You have no items in your cart. Want to get some nice things?

Go shopping

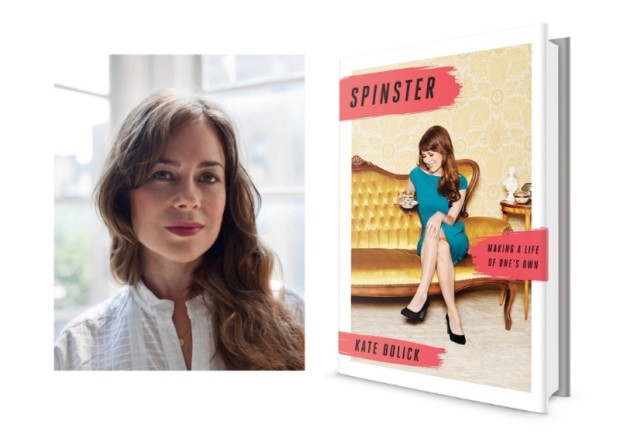

What a difference seven years can make. Kate Bolick, author of the well-reviewed and much-discussed Spinster: Making a Life of One’s Own, which traces her life as a young professional writer dodging the marriage bullet, graduated from high school in 1990. My voyage from high school to university at the age of 17 was in 1983. Those transitional years between the mid-eighties and the early nineties mark a period of shifting ground when Second Wave Feminism crashed loudly into the unsettled waters of the Third Wave. During these years the emphasis in the feminist movement was shifting from the collective to the individual, and from the political to the personal—and not coincidentally these changes occurred simultaneously with the rapid growth of Reagan-Thatcher capitalism and its emphasis on individual choice and consumption.

The portrait of the society Bolick inhabits—a society, which by her account, is populated by women who are all busily dreaming of marriage is not one I recognise. She speaks for all women in the opening sentence of Spinster in what I can only assume is an attempt at Austenesque irony: “Whom to marry, and when will it happen—these two questions define every woman’s existence.” The use of “every woman” here, which is repeated throughout the book, only serves to alienate those of us who actually took on board the literature, the academic probing, the arguments and discussions from the Suffragettes to the feminists of the sixties and seventies and beyond as we navigated our way through the world as young women. “Though marriage was no longer compulsory, the way it had been in the 1950s,” Bolick writes, “we continued to organize our lives around it, unchallenged.” We? Unchallenged? Really? What a difference those seven years made.

Towards the very end of the book, Bolick shifts into a more personal gear when she asserts that “the question I’d long posed to myself—whether to be married or to be single—is a false binary. The space in which I’ve always wanted to live—indeed, where I have spent my adulthood—isn’t between these two poles, but beyond it. The choice between being married versus being single doesn’t even belong here in the twenty-first century.” Exactly. That choice doesn’t belong in the 21st century because it was debated at length by the likes of Mary Wollstonecraft and John Stuart Mill, Simone de Beauvoir, bell hooks, Adrienne Rich, Betty Friedan, Germaine Greer, and countless intellectuals and writers. Even the early feminist Lady Mary Chudleigh (1656-1710) famously made the connection between patriarchy and marriage when she wrote: “Wife and servant are the same, but only differ in the name.” That was in 1705.

Where Bolick had always dreamed of marriage – “But of course I wanted to be married. In college I’d decided I’d marry by thirty” – my friends and I were dreaming of love and sex. Marriage was seen as the unnecessary packaging destined to be thrown into the metaphorical feminist landfill site along with chastity belts, foot bindings, and corsets. Marriage was love wrapped up in the bells and whistles of capitalism and the conventionally accepted narrative of a woman’s life—the very things we were fighting against. Not for us the virginal white dress, the changing of our surname, the ‘giving away’ of the bride by her father (oh, the awful symbolism in this gesture) and the vows of servitude and obedience. Unlike Bolick’s friends, we wanted none of it. Apparently in Bolick’s social circle, not to get married required “a very good explanation” – which, she adds, “I certainly didn’t have”. What about the wealth of feminist thought, argument, literature and essays for furnishing those pesky explanations? I notice Bolick name checks Simone de Beauvoir in her bibliography without mentioning her once in the text. Surely a few lines from The Second Sex could provide Bolick with the elusive excuses she and her friends need to justify their desire to not tie the knot?

The title of Bolick’s book set up for me the expectation of a historical overview of the single, unmarried woman: the fictional heroine from Brian Moore’s eponymous book, The Lonely Passion of Judith Hearne, perhaps. Or Henry James’s construction of spinsterhood in the form of Olive Chancellor in The Bostonians. Or maybe the real Salem Witches and their foremothers. Bolick does mention Henry James’s Isabel Archer and Daisy Miller without noting that neither of them were actually spinsters. But who cares! For Bolick the term “spinster” is so elastic that it loses all meaning: “For the happily coupled, particularly those balancing work and children, spinster can be code for remembering to take time out for yourself.” Code? What does that even mean?

For anyone who cares about language, and I put people who write books into this category, it is an irrefutable fact that the definition and etymology of words are paramount. If a writer uses “dyke” or “queer” or “spinster”, they do so with the responsibility that comes with communicating with a reader. But in Bolick-land, who has time for semantics when you have a book to sell? Real life spinster writers don’t get a mention in the book. There is no Jane Austen, Louisa May Alcott, Flannery O’Connor, Maria Edgeworth, or Christina Rosetti, nor do we find any of the writers who challenged marriage and forged new lives as independent women like George Eliot and Mary Wollstonecraft. What we get instead are lightly drawn portraits of five women whom Bolick calls her “Awakeners” (without so much as a nod to Kate Chopin’s 1899 proto-feminist novel, The Awakening. Chopin’s seminal work isn’t even listed in the bibliography).

Out of Bolick’s five spinster “Awakeners”, only one of them, Edna St. Vincent Millay, was actually a spinster. Neith Boyce was married with four children. Maeve Brennan (Bolick’s “patron saint” of spinsterhood) had been married, as was Edith Wharton. Charlotte Perkins Gilman was married with a daughter. But none of this matters to Bolick. The fact that the word has a history and a meaning is irrelevant—another symptom of the strange ahistoricism at the heart of this book. Bolick flounces through the lists of boyfriends and suitors who can’t help but offer her a brownstone if only she’ll marry them, or the lovely men who want so much to be with her, but from whom she needs her space. This is not spinsterhood. This is called making a choice. To remain unmarried as a personal decision is not the same as having it thrust upon you. And despite the fact that Bolick thinks that being unmarried is a brave move on her part, it is simply the result of the political actions and sacrifices of the women who came before her, whom she doesn’t care to mention. To choose not to marry in the 17th, 18th, or 19th centuries was brave; to do so now is simply acting upon one of many choices available to women. Bolick manages to drain any political discussion from the subject of women as spinsters, which is a shame, especially as the book came out a month before same-sex marriage was made legal in Ireland, and two months before it became legal nationwide in the U.S. A time when men and women are seeing a new freedom in whom they choose to make a life with—or not. Bolick’s assertion that all women dream of marriage is anachronistic.

There is an important subject to be probed here, one brought up by de Beauvoir in 1949 when she wrote: “Man is defined as a human being and a woman as a female.” One could add to this the age-old adage that bachelors are always seen as “swinging” while spinsters are seen as “sad”. There is much more to be said on this matter in the early 21st century, but Bolick with her inability to place herself in the context of this ongoing discussion is not the person for the job.

Kate Bolick’s Spinster: Making a Life of One’s Own is published by Crown Publishing Group.

About Joanna Pocock

Joanna Pocock graduated with distinction from the Creative Writing MA at Bath Spa University. She is a contributing travel writer for The LA Times, and has had work published in The Nation, Orion, JSTOR Daily, Distinctly Montana, the London Sunday Independent, 3:AM, Mslexia, the Dark Mountain blog and Good Housekeeping, among other publications. In 2017 she was shortlisted for the Barry Lopez Creative Non-fiction Prize and in 2018 she won the Fitzcarraldo Editions Essay Prize. 'Surrender', her book about rewilders, nomads and ecosexuals in the American West, will be published by Fitzcarraldo in 2019. She teaches Creative Writing, both fiction and non-fiction, at Central St Martins in London. Some of her writing can be found at: www.joannapocock.blogspot.co.uk and www.missoulabound.worpress.com

Good Post of Nice Information

Thank you!

Thanks for this amazing post dear.