You have no items in your cart. Want to get some nice things?

Go shopping

“It’s a scam.”

This habit, of reading email over his shoulder uninvited, was one of several reasons that had led him to conclude there was no future in their relationship and that he would leave her, at the right moment, soon. It would be soon.

“That’s what I thought,” he said, “But look.”

She leant in closer, her hands on his shoulders. She read the paragraph he indicated.

“So? You can find anything on Google.”

“She died in 1985. There wasn’t any internet.”

“Richard III died in 1485. He’s still on Facebook.”

He shrugged her hands off his shoulders. Who knew when Richard III died?

Esther did; which was another reason. Every smart word made it more certain that he’d go, that he’d have no choice but to meet the guy, prove her wrong. Couldn’t she see that?

Soon.

***

The café was dark, even in the early afternoon, and very nearly empty. His new brother – half-brother; Oliver – sat in a low sofa, facing the door, the heavy wooden table in front of him no higher than his shins. There was an empty mug on the table. Geoff expected him to stand up, to shake hands, probably, but he didn’t. It was a good sign. If he were not in fact Geoff’s brother, but some sort of conman, as Esther insisted, he would have stood up. He would have been more ingratiating.

Geoff said, “You were right about the moustache.”

It was probably a tic, Geoff thought, a Pavlovian response, the way he stroked his moustache, as if he were checking it was still there, the moment Geoff mentioned it.

“Would you like another coffee?”

From the counter Geoff turned back to ask if Oliver wanted sugar. He seemed to be looking straight ahead, at nothing, as far as Geoff could tell, and certainly not at Geoff. Another good sign. His mouth was open; thick black whiskers curled over his upper lip. A Zapata, he’d called it in his email: you’ll spot me. When he read that, Geoff wondered if he might be planning to grow it specially, just for their meeting, like wearing a buttonhole on a blind date, or carrying a certain newspaper to a certain park bench for a betrayal of secrets, but now he saw this wasn’t the sort of moustache you could grow in a few days. He’d never seen facial hair so luxuriant on anyone so young. His father – their father – had grown a beard once, but it was a patchy, etiolated affair, and Geoff’s mother made him shave it off. Oliver’s moustache was like a well-fed animal: fat, lithe, contented; it seemed more alive than the rest of him. He didn’t look much like their father.

Geoff placed both coffees on the low table, and sank carefully into the sofa opposite Oliver’s. They were too far apart for easy conversation, but sitting next to each other wouldn’t have felt right, either.

He said, “OK. So this is weird.”

***

Later, Esther said, “What did he want?”

“To talk about our father.”

“Which art in heaven?”

Another reason.

“Not funny, Es.”

“Your rich father?”

His father wasn’t rich, not really. Geoff was his executor, and knew exactly what his father had been worth, at least when he died. He’d run a business selling fencing materials, supported Geoff’s mother after they divorced, owned a flat in the city and a house in the country, but it was a small house. You might call it a cottage, he used to say, except it was too ugly, and not anywhere anyone else much wanted to live. Geoff suspected that was the point; he’d never been there himself. When Esther asked, he said he couldn’t remember whether he had mentioned the cottage first, or Oliver had.

***

On the motorway Ollie – Oliver sounded too young, he said, too posh – wound down the window on his side. The noise was deafening. Geoff said, “Would you mind?” and Ollie wound it up again.

He hadn’t seemed that keen to come and Geoff, who had only suggested it to fill a hole in the conversation, found himself pressing the invitation, even though the idea of spending a weekend with Ollie made him squirm in anticipated embarrassment. Ollie said he was useless at DIY; Geoff said it didn’t matter. He wasn’t planning to renovate the place, just to take a look, decide if he should sell, or maybe rent it out.

After another hour there was a service station. Geoff suggested they stop for a break. Ollie didn’t reply, but Geoff pulled in anyway. When he came out of the gents, Ollie was smiling, the moustache pushed up high on his cheeks. He was holding a small, pink stuffed animal; Geoff thought it might be a rabbit, but it was hard to tell. Ollie said, “Those grabbers, if you go for the expensive stuff, they always drop it.” Behind him, in a glass case, a three-fingered metal hand hung over a brittle cornucopia of watches and cheap jewellery, cigarettes and cuddly toys. He offered the rabbit to Geoff. “You can give it to Esther.” Geoff imagined the look on Esther’s face, and decided he just might do it.

When they turned off the motorway there was nothing much to see.

***

On Sunday night he told Esther he was going to keep the place. He said he could see himself repainting the windows, growing a few vegetables in the garden.

“Keeping a pig?”

“No, not keeping a pig.”

“So what are we going to live on in this rural idyll?”

Geoff realized he hadn’t pictured Esther in his father’s house at all.

She had a point, though. The house was five or six miles from the nearest village, and there wasn’t much when you got there: a pub, a shop, a church and a Baptist chapel, a bus shelter full of cigarette butts and half-hearted graffiti. The bus took almost an hour into town, the woman in the shop had told them. He’d reminded Ollie of this on Sunday afternoon, when Ollie said he wanted to stay on, that he wasn’t going back to the city with Geoff. Ollie had shrugged. He’d be all right, he said.

When he told her, Esther said, “You left him in the house?”

He said Ollie wouldn’t come to any harm, and she stared at him for a while, not saying anything. He said Ollie had promised to make a start on the windows.

Esther went back to ironing blouses for the week ahead.

***

On Friday morning Ollie texted while Geoff was at work and said there weren’t any tools. Geoff rang back and told him to look in the garage. Ollie said it was padlocked. Geoff had found a drawer in the kitchen full of odds and ends: screwdrivers, blunt knives, nails, insulating tape; he told Ollie to look there for a key. He asked if Ollie were in the village: his father had always said there was no signal.

Ollie said no, he was in the house.

***

That afternoon, after work, Geoff drove straight out of the city. It was dark by the time he turned off the motorway, and darker still in the woods that surrounded the house. They weren’t the kind of woods you’d want to walk in: densely planted conifers that blocked out the sun on the brightest of days. He’d taken a wrong turning in the dark and it was almost eleven when he pulled up outside the house. All the lights were on, and he could see Oliver upstairs, in their father’s bedroom.

He let himself in. The kitchen was tidier than he’d expected. There was no washing up in the sink, no empty beer cans anywhere he could see. In fact, it was cleaner than it had been when he’d left last week.

Ollie came downstairs wearing a tweed jacket. He said, “Was this Dad’s?”

Geoff didn’t recognize it. “Where did you find it?”

“Upstairs, in the wardrobe.”

Geoff had slept in their father’s room the previous weekend. At night he’d hung his clothes over the back of a small wooden chair. He hadn’t liked to open the wardrobe, or the drawers under the bed. Ollie had slept on the sofa in the sitting room.

“It must have been.”

To be fair, Ollie had made a start of sorts. He hadn’t scraped the flaking paint from the window frames, but he’d at least cut back the ivy that had grown over most of them.

***

The following weekend, Geoff couldn’t get away. It was his birthday, and Esther had invited Anthony and Cheryl for dinner. Anthony had been Geoff’s best man.

For his birthday Esther gave him a shirt, a book and the cuddly pink rabbit he’d given her. The shirt was a rich, emerald green and beautifully cut. He liked it very much, although it was perhaps a size too small. The book was Moby-Dick, which they’d both read, years earlier, and which they’d given away in a backpackers’ hostel. He couldn’t remember what they swapped it for. They’d both enjoyed Moby-Dick, though, and he was pleased that she remembered.

After he’d unwrapped the shirt and the book and opened the card from his mother and the card from Esther’s mother he said, “Was there anything from Ollie?”

Esther said, “He’s not your brother. Your father wanked into a bottle twenty years ago, that’s all.”

That evening he wore the new shirt. Esther made the fish soup she always made when they had friends over, and Geoff managed to spill some on the shirt. Cheryl said it would wash out, but Esther thought it wouldn’t.

***

The next weekend he found the cottage without any trouble and it was still light when he arrived. He could see the window frames had been freshly painted. He wouldn’t have chosen that shade of blue himself, but it looked like Ollie had done a decent job.

He let himself in and found a woman he’d never met in the kitchen. She was sitting at the table with her bare feet pulled up on the chair and her arms around her knees, and seemed to be all limbs. She said, “Hi, I’m Abby. Would you like lasagna?”

She uncurled her legs and pulled a clean plate towards her. Ollie came into the kitchen. When he saw Geoff he said: “Oh, hi. This is Abby.”

Abby said, “We’ve met.”

Ollie hadn’t shaved, and his moustache was losing definition, dissolving into a beard. Geoff thought it didn’t suit him.

That night Geoff slept on the sofa, Ollie and Abby in the bedroom.

***

During the week he tried to read Moby-Dick but he was pretty tired after work. Esther asked if he was enjoying it and he said he was. But he kept falling asleep and it didn’t seem to make much sense. He decided to save it for the weekend.

He wouldn’t go to the cottage this weekend. He’d stay at home and they’d have a lazy time together.

On Saturday, Esther ordered a take away and they drank a couple of bottles of wine. They watched a DVD and when it ended she kissed him and undid his trousers.

He was going to leave her soon.

On Sunday he made breakfast for them both and took it back to bed. He read Moby-Dick for a while.

They went into town, to an exhibition and then to the pictures. In the dark cinema, in the middle of the afternoon, he pictured Ollie outside the cottage, splitting logs with a long-handled axe.

Back home, he had another go at Moby-Dick. He would finish it now, he knew, but he wanted it to be over. It wasn’t that he didn’t like it, or that he knew already what was going to happen. He didn’t. Ahab wouldn’t get the whale, but other than that, he had no idea.

It wasn’t that he knew how it ended.

It was just that it had all been going on long enough and he wanted it to be over.

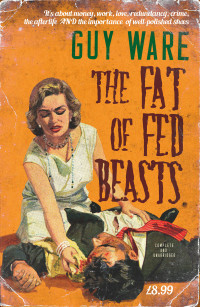

Guy Ware’s novel The Fat of Fed Beasts is ambitious, genre-defying, and very funny, tackling life’s big questions (you know the ones – money, work, crime, the afterlife… the importance of well polished shoes). Ware has delivered a pacy, constantly surprising and stylish novel which asks why we do what we do, whether it matters, and what, if anything, our lives are worth.

Guy Ware’s novel The Fat of Fed Beasts is ambitious, genre-defying, and very funny, tackling life’s big questions (you know the ones – money, work, crime, the afterlife… the importance of well polished shoes). Ware has delivered a pacy, constantly surprising and stylish novel which asks why we do what we do, whether it matters, and what, if anything, our lives are worth.

It is released on April 16th by Salt Publishing, and is available here.

About Guy Ware

Guy Ware is a recovering civil servant. His story collection, You have 24 hours to love us (Comma), includes a story first published by Litro when it was a single piece of paper. His first novel, The Fat of Fed Beasts, is published by Salt. Guy's heart is in the Highlands, but his mortgage is in New Cross.