You have no items in your cart. Want to get some nice things?

Go shoppingI need to start with a disclaimer: there are a lot of Dicks in this book. There are also lots of long and often obscure words. But while I’m keeping the dicks in my review to a minimum, the words are harder to translate. In fact, you may find them a bit of a mouthful, but you only have your Self to blame. So if you read this and get your haecceity confused with your quiddity, as I’ll do in a bit, don’t worry. I’m just easing you into some of the language of the novel. It’s all part of the fun—and after all, isn’t it Will Self’s own stated aim “to be misunderstood”?

Like many of you, I’ve wondered Whatever Happened to Corey Haim, gone Desperately Seeking Julio (the available translation of Maruja Torres’ Oh es él! Viaje fantástico hacia Julio Iglesias, though you would be mad not to prefer the more literal Oh it’s him! Fantastic voyage to Julio Inglesias) and thought about Being John Malkovich.

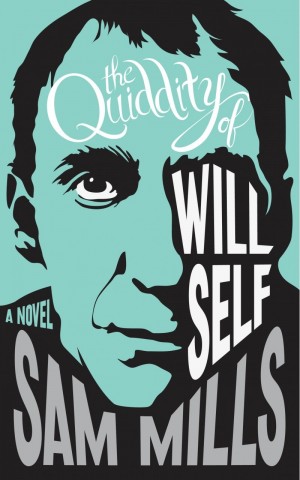

The Quiddity of Will Self, according to its author Sam Mills, is the “literary equivalent” of Malkovich—or BJM, as it’s called in the novel. At first, I had difficulty with this concept. After all, one of the main reasons the film works is that Malkovich is in it. He’s there on the screen in front of you, quite literally being John Malkovich. How do you replicate that in literature? You can take an author (as Mills has), you can write like them (as Mills sometimes does), you can put them into your novel as a character (as Mills has), but you can’t ever really be them. Short of Self writing about himself, as he’s already done in Walking to Hollywood, the same idea doesn’t easily translate from screen to page.

The other difficulty I had is that quiddity, the concept central to Mills’ novel, is all about a thing’s “whatness”. Not what makes it unique, which is haecceity or “thisness”, but what properties it shares with others. Often, though, Mills’ fictional quiddity seems more like haecceity. Her book is written in the style of the idea of Will Self: long words and lots of cocks. Characters in The Quiddity of Will Self form a cult to worship the Self, and there is even a drug that allows them to share perspective as the Self. Substance abuse theory aside, if I wanted to get at the whatness or thisness of Will Self, why not just read his books instead?

Which is harsh. The Quiddity of Will Self is perhaps flawed, but it’s also a great and very ambitious book, and it needs to be accepted for what it is. You can enjoy the ideas, the invention, and the constant confusion of fact, fiction and authorship—one reviewer got the author’s gender wrong, not so strange when you consider that the fictional version of Sam Mills is male in part five of the novel—but if you’re looking for a sympathetic narrator, you’re unlikely to find one here.

The book is divided into five sections of varying style, quality and length. Despite having one of my favourite opening lines ever, the first section of the book is much too long. It has more than a whiff of Self’s novella, The Sweet Smell of Psychosis, in which a journalist called Richard falls into the orbit of media monster Bell and his cronies. In Quiddity’s first part, a writer (another Dick) falls in with the inner literary circle of the Will Self Club after his mixed-up downstairs neighbour, who has had plastic surgery so that she resembles Will Self, is found murdered. The victim, Sylvie, returns in part two, this time as a ghost who haunts Self’s study whilst the writer works obliviously. Part three continues the tale of Richard, who has been framed for Sylvie’s murder, as he participates in a New Deal Reintegration program run by Professor Self (no relation) as an alternative to prison, and part four is set in a 2049 where Will Self has finally won the Booker Prize, aged 82.

However, it is part five where the book comes into its own. We are introduced to the narrator Sam Mills, as he (yes, he) tries to get The Quiddity of Will Self published, fails to meet Will Self, and founds the Will Self Club. There’s quite a lot of BJM too. This witty, semi self-referential section really works, and made me forgive some of the weaker parts of the novel as they’re necessary as precursors for this last and strongest section. According to both the fictional Sam Mills in the book and the author in an interview, The Quiddity of Will Self took nine years to write. As a novel it’s perhaps too long and disjointed, but as a set of linked stories (much like Self’s debut The Quantity Theory of Insanity) it stands up, and the final section flies. It is weakest where it feels like the author has written part of it, put it down, and then returned quite a while later with a new idea, but that’s a small price to pay because the ideas themselves are worth it.

As Sam’s fictional agent Archie tells him (with a nod to her real agent, Simon Trewin), “We’re in a recession and everyone is cautious.” Fortunately, though, they weren’t too cautious to publish this strange and original book. Whatever its shortcomings, it remains very much my idea of fun.

About Giles Anderson

Giles Anderson grew up in a variety of boarding houses on the south coast of England where he learnt to write about himself in the third person. For many of his formative years his parents continued to dress him in boiler suits and Wellington boots such that he is most at home in the company of tradesmen and Bond film henchmen. He holds Bachelor degrees in War Studies and Law and a Masters in Medieval Studies, any of which is more than outweighed by his failure to complete several novels, a PhD in medieval cartography, Masters degrees in Egyptology and Victorian Studies and Bar Finals. With his educational background it was obviously a natural step to work as a bookkeeper for a rope importer, then for the now defunct Medicine Control Agency, before racing into the near present as an employee, then Director of a photographic press agency. Such is his love of images that he decided to devote himself entirely to words. Whilst a picture may paint a thousand words, that doesn’t mean ninety of them make a novel (or a small art gallery if you’re Proust).