You have no items in your cart. Want to get some nice things?

Go shopping

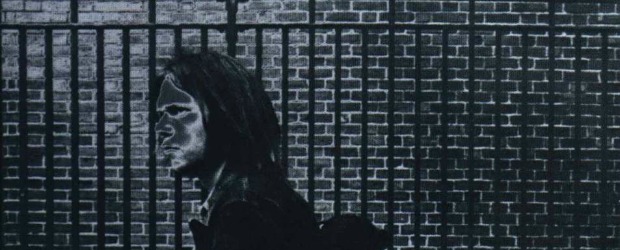

I am sitting on the floor by the record player, trying to select a track from an LP. Minutes have elapsed as I’ve tried to tee up the stylus to land exactly on the quiet part of the record between the ending of one track and the beginning of the next. I raise my eyes to stare at a blank space on the wall and wonder what this part of the record is called, and whether it could be said to belong more to the preceding or the subsequent track. I’m convinced the thing must have a name, but I accept, at this point in the evening, this word is destined to elude me.

I don’t remember when we took the last of the pills, but I checked all my pockets and my wallet and I definitely don’t have any more, so now we’re back at my house to drink some beer, Jen and me. From the living room I can see her in the kitchen mustering the willpower to yank open the fridge door.

“There should be a few bottles of Budvar in there somewhere,” I say.

Jen leans against the fridge, like the knowledge of the effort required to break the rubber seal on the door is a burden to her. She turns to me. “What’re you putting on?”

“Do you like Neil Young?”

“I think we did him in a philosophy lecture.”

“Neil Young? The singer?”

“Maybe it was someone else? I think his name was Young though. Whoever it was, he invented the ‘collective unconscious’?”

“The what?”

“I dunno exactly. It’s about how all of us, whatever background or culture we’re from, dream the same kind of dreams. The same kind of images recur. It means that we’ve all got this thing in common. We’re connected by these images. Archetypes, that’s what they’re called.” She looks over at me, like it is my turn to say something. I’m trying to think about what she’s said, but I’m not sure I’ve completely got hold of it. “So, it’s a nice theory. That we’re all linked.”

“Yeah. That is nice,” I say. And it does sound nice, but at the same time I can’t quite take it on board. It isn’t the time to be wrestling with profundity.

She heaves and the door swings open to the clinking and tinkling of glass. Her smooth legs and bare feet are washed in the fridge’s sickly white light. She starts to nod her head, her mind latching on to the sound of the glass jars and bottles and the rhythmic electrical hum of the fridge motor, as if this music is real. She stops and looks at her feet. “Do you know what happened to my trainers?”

“What do they look like?”

“Dunlop Green Flash.”

“When did you last see them?”

“I don’t know, I was wearing them when I got to the club, I think.”

“They don’t let you in without shoes. Not even girls can get in without shoes.”

“Did I have them when I came out of the club?”

“Dunno.”

I gaze at the blank stretch of wall and try to piece the night together. I met Jerry after work and we went for a few beers in The Victoria, then we hit some bars around town, just going from one to another, trying to find one that we even vaguely liked or in which we felt comfortable, or like we belonged. That must have been when we started drinking shots. Then we took some of the pills I’d bought earlier that day, which I was supposed to be saving to sell to Jerry’s mates at university. Then we went to The Underground. That was where I met Jen. She asked me if I knew where she could get pills. I sorted her out and we got talking. She was easy to talk to. Then again, the way I was feeling I would have found Helen Keller a good conversationalist. I don’t remember what we talked about. We got a cab back to Jerry’s house and he passed out after a bong. I borrowed his car to drive back to my house, with Jen, for beers. I remembered driving Jerry’s old Golf and feeling totally at one with the car, like my heart and lungs were under the bonnet.

“You must have left them at Jerry’s,” I say.

“Jerry’s?”

“The bong casualty.”

“Bollocks,” says Jen, in a way that makes me think she must do this kind of thing all the time.

Jen finds the bottles of Budvar and lifts them out, bumping the fridge door closed with her hip. Her motor skills don’t seem to be functioning very well as she tries to use the bottle opener, experimenting with it, this way and that, in endlessly confounding permutations, before the top finally pops off with a gasp. She pops the second bottle top without any trouble.

I turn back to the record player. My hands can’t make the tiny, refined movements that are required for the delicate procedure of lifting the stylus into place. My brain is still wired up to a different location and a different set of circumstances.

Jen joins me on the floor by the record player. We clink and drink from the bottles. I push the arm on the record player and the needle drops to the vinyl, missing the opening bars and skipping straight into the first verse of ‘After the Gold Rush’.

“I know this,” says Jen. “My boyfriend likes this.”

So, she has a boyfriend. At least he has decent taste in music. I look at Jen watching the record revolving on the turntable and wonder what she looks like with no clothes on. This thought goes as quickly as it had come. We don’t say anything for a while.

“Did I not say I had a boyfriend?”

“You skipped that,” I say.

Jen shrugs. It isn’t clear to me what the shrug might mean. If it is a meaningful shrug at all. For a while neither of us says anything, then she says, “Do you ever do things that you know are wrong but you do them anyway?”

“Doesn’t everyone?” I’m aware this conversation could lead in a number of directions, or nowhere much at all.

“I don’t know. I’m not sure I know why other people act the way they do. Do you?” Her eyes drift in thought, head cocked. I just watch her and we both seem stuck in a moment. “Where did I leave my trainers?” And the moment is over.

“Jerry’s. Remember?”

“Oh, yeah.”

“We’ll drive back over there. I’ll have to give Jerry his car back anyway.”

We fall asleep, curled up on the sofa, listening to records. Nothing happens and when we wake a few hours later it is mid-morning.

“Best get back to Jerry’s and find your trainers,” I say.

It has been a cold night and now it’s started to rain. It is a special Sunday morning sort of rain, the kind that washes away colours and makes everything feel second-hand and shitty. I lend Jen a pair of wellies. They look good on her.

The wipers on Jerry’s car give a squeak on each journey across the windowpane. As a boy, sitting with my mum on draughty buses, I was transfixed by the windscreen wipers. In my childish imagination they seemed like two prize fighters perpetually sizing each other up, without ever coming to blows.

At Jerry’s house he is watching Taxi Driver for the umpteenth time. It’s his favourite film. He does a very good Travis Bickle, if you’ve not heard it a thousand times already. Jen hasn’t heard his Bickle before and laughs. Really laughs; bent over double and clutching her sides laughter. It dawns on me how attractive she is, and I wish she didn’t have a boyfriend and that our night together had turned out differently. We look everywhere, but we can’t find the trainers, so I tell her she can keep the wellies and I’ll drive her home.

She lives on the other side of town and we have to take the ring road, passing all the new boxy retail developments, whose car parks are in permanent flux between being full and empty, without ever quite attaining either state. I start to feel very down. I wonder whether depression is caused by an absence of good, healthy feelings, or a surfeit of dark, unpleasant ones.

I notice the atmosphere in the car has changed too. It’s as if each of us is aware that our time together is nearly over and whatever connection we might have had is withering, and will soon be severed entirely. It’s a weird feeling, and I wonder if she really is feeling like this too, or if that’s just how I’d like her to be feeling.

Jen’s checking her eyes in the vanity mirror. Her pupils are still dilated and she’s got that blank, pillhead look about her. I massage my jaw, the skin rubbery and alien.

She asks me to drop her off at the corner of her street and there’s an awkward moment, punctuated by the squeak of the wiper blades, where we’re not sure what the situation is calling for: a kiss, a hug, a handshake, or some words? What words?

“You better have these back,” Jen tries to slip off the wellies, but they’re stuck. She tugs at them, yanking her foot up over the dashboard, slumping low into her seat.

“Have them,” I say.

“Thanks,” she says and touches my hand which is resting on the gear stick. “See ya.”

“See ya.”

I watch her running through the rain in my wellies and wonder again what she might look like naked. Suddenly, she’s rushing back toward the car, jerking the door open.

“Karl Jung!”

“Eh?”

“Karl Jung!” she says. “The collective unconscious! Remember?”

“I had a feeling it wasn’t Neil Young,” I say.

We shrug at each other and then she’s off again, her wellies making indistinct footprints on the tarmac for an instant before the rain washes them away. And she’s gone. I put the car in gear and head back out into the teeming ring road traffic.

Jerry quizzes me about Jen and what happened. When he asks why I didn’t sleep with her I tell him that she has a boyfriend and Jerry gives me a look. I’m not sure why I didn’t sleep with her when I had the chance, but somehow I’m glad that I didn’t. I don’t tell Jerry this.

He drops me off at my house and I get a bottle of Budvar from the fridge. I cue up a record and sit down on the sofa, casting my eyes around the room. In the corner, by the television, are Jen’s Dunlop Green Flash, heels together, toes touching the skirting board. There’s the sound of the needle hitting and riding over the grooves of the vinyl for a second or two, then the plaintive piano intro of ‘After the Gold Rush’ comes over the speakers. I take a drink and for a moment I’m thinking about the end of things; how certain things come to an end and how new things begin. Endlessly. I can’t hold on to the thought though, and soon I’m thinking about something else, something different.

About GC Perry

GC Perry has a number of stories in the Litro archive and has also appeared in Strix, Liars' League, Shooter, Open Pen, Prole and elsewhere. His flash and microfictions have been shortlisted for the Fish and NFFD prizes. He lives in London.