You have no items in your cart. Want to get some nice things?

Go shopping

Dinah Craik first announced herself to me on a wet summer weekend in Hay. I was shuffling along a narrow street at the tail of a crocodile formation, savouring the sweet acoustic residue of an audience with Gruff Rhys, when she caught my eye. Perched in the corner of a large window, at the front of a shop I’d not previously registered, a filthy green hardback with a title too perfect for the coming month demanded a closer look.

I broke from the crowd and pushed through the door. A stiff clink chimed into the dense room, announcing my arrival, but nothing moved and nobody stirred. The space was a clutter of books and pamphlets. I shook the rain from my Mac and made for this strange thing that had called out to me so loud and clear.

“Good afternoon.”

I turned sharply – catching my heel on a fifth or sixth-hand copy of W.G. Sebald’s The Rings of Saturn – to see a short woman of about 60 resting her arms on the low counter. Unable to restore my balance, I fell flat into a pile of Romantic poetry. “Oh, poor love. Are you okay?” From a bed of Keats, Byron and Shelley, I watched this slight, somehow angular woman glide like a spectre across the floor. Standing with her arms folded, she looked down at me. “You’ll have to watch your step if you want to get out of this town alive,” she laughed, curling the ends of her words with the heat of a Welsh-valleys tongue.

As I stumbled to my feet, clumsily knocking more books to the ground, she brushed and smoothed my shoulders and chest. “What can I help you with?” I reached towards the window display, but to my astonishment the book was gone. I swivelled back round to find the strange woman leafing through the thick pages, her pale profile engrossed and amused. “Ah, Miss Mulock’s Victorian travels, a good choice. It’ll cost you a fair old penny – out of print, you see.”

I explained that I was heading to the south coast in two weeks and was interested in the text, but I’d need a few minutes to decide. “Take your time, love. I’ve got a bath on the go upstairs, so pop your money on the top when you leave.” She patted my arm and floated back out the way she’d come in, leaving a vapour of brown beads rattling in her wake.

Lighter than it looked, An Unsentimental Journey Through Cornwall was cold to touch and wrapped in a crude plastic coat. On the front, a girl – a maid, perhaps – stood sketched in the garden of an old stone post office. She was reading from a large sheet of paper and wore a look of sincere concern. As I glanced over the first sentence of the foreword, a gust of wind clattered through the door and raced along my spine. In a haze of adrenaline, I tossed the cash on the counter and made out onto the cobbled road with the book stashed firmly under my arm.

I took one last look at the shop, which now seemed completely derelict, and hurried back into the crowd.

*

Sat in a busy café, sipping tea and picking at a hard, syrupy flapjack, I considered the text, unsure as to whether or not I should open it again. I hadn’t yet located the writer’s name – the front simply read, ‘By the Author of John Halifax, Gentleman’. I pulled out my phone and tapped the Safari icon. In the next second a flush of air flapped hard like a bird trapped in my throat and a Wikipedia page appeared unprompted on the screen: ‘Dinah Maria Craik (born Dinah Maria Mulock, also often credited as Miss Mulock or Mrs Craik) (20 April 1826 – 12 October 1887) was an English novelist and poet’ – a bull-necked sepia portrait staring straight through me.

Her death was exactly one hundred years to the day – perhaps to the hour, to the very minute – before I was born. I looked around at the faces of my fellow diners, all melting into the cheap artwork on the walls: silhouettes of trees clustered on the banks of the Black Hill, a mallard paddling beside a rowboat on which two brothers had turned their backs to the world, casting their lines after peace and quiet.

Her hand closed around my collarbone and I came to with a start.

“Did you find anything good?”

*

For the next few days, at our home in Hackney, we kept Dinah’s work at a distance, but it did something to our lives, tunnelling into our plans.

For a month now we’d been eagerly anticipating a walking break, exploring a myth-laden stretch of wild Cornish countryside, starting near Falmouth and making our way round to the Lizard coast. I’d had a pitch for a disgracefully generic travel piece accepted by the Guardian, the income of which would pay off the overdraft we’d used to fund the trip. We planned to camp mostly but pencilled in one night at a Falmouth hotel and two or three more in B&Bs along the way. Nothing final, as of yet.

One evening – just days after Hay – we returned from the pub and fell into a shallow sleep in front of a Douglas Sirk film. (Our flat is spread over the first two floors of an old Victorian house, damp but comfortable.) As a curious picket-fence melodrama played out like a mirage on the TV, I was roused by a scratching sound, a rat or bird in the wall panelling, and caught sight of a sturdy woman dressed in a black hooped skirt and poke bonnet. She was standing dead still in a pool of bloodless moonlight at the kitchen window, looking out over our small, enclosed garden.

Unable to move, my breathing stuck in the slow depths of sleep, I watched as her head began to turn on her broad shoulders. I awoke fully with a jolt and sat panting, my palms soaked in sweat. I made for the office, flicked on a lamp and took the book from a pile in the corner; I flung it open on the desk, cold under hand, and started to read.

*

Born to a pastor in Stoke-on-Trent, Miss Mulock moved with her mother and two young brothers to a small house in Hampstead in the mid 1840s. She proceeded to write her name in history, not pressing her pen too hard, with a brand of novel celebrating morality and domestic virtue. As well as a poet and popular London personality, she was a pioneer of literature for young people. Despite considerable commercial success in her time, her strong features faded into the fog from which the Brontes, Austens and Gaskells of this world strode forth.

Reading, by lamplight, her reflections on that unsentimental journey, with a summer storm raging against our rotten window frames, threw me into a trance-like state. For days I trawled through her life and works online – and in print where possible. I barely recall purchasing her thoughts on Ireland, An Unknown Country, from a market stall under a Hackney railway arch. The seller wore a battered pair of Hi-Tech tennis trainers and a North Face fleece zipped to the throat. Otherwise, it was but a vague dream.

While the goodness of her main body of work – including the aforementioned John Halifax – is, according to some, too self-righteous and one dimensional for modern readers, I found her later travel pieces mysteriously current and intriguing. I was struck by a swirl of déjà vu and coincidence, synchronicities between her life and mine – the similarities slight, but unsettling nonetheless.

Two nights before embarking on our own adventure, I came across a poem titled ‘Philip My King’, written for her godson, the poet Philip Marston. That name splashed into a pool of recent memory. I recalled reading, not two months previous, The Levelling Sea – about Cornwall and the age of sail. Published in 2011, it was written by Philip Marsden, whose uncanny phonic resemblance was the kind of ghostly fluke I’d grown more and more familiar with since Hay.

I thought of Marsden’s description of an early guidebook, published in 1815, and how its authors didn’t see Falmouth as a place to stay, but one at which to stopover. Despite much having changed in the years before her visit, Dinah refers often, albeit in little detail, to her own guidebook. She describes spending one brief night enjoying the ‘comfort and homely peace’ of the Greenbank Hotel – where we, incidentally, would begin our trip, thanks to the advice of a dog-eared guidebook given us by my parents. Our routes from there were nigh on identical.

I found, too, that John Halifax was inspired by Craik’s time in Tewkesbury, the Gloucestershire town where my mother raised my sister, before uprooting to South Wales. At the end of the 19th century, a marble medallion was placed in the author’s memory in Tewkesbury Abbey, which is overlooked by a hill on which my 20-something mother spent spring afternoons flying homemade kites, after lunch and a pint at The Bell across the road. We’d stopped off at the church countless times ourselves, on expeditions to my grandma’s cottage, most recently just three weeks previous.

As I say, this strange sort of occurrence had become commonplace: coincidence and déjà vu conspiring to hook fragments of one story to the tail of another, knitting together a complex reality for us to tramp with our eyes peeled and nerves pricked – disturbing, disorienting and affirming all at once.

I snapped out of that chronic daydream in time to catch my breath and pack some clothes.

*

The drive south was cast in a blaze of sunshine: golden-grey motorways rolling like Saharan dunes, dry-green and gridded countryside lurking somewhere beyond our periphery. Near halfway there, we eased into a sludge of traffic. Queue cautions and accident-up-ahead signals arrived in specks of neon orange, fighting for clarity against the burning glare of summer.

As the radio told us in a soothing monotone about Twitter and the brutal nature of modern shame, I imagined the smash in the distance: a maroon-coloured Ford Mondeo, a white van stacked full with cases of Malbec, and a blue Renault Clio carrying three stoned teenagers – a hole cut deliberately in the exhaust for effect.

“The stocks in the town square are back, public humiliation is rife and it’s all gone digital.”

The van was hogging the outside lane, refusing to give in to the irate Mondeo pressing close behind. The Clio slid up on the inside and a jittery 17-year-old, feeling the heat of conflict, panicked and pushed hard on the accelerator in hope of clearing the threat. At the same time, the van driver folded under the Mondeo’s pressure and steered sharply into the middle lane, clipping the Clio’s wing at 85 fatal miles per hour. Friction flipped the latter into a somersault, the van spun out of control and the Mondeo torpedoed into the silver guardrail.

“Yes, there is an argument that it’s a good thing if we’re talking about serious wrongdoing, corporate corruption and the like – yeah, for sure.”

Three passengers lay dead, two drivers, too, while another watched through a haze of burnt rubber as thousands of pounds worth of Argentine red spilled like blood onto the sizzling road.

“But when it’s just one person making a single idiotic comment it’s a wholly different matter.”

The crash passed in flashes of data away from the scene, racing down the line of slowing vehicles like a voice in volts along a telephone wire, first in thumping arteries and profanities, then in mute shock and soon just mere speculation. It was all just mere speculation. The story spread from the M5 in soulless sentences spewed on cluttered social media feeds, leaking warped fragments of devastation into bedrooms, bars, gyms, supermarket car parks, monstrous shopping malls, and onto the greens and fairways of serene golf courses.

“We’ve reached a point where one ill-considered joke can mark the end of life as we know it. Because of our own insecurities we vilify the perpetrators of any given misjudgement and drive them out of society with pitchforks. We have become so disgracefully unforgiving, which is symptomatic of an even bigger problem, a phenomenal sickness.”

“Do you reckon we shame people simply because we’re insecure?”

“Huh?”

“You know, because we want to feel like good people?”

*

We arrived at the Greenbank Hotel, dumped our luggage and took a seat on a balcony overlooking the Fal estuary. Hundreds of yachts were pulling into port for the town’s annual boating festival. The harbour, thought to be the third largest of its kind on earth, was playing host to a dance, a parade of colour and sail. I thought of Dinah and her two young nieces brought along for the ride. I imagined them on their first night in Cornwall, watching the tide work its way into the wilderness, towards the Lizard lights. We ate three scones and set off to make the most of the dying day.

On a recommendation from the concierge, we drove out to Mylor Bridge, where a brief walk along two creeks would see us to the Pandora Inn – “as good a place as any for Cornish grub and ale”.

Mylor Creek was dry, but for the odd pool of festering rainwater. A strange landscape stood still before us, frozen in time – boats named and then renamed Caesar, Augustus, Richard III and Maggie’s Farm sunk in a muddy hibernation, crooked like gravestones, relics from another age. We read their histories in hefty dents and flaking coats of paint. They implored us to imagine the storms, the tempestuous nights at sea and the tragedies they’d seen. We attacked the route in silence, the cry of gulls and the caw of one regal-looking chough for company.

Dinah wrote incessantly of wrecks and death. Her book describes countless marine catastrophes – sailors giving their lives to the boiling waves and ruthless currents. We were to visit a place called Pistol Meadow in the coming days to pay our respects to the 200 seafaring dead of the Royal Anne, who, due to some absurd religious logic, were denied the comfort of consecrated soil. Many more met with the same fate. ‘Most of them,’ Craik wrote, ‘being interred as near as convenient to where they were found.’

Along a narrow slip – the final leg before the inn – we stopped and peered over hedges at rows of faux-thatched cottages, elite holiday properties that creaked in summer and slumbered through the long winter months. I saw, or perhaps imagined, third-home politicians in deck chairs, perusing the Telegraph with grotesque guts hanging loose, sunburnt. “It’s bloody gorgeous here.” The hum of smart phones mingling with birdsong.

At the pub (erected in the 13th century, burned to the ground in 2011 and resurrected since, low beams intact) we ate creamy fish pie and watched a red-haired child race the length of an obscene pontoon, wielding a tattered green net for crabs. A beer-sodden pamphlet mythologised the past for us, riffing on the spot’s history. It explained how, once a farm, the building suffered a series of identity crises: Passage House, The Ship and finally the Pandora Inn.

The last and enduring title came from the HMS Pandora, which played a notable role behind the scenes in Frank Lloyd’s 1935 Oscar-winning Mutiny on the Bounty and Lewis Milestone’s ‘62 effort of the same name – Marlon Brando and Trevor Howard no doubt boozing in Portsmouth before setting off on rough seas for Tahiti.

In keeping with its Greek tag, the Pandora, captained by naval officer Edward Edwards, met with unimaginable horror. Sent to retrieve Captain Bligh’s mutineers – Brando and Howard violently split, one set adrift, the other given to flame – the ship crashed into the Great Barrier Reef; with its destruction, 35 men were condemned to the deep. The captain survived to face court martial on his return to the UK – to Cornwall.

I looked up from the page to see a restored sixth-rate warship ghosting through the creek. We agreed this was a tale custom made for Dinah, should her path have pointed east instead of west.

*

The corridor walls of the Green Bank Hotel bore images of Thames Valley wildlife: toads, badgers, water rats and moles, otters, weasels and wayfarers. By way of explanation, Kenneth Grahame stayed in our room in 1907. Word has it he gathered ideas for The Wind in the Willows on boat trips from Fowey – beetroot and black-pepper sandwiches drenched in vinegar, dreams of sightless spring-cleaning, haywire motorcars and unlikely cross-species friendships.

I remember, as a child, my father calling me from downstairs, waiting with plates of bitter marmalade on toast and a VHS crackling on screen – the Wild Wood and Toad Hall animated for Saturday-morning splendour, future bouts of nostalgia. Outside, silver dew had settled on the broken turf of our local football pitch, lifting the dawn up and over reality into the realm of fantasy. I had the book, too, and a psychedelic ride at Disney World.

About that time Dad took me to Blackwood, where his father grew up, before chasing pay to the East End of London. The town was grey and glorious, bustling with phantoms. Years later, I read strange stories of an amateur wireless enthusiast, a radio man residing in the Old Mill, catching early distress signals from the plummeting Titanic; Chartist leaders John Frost and Zephaniah Williams frequenting the Coach and Horses, designing violent revolutions over heavy, unfiltered pints of beer. South Wales is forever hoarding secrets.

Back in the present, we fell asleep watching On the Black Hill (Andrew Grieve, 1988) from a laptop perched on my chest. I awoke soon after to the sounds of thunder and footsteps creeping in the dark, my computer upturned on the floor. I pulled it back onto the bed and rolled over to find Chloe unmoved beneath the sheets. I flashed the bright screen in the direction of the noise but could make nothing out. The door was ajar.

The passageway, at 2:00am, was swimming in waves of blue shadow. At the far end, a trail of frayed fabric slithered beside the skirting board and slipped around the corner, out of sight. I followed, drunk on sleep and curiosity. Placing my hands on the banister of the main stairwell, I leaned forward; the smooth mahogany groaned against my weight. A black frame shuffled below, wading through a thick plume of mist, before a second figure appeared, suited and booted, and linked her arm. Tilting his head, he smiled to reveal a mouth full of loose teeth and bleeding gums. “Good evening,” he said.

Floating in pursuit, I came upon a Kubrickian scene: the ghastly pair sipping whiskey, legs crossed, in a skunky haze of drawing room smoke, discussing the science of wanderlust.

At breakfast, it was all a blur, my head spinning to the noise of clinking glass and the distant laughter of two young girls.

*

Later that morning, we joined the South West Coast Path and trekked roughly 12 miles to the Helford Passage. The start of the route took us by Falmouth Docks, with its brief-history signage, to a path below a fierce country road. Snacking on handfuls of sour blackberries, we stopped to photograph the view from Henry VIII’s Pendennis Castle across the water to St Anthony’s lighthouse. Built originally as a defence against the French, the castle is now occupied by misremembered and repetitive mannequins, recorded summer fantasies of the Siege of 1646: BBC4.

On a narrow trail, winding down to the summer-holiday bustle of Swanpool Bay, Chloe took Dinah’s book from my bag and began to read aloud:

“In the dim light of a newly-risen moon, everything looked so solitary and ghostly that we started to see moving from behind a furz-bush, a mysterious figure, which crossed the road slowly, and stood waiting for us. Was it a man or a ghost, or…”

Trembling, Chloe coughed and cleared her throat; she looked at me, pale-faced and glazed in sweat.

“Only a donkey! A ridiculous grey donkey,” she laughed. “It might have been Tregeagle himself – Tregeagle, the grim mad-demon of Cornish tradition.”

She collapsed forward and vomited two heaves of brown matter into a cluster of wild marigolds.

Jan Tregeagle, we later learned, was a 17th century magistrate of devious mind and foul disposition. Despite something of a Dickensian redemption, the afterlife was not kind to his rotten soul. Dragged from the grave to testify in court, Jan was hounded by a troop of ruthless demons, before finding sanctuary with the church, who gave him a series of tasks to complete ahead of Judgement Day. Having toiled at Dozmare Pool in Craik’s time, he can now be seen frantically sweeping the sand from Porthcurno Cove, his exasperated howls whistling on the wind.

At some point in the mythology, Tregeagle’s spirit was led by chain to Helston, not to be confused with the Helpston made famous by John Clare, the Northampton Peasant Poet who fled his Epping Forest asylum and foundered all the way home; he travelled 80 crippling miles with no money or food, but for the occasional meal of delicious grass from the roadside.

Clare’s terrible ‘Journey Out of Essex’ was re-remembered more than 150 years later by psychogeographer Iain Sinclair, in his book Edge of the Orison. Like me, Sinclair was born in South Wales and stumbled in his twenties to the metamorphic labyrinth of Hackney, his Rose Red Empire far removed from mine – Marxist booksellers, poet-friendly rents and a distinct lack of weekend ‘balloon babies’. But his wife, Anna, faced day-to-day trials akin to Chloe’s, in the stuffy classrooms of local primary schools.

Prior to our trip, I met Sinclair at the Hackney Picturehouse to discuss his and Andrew Kotting’s fictional documentary By Our Selves, resurrecting Clare’s delusional ramblings, this time with a straw bear for company – ‘ghosting through a middle-English landscape of wind farms and hedgerows,’ I wrote; all slippage and collision. Two days later, I chased the Helpston Poet to the Romantics section of the National Portrait Gallery, where I was told by a polite receptionist that five versions of Dinah were in storage, gathering dust.

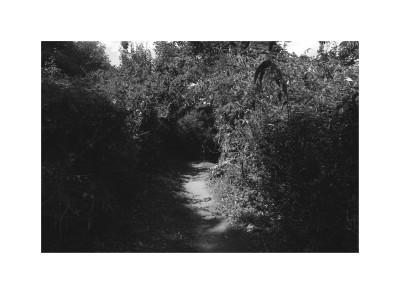

After a large swig of water, we traipsed on. Our cliff-top path weaved back and forth between bulbous knots of bramble and thick sprays of haunted wood. We passed hidden coves and found two tattered deck chairs beside a war memorial built to face the blistering sea.

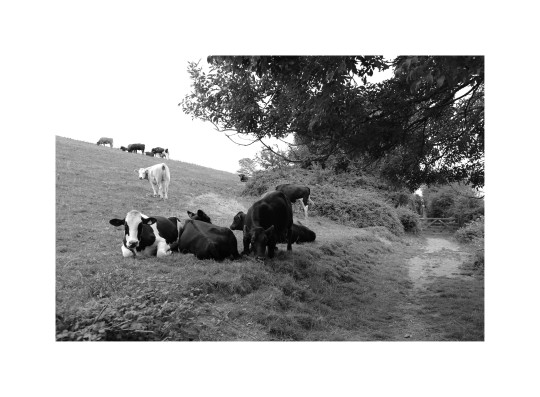

Our walk descended into dream, a squawking chough, armed with Arthurian legend, hovering just above our heads. At the Helford River, we strayed from the mapped route and fell into a system of pasture fields lined with scarecrows and hedgerows. Cows blocked our path and stared stupidly as we climbed over broken stone walls into graveyards and made lists of the dead. Beyond Durgan, an idyllic holiday hamlet within the surprising reach of Sainsbury’s deliverymen, we climbed to the hump of a yellow hill. We paused and looked out over a crisp green and blue canvas.

We pushed on to the Ferryboat Inn, where as a child I watched Phil Mitchell play pool and guzzle ale with a bald, barrel-chested friend; games of Risk out front and Ashes-imitation cricket amid the clutter of the car park. We bought pints of sweet cider and dined al fresco on mussels pulled fresh from the river – diesel wafting on the evening air. As the sun dipped below the orange horizon, a male-voice choir turned out in jeans and beer-stained polo shirts, swaying drunkenly between tables to the rhythm of Bobby Scott, Ewan McColl and Peggy Lee.

The songs called to mind Terence Davies’s film Of Time and the City: ‘He Ain’t Heavy’ the new soundtrack to hijacked images of the Korean War, ‘Dirty Old Town’ retuned to Liverpool, and ‘The Folks Who Live on the Hill’ given over to the black and white skyward rise of city life; a stunning collage of appropriated memories, ecstatic truths shimmering in full flow.

That night, we slept in a field.

*

The following days passed by in a semi-conscious drift of shattered time. Bleary-eyed and sun-stroked, we wandered from place to place, occasionally staggering from the clearly-marked rural tracks into some neglected edge-land or other: subterranean peregrinations in Trelowarren; serpentine cottages lining the electric leys to a heath that thrives mysteriously on magnesia; cinematic bus rides from St Martin to Poltesco, back on foot to Cadgwith and on to Lizard Point.

We spiralled out of control, into an immediate present fizzing with the immediacy of the past. Our strides criss-crossed and zigzagged; we lost all sense of direction, of forward motion.

After two cups of black coffee in the shade of the lighthouse, we descended the steps to Pistol Meadow, for a picnic with the gruesome crew of the Royal Anne – spirits in limbo, watery lungs, just enough room for one more chicken-mayo sandwich, harking back to the days of 1720.

At Kynance Cove, we undressed on the sand and spied a ludicrous figure in rogue fisherman’s dress. “John Curgenven,” he said. “I don’t believe King Arthur ever lived at all.” A fine man, rich with Cornish candour, he took us out into the boiling waves and told us of a trio from London he’d met earlier in the week. He reeled in three mackerel and fed us on the shore, kind-eyed and grey, a wild man of the coast. Our chough picked at the fleshy remains.

*

“Had your fill?” She asked, beaming rosily from ear to ear.

“Yes thanks, Miss Mundy.”

We cleared the oak tabletop and poured ourselves more tea, sitting back to digest a banquet of bread, butter and blueberry jam. On the bench opposite, a strange man – prone, we found, to voluble and nonsensical speeches – rolled a cigarette and took deep successive drags, black tar accumulating at the roach. We watched Mary glide about her tasks, chattering away enthusiastically.

“He is no longer Death the Enemy, but Death the Friend, who may – who can tell? – give back all that life has denied or taken away,” she quoted. “Remember me to Mrs Craik when you find her, won’t you?”

We slipped from the Old Inn out into the night and camped on the move, gulping wine and talking in tongues. At a lamp-lit crossroads, pixelated by midges, a horse-drawn cart clattered from the gloom and ground to a halt. A young man dismounted.

“You lost?”

Laughter rose from inside the carriage and faded as we sent them on their merry way. We followed their course, from a distance, right through till morning.

*

I ran my stained fingers along a patch of matted grass and pulled sandy clumps from the ground, holding them out and shaking wet soil onto our bare knees. The beach lay beneath a pillow of mist cut through with first light, silhouetting three figures below the curve of a jagged cliff. The girls clambered over rocks and splashed bare-foot into shallow pools. Their guardian sat bull-necked and proud, scrawling long sentences in a leather-bound notebook.

We let the day fall apart around us, reading passages from her journey, watching the dead at play. A minister approached and held her in conversation for what could have been hours, reflecting on the energy of youth, the beauty of space and the brutality of time. Their laughter blustered on the warm wind and echoed along the coast, swept away by the barrelling waves.

Chloe read: “What is there in humanity, certainly in youthful humanity, that if it can attain its end in two ways, one quiet and decorous, the other difficult and dangerous, it is certain to choose the latter?”

I didn’t know.

She turned the page and went on.

*

A breath of moonlight spilled in a milky stream between the muslin curtains, clarifying the details of our close, musky room: piles of half-finished knitwear, hardback volumes of Walter Scott, broken pencils. I abandoned a dream, on loop, of East End gangster films and took in the view from the window. A lone figure rocked back and forth to the beat of the luminous sea.

I crept from the chamber, down the stairs and out into the garden, stumbling over a serpentine style to the seafront. I broke the latch on a hut at the far end of the bay and dragged a wooden canoe onto the sand. The water rippled about my legs as I pushed the boat into the moon’s fluorescent path – Dinah waiting at the world’s edge.

We danced for hours on the still, sparkling water, lunging into the night and laughing like children. In time, the ghost drew me to the mouth of a gaping cave, where she paused and smiled, before disappearing into the sloshing abyss. I took a deep, dizzying breath and paddled after her, towards the dark and on to the light.

”

”

I disagree, read https://www.stio.com/blogs/news/trek-the-crest

Friendly, Jamika