You have no items in your cart. Want to get some nice things?

Go shopping

When news that cyclist Lance Armstrong had, in fact, lied about doping during his acquisition of professional cycling titles, it wasn’t just news. It was breaking news, each new development was front page, and he was the subject of talk in offices and over family breakfast tables the world over. His story pushed other news articles to the margins. The world didn’t want to hear about Syrian refugees, or government spending cuts, or terrible flooding. The world wanted to know how it was that a man who said he did not cheat, could in fact, have actually cheated. It seemed so impossible that a person, an actual human person, could lie about something like cheating. So impossible, that the world needed Lance to have a special interview with Oprah Winfrey, where he could really get all the truth out, all the truth that had been so clearly tearing away at him for all these years.

After the revelations, people started to get angry. Lance had sold books, that weren’t just books, but memoirs, and told people they were true. He overcame cancer and won all those cycling titles by himself, no doping required. He was an inspiration. The moment inaccuracies in his accounts are discovered, his memoirs are no longer inspirational. All the people who had been inspired wanted their money back, for how could they continue to be inspired by a lie?

Why it is so inconceivable to us that there may be inaccuracies in memoirs or autobiographies? These works are rooted in the memories of the writers behind the words, and don’t we all know that nothing is as unreliable as memory? Memory, surely, is always reconstructive. You’re always trying to get at some approximation of what went on rather than an exact recording of an event:

“Our memories are filled with gaps and distortions, because by its very nature memory is selective.” (Patrick Duff, From the Brink of Oblivion).

Really, what I want to talk about is truth. Everyone has their own meaning and interpretation of it. It’s not for me to say who or what or why or where truth is, but I want to explore our reaction to it. How we respond to truths that we are presented with and how we engage with them, especially in terms of the context in which they are presented to us. Why is it that we are so stung when it is discovered that what we have been told is truth is in fact lie? Conversely, why do we willingly watch, read and engage with fictions and fantasies we know to be untrue, not real and yet that we find emotional truth in?

In 1938, the story goes, a radio adaptation of H.G.Well’s War of the Worlds read by Orson Wells had people believing, really truly believing, that there was an alien invasion taking place on Earth. It turns out that people probably in fact realized it was what it was, and didn’t descend to panic and terror. It was, instead, a media myth. But our willingness to believe this story; i.e. the story of people believing anything, is perhaps more interesting. We believe quite readily that its possible for people – people like ourselves – to be convinced of a lie. But when it’s us personally who have been had by some hoax or con, we become indignant. We refute the fact that we could have been conned so easily.

In the case of Lance Armstrong, he is being sued for fraud and false advertising amid claims his inspirational books are full of lies. This isn’t the first time a memoir has caused uproar by not being as truthful as people wanted to believe. Think James Frey’s Million Little Pieces. Like Armstrong, he too had to come and make his apologies and unreserved confessions to the almighty Oprah. This wasn’t enough, for there was the matter of money, of course –

“In the aftermath of the Million Little Pieces outrage, Random House reached a tentative settlement with readers who felt defrauded by Frey. To receive a refund, hoodwinked customers had to mail in a piece of the book […] those with paperback copies were required to actually tear off the front cover and send it in. Also, readers had to sign a sworn statement confirming that they had bought the book with the belief it was a real memoir, or, in other words, that they felt bad having accidentally read a novel.” (David Shields)

It troubles me that even though people become so incensed by what they see as inaccuracies purporting to be accuracies, lies purporting to be truths, that there are still memoir fictions on every shelf in all the big mega-stores, and people continue to read and believe them.

David Shields notes that “For centuries, the memoir was, by definition: prayerful entreaty and inventory of sins.” It’s this “inventory of sins” that is a little concerning, perhaps. Because it attaches to the memoir genre a kind of voyeurism, a peeping Tom characteristic of wanting to see a person’s dirty secrets. Rather than looking for quality of writing or sentiment or meaning, the act of reading a memoir becomes rather more intrusive, bordering on trespassing on a person’s private affairs.

This, surely, does not give the right to demand accuracies in a person’s memoirs. In the same way as a trespasser wouldn’t demand doors kept unlocked, a reader of memoir has no ground to demand every single truth and detail of another person’s thoughts, actions and past experiences. Not only are these things subject to memory failings, they are also intrinsically a person’s story – told selectively in the way they wish.

Perhaps, we should expect there to be inaccuracies in works so firmly rooted in personal memories. We know human beings can be deceived. We even kind of like the idea, as long as it doesn’t happen to us. If we continue reading and buying people’s memories in their packaged forms, perhaps we should be reminded that memories aren’t the same as the truth. After all, we are reminded on most every novel we pick up that the words we are about to read are fiction and that ‘any similarities between real life events or real people’ is wholly unintentional. There’s no heartbreak in reading fiction. People are happy to enter into an agreement. We all understand that what we are reading may not have actually happened.

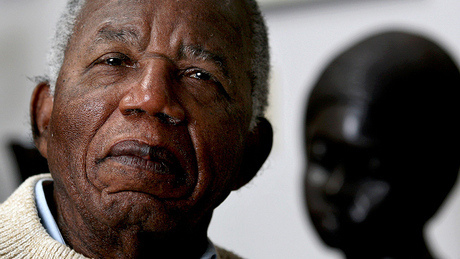

But do factual inaccuracies even matter? The great Nigerian writer, Chinua Achebe wrote, “all stories are true.” This idea is rooted in experiences and emotions that are shared throughout humanity. In so many stories, the key isn’t what is real and what isn’t, but rather descriptions of lived experiences that feel true because we recgonise them. In writing, the use of small, exact, concrete detail can be set beside scenes and so focus on clear moments of dramatic detail to create a real sense of lived experience and risk that feels very true to the senses. In the act of reading and seeing the scenes described, our human senses fill out the rest and make it believable. It doesn’t matter if the stories and scenes are true or not; the impressions and the feelings we have remain. Those feelings and impressions are true and real, because we know without doubt that we truly did feel that way.

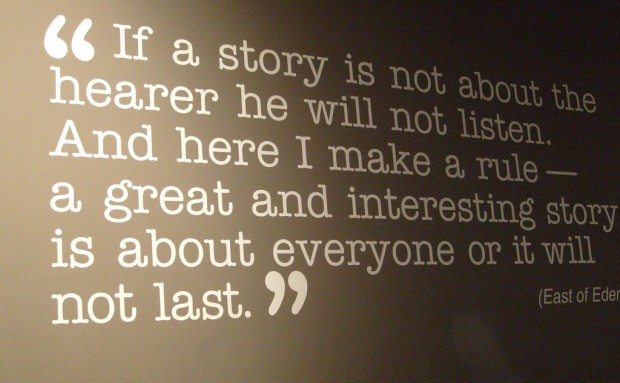

Part of what writing and reading is about is finding connections. Story telling was once predicated on physical connection between humans, the oral tradition of telling stories to one another around a fire. Now, connections are found through recognizing truth veiled by syntax and grammar and language. What lays under the surface are the feelings that we share. We find truth in writing because ultimately it is communication. When we truly listen to each other, we find this sense of shared connectivity. Because at the deepest of levels we are all the same, we find solace in the same things, find truth and meaning in the same things. We are biologically wired to want to communicate, and yet we can’t just rely on news and facts and reportage to satisfy our needs of communication. Gossip magazines and the news – so inevitably about “power and sports and anger and death” (Kurt Vonnegut, Slaughterhouse 5) will only go so far. We need other forms that connect us.

As things stand, our culture is becoming more and more concerned with a strange fetishisation of truth and memory and hard fact, rather than being open to other possibilities, other truths, other realities. As Japanese writer Haruki Murikami says of his own writing “I want [it] to be open to all the possibilities of the world.”

This isn’t to say that memoirs are not good stories. If there’s something to it that we recognize in ourselves, then there’s an emotive truth there that is real. But we don’t necessarily need memoirs and inside scoops on people’s private lives and personal histories. If we want a story because it connects with us in some way, then turn to classic works of literature, for here inspirational stories abound. Or to new and emerging writers and artists that are trying to emulate the classics in their own unique way and are creating new perceptions of truths, new realizations of lived experience, and who are trying to do what man has always been trying to do: communicate with other humans and bring us together through stories.

About Samuel Dodson

Samuel Dodson is an award-winning writer and editor based in London, UK. A graduate (BA and MA) of the Warwick University Writing Programme, he has appeared on the BBC and LBC, and is the founder of Nothing in the Rulebook – an international collective of writers and artists. His first book, ‘Philosophers’ Dogs’, will be published by Unbound in 2021.

- Web |

- More Posts(4)