ancestry (his maternal grandmother had been a Jew) and his libertine ways. The former was a trivial matter that was easily concealed, and the latter ensured I had an entertaining travel companion. Within a matter of months it became clear that Alex’s talent as a restorer was without equal. He was a master copyist, possessed an eye for forgeries, and was a tireless worker. He was, in a word, indispensable.

I will tell you a story that reveals something of his personality. Shortly after his arrival in Berlin, we were sitting in the parlor of a manor house that had been done up in the Tudor style. The gentleman we were calling on–an officer of the Luftwaffe–was an arrogant boor who had no appreciation for the artwork we were selling him: an exquisite portrait of the Earl of Roquefort by an obscure Frenchman named Frowst. The pilot kept us in a stuffy room, arguing over the price for hours. When Alex had heard enough, he unrolled the canvas on the table and threw open the curtains, flooding the parlor with light. Alex walked the man through the painting, patiently explaining the history of its composition, the merits of its technique. It was all nonsense, of course. Even if the damn fool managed to follow Alex’s fantastic description, there was no conceivable way he could see it with all the light stabbing into the room.

But I saw it. This wasn’t the original portrait, but a forgery Alex had created, and it was a not a perfect forgery: reflected in the mirror above the bureau was the silhouette of a donkey. Alex had turned the Earl’s reflection into an ass. I don’t need to tell you what the repercussions would have been if the correction had been discovered, but Alex was full of mischief.

The war did not adversely affect our business. On the contrary, the way the map of Europe was being reconfigured created favorable situations for the collector who learned to look past his nose instead of down it. You could say it was a buyer’s market. However, when the advance on Leningrad was repulsed, everything changed.

It suddenly became imperative to get the most valuable pieces out of the country lest they be seized, stolen, or destroyed. Alex and I threw ourselves into this effort with great vigor. Technically, we were smugglers; but in the east, or so we were informed, a work of art that did not meet with the Mongols’ approval was slashed with a bayonet and set aflame. We were not going to let that happen to our collection. For a time I feared the Führer might come to regard these assets as a form of currency, a commodity he could turn into armaments for his infantry, but I don’t believe he ever seriously considered liquidating the collection. Alex and I did the best we could. We exerted great caution, in many cases delivering the goods to their new hiding places ourselves. We went to Switzerland, Portugal–places where the people were not gripped by the spasms of war. Alex was particularly fond of Lisbon. It helps that I never tired of his company. During our ten years together we seldom, if ever, quarreled. I miss him desperately.

You may be wondering how we were able to accomplish so much without attracting attention from the party. Please understand that Alex and I were spokes on the great Aryan wheel with the Reichstag at its hub. Senior party members were expected to lead by example, but having neither supervisors nor charges we seldom looked to the Reichschancellery for instructions as to how our business should be conducted and, though we dared not say it aloud, concluded.

As the Red Army’s noose drew tighter, old-line Berliners like myself were quick to realize that what was right for the Reich was all wrong for Berlin. For reasons that baffled me then, and continue to flummox me now, the Führer and those closest to him had reached the conclusion that the perpetuity of the Reich and the preservation of Berlin did not run a parallel course, and it woke us up to the fact that we Berliners had a great deal to lose. If there was a plan to protect the city, it was implemented too late. This failure was devastating. The streets were filled with refugees: men, women, and children whose homes were destroyed and had nowhere to go. It is my opinion that the people of Berlin needlessly suffered, but it wasn’t until Alex made the observation that the rats no longer fled at the approach his footsteps that I realized how grave our situation had become. The liquidation of the city was underway.

Around this time I stumbled upon a painting in the attic workshop that I had never seen before. It depicted a scene from a city under siege. A wave of rodents pursued a howling figure through the rubble. To the left, a man reeled in a fish from the black pool of a shell hole. In the background, hundreds of eyes peered from shattered windows and doorways. A giant cloud hovered over the landscape. When I asked Alex where the painting had come from, he smiled and confessed it was his own. He called it The Fall of Berlin.

It became clear that things on the frontline were not going nearly as well as Goebbels and his army of propagandists wanted us to believe. Then there were the air attacks, which made the nights unbearable. The building shook with such force that we could feel the vibrations all the way down in the basement. Time and time again they knocked down the radio masts and Alex would scurry up to the roof to rig them anew. I begged him not to go, but he would hear none of it. He was, without question, the bravest man I ever knew.

When the Red Army began to attack the city in earnest, lobbing shells at us with their long-range guns, the rooftop became much too dangerous, and we had to rely on other sources for information. Phone service within some sectors remained intact, but communication with the world outside the city became increasingly intermittent. When we managed to get through we still heard that familiar series of clicks that reminded us the Gestapo was listening. The news we received was of a sensational, speculative, or altogether lurid nature. Reports from the front kept our minds in a near-constant state of turmoil. You could say we became numb from rumor. Where facts are lacking, lies abound. But we did not give up. Alex would not permit me to lose hope.

Anyone who was in Berlin will tell you about the smoke. It mingled with the dust that rose from the shelling and was freshened by fires burning all over the city. It was as omnipresent as it was unbearable, a miasma that blanketed the city. Our thirst was intense and we were powerless to slake it. Water was scarce; but alcohol provided some relief and we were seldom sober by day’s end. We dragged our mattresses into the basement, plucked wine from the cellar, and spat great gobs of mucus that was as black as the soles of our shoes. I was struck by how much the city was coming to resemble Alex’s painting.

We had been misinformed about the quantity, quality, and effectiveness of Berlin’s defenses. The Reichschancellery had lost all contact with our armies, and the generals coming in from the field were faced with the unwelcome task of informing the Führer that the armies on his beloved map board existed only in his imagination. There was little sense in being the bearer of bad news. Rattenhuber, with whom I was close, told me staff members who had offices facing the Reichschancellery’s inner courtyard moved to other parts of the building to avoid witnessing the executions.

There were no army groups to mobilize, no troops moving in concert, no secret weapons to drop from the skies. Steiner had failed. So had Weidler’s 56th Tank Corps. General Wenck, our best last hope, had disappeared. Although there were those who groused that that which had never materialized could not be said to have been lost, it was assumed by all but the most fanatical that Wenck’s failure to link up with the Ninth Army Group made it clear that if there was to be an eleventh hour rescue it could not come from the Wehrmacht. All we had left were old men and young boys. The sight of them shuffling down the street in their ill-fitting uniforms to drill in the woods, holding their arms as clumsily as one might handle a shovel, made my heart sick.

We had heard that makeshift fortifications were sprouting up in the most unlikely places–ruined hospitals, abandoned schools, bombed-out factory buildings–and that some of these places housed as many as a thousand men. They had been given submachine guns, grenades, and faustpatronen—a favorite with the young boys who dreamt of destroying tanks with their new toys. I witnessed a training exercise and saw a boy of fourteen teetering with the weapon on his shoulder like a sailor walking a sloping deck. This was our defense? Shameful.

In the Reichstag, where piccolos of chilled champagne were still being served by men in pressed tails, it seemed not so inconceivable that the right man might marshal our motley armies together long enough for the English or Americans to intervene and force a reprieve from what the Russians had in store for us. It seemed not so difficult a task, not with the perpetuity of the Thousand Year Reich at stake; but the rumble of a lone tank motoring down the Königsplatz, fuel tanks sloshing, was enough to make any sane person realize that this was the stuff of fantasy.

I proposed to Alex, faithful Alex, that we quit Berlin at once. Alex agreed. Having determined that we had scant time to waste, I began making inquires. We could not leave without turning over a copy of what Alex and I referred to as The Inventory–our detailed catalog of treasures and where they were hidden.

I asked an anxious member of the Führer’s Special Guard, one of Mohnke’s men, when Captain Gorgast would be available, and he informed me that the captain was among those who were making one last attempt to dislodge the Führer from his apartments below the Reichschancellery garden. The guard did not know when or if Gorgast would return, for he suspected that if the Führer refused to leave, Gorgast would join the others in OberSalzberg. We had the distinct impression we were being railroaded.

That evening, 30 April, I was informed that my appointment with the elusive captain had been postponed indefinitely, but if I liked, I could give my report to an under-secretary named Tensch. Alex and I went to the Reichstag at once. It struck me as strange that the building was unscathed by artillery, when the Tiergarten had been reduced to a field of charred black tree stumps standing in circles of ash. We were taken to a records room in a western wing of the building. I gathered that until recently, this part of the Reichstag had witnessed few visitors: the carpet was plush and had some spring to it, and the upholstered chairs gave off the scent of fresh leather. The chamber in which I was to be interviewed turned out to be a conference room that had been converted into a makeshift depository. The tables were crammed with crates of files, stacks of dossiers, reams of reports. Functionaries sat thumbing through documents and dividing the papers into piles. Others busied themselves by ferrying files from stacks on the floor to the burning trash barrel that sat near the open window.

Tensch was amiable but distracted. He had a broad leathery face of the sort one associated with frontline soldiers. He looked exhausted and he kept staring out the window. The sun had begun its down-going and I couldn’t tell which Tensch found more distressing: his chore or the coming of another night. He seemed not to see me at all.

I told him what I’d come to tell. Tensch muttered, I see, when it was obvious he did not. The man could not manufacture the will to understand the full measure of what I was telling him. At the time this angered me greatly. The destruction of secret documents did not inspire confidence in the government’s pledge that we were safe, and for those of us in the Reichstag, the very object upon which every Red rocket, rifle, and bayonet was fixed, that pledge was all we had. With the complete erasure of the Reich in evidence all around me, I could not help but think that as soon as Alex and I got up from the table and exited the room, my report on the treasures we had amassed would find its way to the trash barrel.

When the interview was over, I found Alex waiting for me outside. Alex, ever the resourceful one, busied himself gathering limes, hard gray-green orbs that had been knocked from the trees by the force of the shelling. He looked like one of Breughel’s wise peasants. For a long time we did not speak to one another. There was nothing to say. It was time to run.

The road to Munich was overrun. All manner of vehicles clogged the throughway: motorized units, jeeps, horse carts and the occasional sedan bearing the National Socialist standard. The people were in an ugly temper and altercations erupted when vehicles couldn’t be moved out of the way fast enough. So many of the people fleeing the city were party members they were calling it the Reich Refugee Road. Everyone had hit upon the same idea at once. We made the Russian’s job easier by acting like a gaggle of frightened schoolchildren.

We moved to the south, but the rubble dictated our course. It made the roads slow going and I could not see how those who had fled in motorcars would be able to make it through the streets. Perhaps they didn’t. Our progress was slow but steady, even if we could not always be certain if we were headed in the right direction. A gray pallor fed by smoke and debris obliterated the sky. There were roads awash in rubble where entire buildings had collapsed, yet in other places we caught glimpses of courtyards utterly unmolested where old women dusted their flowers.

The sound of shelling was the only constant. It neither intensified nor receded, and I had an easy time convincing myself that the sound was the score to a tragic opera, foretold in the mythology of our ancestors. Our Gotterdammerung was nigh. What more evidence did we need?

If one were inclined to make a study of how people behaved when a great society disappears, Berlin provided ample material. Alex and I engaged no one. I love my city, but I had no desire to be pressed into service defending it. A fool’s mission. Soldiers roamed the streets. The S.S. indiscriminately stripped civilians of their clothing and checked them for special markings. To speak of surrender was a death sentence, and executions were swiftly carried out. On several occasions we discovered the way had been blocked by the Gestapo, who in their zeal–to curry favor? Exact revenge? Solidify a reputation for cruelty?–engaged in the wholesale dispatch of traitors simply because they had been authorized to do so. Corpses dangled from lampposts, shiny in the spring heat, a beacon for crows and flies. Broken-necked bodies were flung out of windows, suspended by sheets and sash cords. If one could find a tree still standing it was almost always decorated with the body of a German soldier. These orders were carried out with such fervor that I found it easy to imagine how the enemy must see us. This revelation left me feeling quite unwell. It would be reassuring to know that I was not the only German who felt this way.

What disheartened me the most was the sight of our citizens, thousands and thousands of them, cast adrift in a sea of calamity. They kept telling us there was no army, but I saw them with my own eyes: listless soldiers, useless Luftwaffe men, sailors of every stripe, nurses on bicycles, men pushing farm carts, Hitler Youth recruits, graybeards in their sixties, thin boys in the pale flower of their youth slouching about in pairs, young soldiers clutching at their uniform as if they were ashamed of what it stood for, Mercedes sedans stuffed with soldiers bristling with insolence, wounded men being jockeyed about in wheelbarrows and motorcycle sidecars, entire divisions of men crippled by injury. For the want of a few men with a talent for organization, our once-proud sons roamed the streets like animals.

Our intention was to reach the Potsdam Corridor, but no matter which direction we fled we felt as if we were marching into the teeth of the Red Army’s maw. We encountered a hysterical private who told us his entire unit had been wiped out in an instant. When we asked him how this had happened he informed us the Russians were advancing 650 artillery units per kilometer. We calmed the man down as best we could. He needed medical attention we were powerless to provide. The numbers were so incomprehensible, we regarded them as the ravings of a madman, but we learned, much to our horror, that he spoke the truth.

How had it come to this? I had imagined, and rather naively I admit, that the Russians would come at Berlin from the East, the Americans from the West, and that they would meet at the Reichstag. So you can imagine my dismay when I learned that the two fronts of the Red Army–Konev’s Ukrainian and Zhukov’s Byelorussian–had linked up and encircled the city.

We reached an abandoned factory not 200 meters from the Tetlow Canal. Alex went up on the roof to see what he could see. When he came back down his ashen face betrayed him. I begged him to tell me what he had seen. They’re everywhere, he said. I demanded to know how many, how far, and when he told me–As far as Potsdam–I, too, fell silent. All your life you know that you will die someday, but you don’t know it the way you know that your eyes are blue or that you prefer port to sherry, until death is standing on your doorstep, asking to be let in.

The Potsdam Corridor was closed. It had been a rumor, a cruel ruse. Tempelhof Airfield was our only hope. If we were lucky, we’d find a plane. If we were unlucky, well, we’d just have to make our own luck.

Now greater difficulties faced us. If we went back the way we came, we ran the risk of chancing upon those who might take us for deserters, which, in a narrow sense–the only kind the Gestapo understood–we were. It was a moot point, for our journey was already over. While puzzling over which path was likely to be the least perilous, Alex collapsed. I opened his jacket to loosen his collar and saw the blood. He’d been shot, of course, while he was up on the roof. He had tried to conceal it from me to ensure that I made it out of the city alive. He asked for a cigarette he knew I didn’t have. That’s when I knew that Alex would die. I knew it in the same way that a painting would sometimes reveal itself to me, my understanding so instantaneously thorough and complete that I didn’t need to know anything else about the artist or his intentions, indeed I preferred not to know, because now the work knew me. I put my arms around him and wept.

Alex insisted I go, but I would not leave my partner to die in the street alone. I refused.

He pressed something into my hand, a rolled up piece of canvas soaked with blood. I opened it up and saw that it had been cut from his painting. He’d destroyed it so that no soldier would ever lay eyes on it. His dying wish was that I give him my honest opinion of his work. I told him the truth: that it was masterful yet blunt and not much fun to look at. He smiled and told me to take a closer look. I did so, and there in the bottom corner of the cutting was a hole in the cloud where a single ray of light shone through.

That’s you, Dieter, he said with his last breath.

That is when your men found me, Captain. To their credit they treated us with dignity. I wish there was a way I could repay you for that, for it says a great deal about the kind of leader you are.

As for the inventory, I am afraid I cannot assist you. Alex copied every major work that came into our possession, often several times. We disseminated so many fakes and forgeries throughout Europe it would take a lifetime to hunt through all the private collections and separate the copies from their originals. Perhaps it was foolish of me to entrust all of Europe’s degenerate art to a mass producer of fakes, but I could deny Alex nothing. He is the only one who knows where the originals are and now he is gone.

My past is clear, my conscience is not. For some history is as distant and remote as a patch of land seen through dense fog, but not for me. I should have taken Alex to Lisbon where he could pursue his own work in his own studio and drink in all the warm air and sunlight he required. I do not regret the loss of the art that slipped through my fingers; I mourn the masterpieces Alex will never create.

Captain, we live in a world that finds lies preferable to the truth. I wish you the best of luck sorting them out.

Yours sincerely,

[REDACTED][/private]

About Jim Ruland

Jim Ruland is the author of the short story collection Big Lonesome and co-author with Scott Campbell, Jr. of Giving the Finger, forthcoming in 2014. He has been a columnist for the indie music zine Razorcake since 2001 and writes the book review column The Floating Library for San Diego CityBeat. His work has appeared in The Believer, Esquire, L.A. Weekly, Los Angeles Times, Oxford American and is forthcoming in Granta. He is the curator of Vermin on the Mount, an irreverent reading series based in Southern California, now in its ninth year.

My short story, “The Fall of Berlin (Oil on Canvas,” live today in the UK @LitroMagazine

https://t.co/zRq11eJuPE

Das ist gut.